![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Good Will Brewing

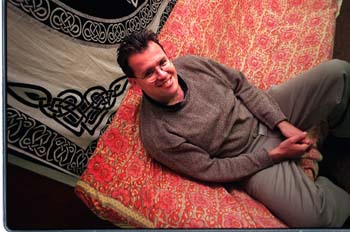

Hangin' with the Lord: Living Room founder Robert Strickland offers a safe place for homeless youth. But instead of preaching, he lets the good work speak for itself.

A new brand of street mission for homeless young people, the Living Room's free coffee shop finds that, instead of prayer, just being there is as good as Gospel

By Mary Spicuzza

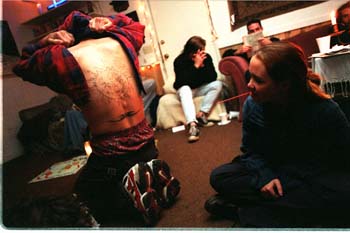

JULIE CRADLES a cup of hot chocolate in her small hands, her thin fingers covered with silver rings. She leans forward, warming her flushed face with wisps of steam. Even with a thick knit cap pulled down to just over her deep blue eyes, Julie's square jaw and striking black hair show that, at only 16 years old, the aspiring model is already quite beautiful.

When I mention a local modeling school, Julie glances over excitedly at her friend Klepto, who, toothbrush in hand, is busily organizing his backpack. But her face darkens quickly.

"You need parental consent for that, don't you?" she asks coldly.

Julie has been homeless for four years. She last saw her mother shortly after her 12th birthday.

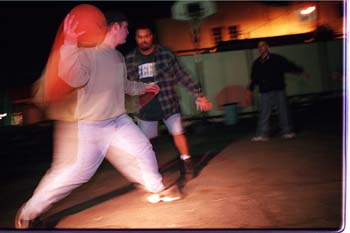

Nearby, Robyn and Albert sink down into one of the coffee shop's soft couches, out of breath from a game of basketball on the Elm Street Mission's small court. Julie hops up to give Albert a hug, and within minutes he's teasing her like an older brother.

As she spins on her heels and nestles back into her spot next to Klepto, Robyn explains that he's known Julie since he spent six months on the streets a couple of years back. He says that he knew she left home because her mom's boyfriend was abusing her, but he didn't know how he could help. Robyn, now 23 years old and living in Santa Cruz's Clean & Sober House, used to spend some nights in shelters, others at the Santa Cruz armory.

No shelters in Santa Cruz County accept homeless children without their parents. For Julie and the other 1.3 million unattached homeless teens in the country, parental consent doesn't come easy.

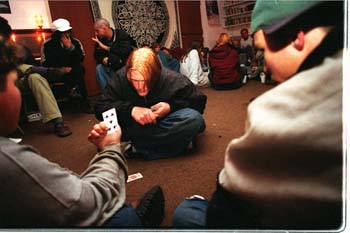

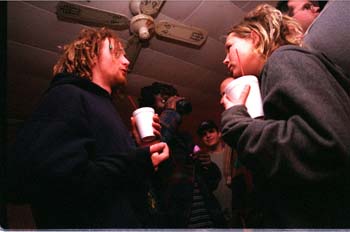

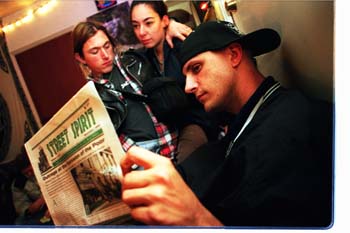

Robyn leans forward in his seat and surveys the Friday night crowd at the Living Room, known to most kids on the streets as "the Christian coffee shop" or just "coffee shop." Amid flickering white lights, about 40 teenagers hang out in the dimly lit room. Some play board games, others are curled up sleeping. Most just sip coffee, munch cookies and talk with friends.

There's little that separates the Christian coffee-shop ministry run out of downtown's Elm Street Mission from any of the other countless java joints in town--except everything's free, the music is all contemporary Christian rock and a few note cards scattered on the tables hold reminders like "The Lord Loves You" and "The Lord Keeps You Safe."

The Elm Street Mission, tucked between Pacific Avenue's Streetlight Records and Caffe Pergolesi on Cedar Street, was built in the mid-19th century and has been serving the homeless since the late '60s, giving free meals after prayer services on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights. The mission offers Bible study, services in Spanish and a Jewish-Christian fellowship. It also opens its facilities to certain ministry projects.

The coffee shop is one of those projects. Nearly two years old, the Living Room is open to anyone under 25 looking for a place that's warm and dry--and clean and sober--to hang out with friends. Rather than requiring prayer or gospel readings, its founder, Robert Strickland, hopes the unique ministry can show "the love of God"--teaching through example instead of preaching.

"I don't know a lot of the younger kids," Robyn frowns, surveying the room. "It's like there's a whole new generation of street kids out there."

Looking around the room, I notice at least a handful of kids who look barely old enough for Little League.

In the far corner, three young men are leaning intently over a Monopoly board. When I ask who's winning, their friend Shay points at the owner of the most expensive properties, Boardwalk and Park Place. The player grins proudly at his properties, and the two small plastic houses on each blue square, as he collects another rent payment.

Shay sighs, "See? You gotta have houses to win."

Finding Help: Services available to homeless youth.

New Wave Religion

WITHIN THE FIRST five minutes of explaining how his unique coffee shop came to be, Robert Strickland has already mentioned both the Cure and Siouxsie and the Banshees. Quoting periodically from the '80s band Echo and the Bunnymen, the Gospel and Good Will Hunting, he is clearly not your old-school missionary.

With his short hair, cleanshaven face, straight good looks and cozy knit sweater, Strickland looks like he could be on his way to a photo shoot for the Gap Christmas catalog. But as he tells stories about his late teens, scenes from Trainspotting come to mind.

Strickland, 29, grew up in a middle-class neighborhood of Gilroy, the youngest son in a traditional Catholic family. As a teenager, he found an escape from boredom in New Wave and the San Francisco club scene. Strickland says clubbing was first a way to hang out with friends and meet people his own age but quickly became centered around abusing drugs and alcohol.

"It wasn't a drug dealer on a corner who got me hooked," Strickland says. "It was close friends who introduced me to cocaine."

Not all homeless young people are using drugs, but like the parties of teens living in stable homes or college dormitories, street social circles often revolve around partying where drugs are available.

"It's crazy out there," coffee-shop patron Dragonfly says. He leans back, propping up his feet on a small end table. "This is my weekend getaway."

Dragonfly, who's been going to the Living Room for several months, says he finally has somewhere to go on the weekends that's not about doing drugs and staying up all night.

Strickland is familiar with the pressures of party scenes. He watched his best friend, Nick, die of AIDS at age 24. Nick had been shooting heroin for years, and Strickland believes he contracted the disease either from dirty needles or during his years as a prostitute.

Another friend, Kristin, had just gotten out of the hospital after an overdose the last time Strickland talked to her. Kristen's boyfriend was pimping her to make rent and buy heroin. He believes she's still alive but thinks that years of addiction are strangling her soul.

"I liken it to being in a car wreck," Strickland says. He looks down into the cream swirling in his coffee. "And I walked away from it."

Rebounding from drugs is a common thread in born-again missions, and Strickland acknowledges that his past struggles with addiction shaped his youth outreach efforts. During a bad acid trip, he stayed up all night "frying," calling countless drug-treatment centers looking for help. He was in a rehabilitation center by the time he turned 20.

"I didn't think I was going to make it out. I remember seeing people consumed with that life ... seeing how drugs and alcohol change people to the point where friends and family don't recognize them anymore," Strickland recalls. "I said to myself--and God if He was there--that if I get out I want to help someone else."

Court in Session: Ross Morales, Robyn Gatchell and "T-Bone" play basketball at the hoop outside the Living Room coffee shop.

Home Fire

CONVERSION TALES--and their skeptics--aren't hard to come by. Everyone from soldiers in the trenches to prisoners, prostitutes and Hell's Angels have found God and been "saved." The most vulnerable lost souls often become the most devout in their faith. Believers call it salvation.

Strickland is well aware of the stereotypes around street missions--that they prey on the needy and desperate--but insists he found God on his own without pressure or indoctrination. He'd rather show God's love through kind actions than by preaching about it.

"I had a spiritual experience and found God as I understand Him to be. It was a One-on-one in rehab; nobody else was there," Strickland insists. "A lot of times people think you get sucked into these religions at an impressionable stage. But I really came to my own conclusions. It was a totally conscious decision."

After rehab, Strickland finished college and got his master of arts degree in theology from Fuller Theological Seminary. He's been clean and sober for eight years.

"I can't think of a better way to apply my major," he smiles, glancing toward the door. Another teen has just wandered in and signed the guest book, helping himself to a slice of cake. By midnight, the guest book is full, with more than 100 signatures.

Strickland says his struggles to find his own path have shaped the coffee-shop ministry.

For one, he doesn't include a mandatory sermon. No prayer is required at the Living Room. No Gospel reading, not even a moment of silence is asked of anyone throughout the four hours each weekend night that the coffee shop is open.

Ken, who was homeless before becoming one of the handful of live-in volunteers at the mission, remembers one volunteer who insisted on loudly quoting scripture at the coffee shop. After she refused to change her preaching techniques, he says Strickland asked her to leave.

"When I think of her, the image of a Bible thumper definitely comes to mind," Ken shrugs. "Robert believes in bearing silent witness--teaching God's love by showing it."

Strickland bases his anti-preaching stance on his belief that no one will change his life until he wants to, which he acknowledges sometimes means "hitting rock bottom." He remembers growing up resenting those who tried to impose their beliefs on others, especially on kids.

Filling my Styrofoam cup with hot cocoa, I can hear coffee-shop co-founder Christie Keifer and her friend November Belleto talking about the power of God. They decided to get involved after reading about tales of the Jesus Movement of the 1970s. The two friends moved to Santa Cruz from Southern California three years ago.

The Jesus Movement combined '60s anti-establishment sentiment and an emphasis on social movements with a shared love of the Lord. Their huge gatherings had all of the passion of Hair, but fully clothed and without the free love. They often included Gospel readings and preaching.

Keifer and coffee-shop volunteer Hippie Dan, who preaches at some of the weekend pre-meal prayer services at the Elm Street Mission, agree that Gospel readings isn't what the coffee shop is all about. They see it as more of a timeout from the streets or the pressures of the drug culture.

"I just want to give them a place to come and think. It's more of an intermission," Strickland says. "I'm sensitive to the need to respect individual freedom, and I totally endorse that. Nobody who comes to us is forced to change their belief system."

Words like "totally," "awesome" and "dude" come up regularly throughout our interview. But unlike an out-of-touch outsider using teen words to convince himself he's still cool, he sounds more like he is naturally slipping into his native California speech.

"It's like, 'Here you go. We believe there is a God who loves people, and we're going to do what we can to show good will towards men ... and women," Strickland says. "In terms of indoctrinating people, we absolutely do not do that."

States of Grace

STRICKLAND ADMITS that when I first called, he was leery of doing an interview--apparently afraid of another media hound out for a good local-cult-brainwashes-kids story. Meanwhile, I was curious about what religious outreach methods work with homeless and at-risk teens. Kids on the streets are self-reliant, but they are also vulnerable. Although religion and spirituality can be powerful forces for social change, others have used them to serve their own agendas.

A recent reminder of this was the 20th anniversary of Jonestown, as well as the Concerned Christians group that vanished from Colorado this fall. Members of both groups signed over their assets to their leaders. Images of the Comet Hale-Bopp crowd in Southern California and the Waco compound being consumed by flames still linger from the not-too-distant past.

For each of those stories, though, there are hundreds of churches and congregations involved in social programs. Private nonprofits and religious organizations have historically served as the backbone for homeless programs.

Missionary and outreach approaches vary depending on the congregation. Many mainstream churches tend to focus on social service based on Jesus' example, while more conservative evangelical groups have emphasized saving souls by actively proselytizing.

In stricter fundamentalist groups, the "free" meal often comes at the price of a required sermon, and there's an emphasis on soul salvation. This has drawn criticism from those who feel conservative street missions take a judgmental--and sometimes counterproductive--approach to working with the homeless.

Between 1985 and 1992, anthropologist Michael Robertson spent months living on the streets of Albuquerque, N.M. During that time, he spoke with dozens of fundamentalist and mainstream Christians operating street missions for the homeless. Robertson chronicles his experiences in the book There's No Place Like Home.

He takes issue with the fundamentalists he encountered who viewed the homeless people as struggling with sin and moral flaws.

"The belief that homeless persons have fallen from a perceived higher social status is pervasive. It echoes the biblical theme of Man's Fall from Grace," Robertson writes. "It characterizes homeless persons as sinking to the lower depths of human living and morality." Robertson argues that there are too many factors leading to homelessness to make sweeping character assumptions.

Although Strickland believes that it's irresponsible not to educate kids about the dangers of drug abuse, he avoids moral judgments.

"Addiction is a real thing. It will turn a person into someone they never wanted to be," Strickland says. "I'm not going to say that person is a bad person, but I know a lot of good kids with bad drug problems. I see us less as a homeless program and more of youth outreach for a certain subculture."

Strickland also shuns traditional labels like "fundamentalist," "Catholic" and "evangelical."

"Those labels have so much baggage attached to them," he says. "We're Christians; we include all denominations. And we're open to anyone."

The Living Room is funded solely by private donations, mainly from small, locally owned businesses. Though youth outreach with a religious bent can limit the flow of money, not receiving money from federal agencies brings with it a certain amount of freedom.

"We need to find a local solution to a local problem," Strickland says. "We can't wait for a Big Brother or Big Sister to come in and solve our problems. No one group is going to fix things."

Silent Nights

IN A RECENT EPISODE of pop-culture-infused Buffy the Vampire Slayer, a religious home for homeless runaways turns out to be a front for a demonic operation. The nice preacher basically sucks the life out of teens before spitting them back onto the streets.

Strickland is aware of the suspicions around religious outreach and says he's gotten criticism from all sides. Skeptics accuse street missions of trying to indoctrinate the vulnerable, while some religious outreach programs believe saving souls requires preaching the Gospel.

In Santa Cruz, homeless advocates seem to be less critical of activism with religious roots. Few working in publicly funded outreach for street kids were familiar with the Living Room, but none was against the idea of the coffee-shop ministry.

"To me, whoever wants to do this should do it," says Kimberly Carter, founder of Above the Line. "The more the better. There's no one answer for all homeless kids." Strickland says the coffee shop's strongest advocates are the kids who use the program.

As midnight approaches and the coffee shop prepares to close its doors, the Monopoly board, with its plastic houses and property deeds, has been neatly folded and tucked away.

Dragonfly is curled up in the corner sleeping, his arms wrapped around a small round pillow. He says he prefers camping to shelters, where he's afraid of disease or theft.

But camping has its own downside. Klepto mentions the "bum bashers," drunken guys who beat up the homeless sleeping outside.

Either way, Klepto and Julie don't have the choice. Until Above the Line opens its home for teenagers on Freedom Boulevard early next year, there is nowhere for the area's more than 200 homeless youth to sleep legally in Santa Cruz County.

Strickland admits it's hard sometimes to close shop and send everyone back out into the streets.

"I just hope that someday they will look back and think, 'These people, whether I believe what they believe, cared enough to be there for me,'" he adds. "The way I see it, we're just doing one small part of a big puzzle."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

From the December 17-23, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.