![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Poetic Justice

The state of California has rested on its laureates long enough

By Tai Moses

GOLDEN TROUT, desert tortoise, dog-face butterfly, Charles B. Garrigus--what do these things have in common? They're all official state symbols of California. Although most Californians can name a few of their state insignias--poppy, state flower; redwood, state tree--few are aware that the state has its own poet laureate.

Or had: Charles Garrigus died in October, leaving the post of laureate vacant for the first time in more than three decades.

On Dec. 4, the California state legislature reconvened for its first session since Garrigus' death. The selection of a new laureate rests in the hands of two lawmakers: Senator John Burton, the president pro tem, and Assembly Speaker Robert Hertzberg. How they will fill the vacancy is a subject that has the state's poetic pundits in turmoil.

Garrigus Get Your Gun

GARRIGUS WAS the fifth to wear the crown of California poet laureate. A former Democratic member of the legislature and a poetry buff, Garrigus was granted the mostly ceremonial post by his peers in 1966 (it's a lifetime appointment).

In the 34 years Garrigus wore the laureate's crown, tumultuous social change took place and literary movements were born and died, but right up until the end, Garrigus seemed to work in a vacuum.

He once declared, "What we have today is an anarchy of words; no meter, no rhyme, no punctuation--anarchy."

Garrigus was best-known for writing rhymed tributes to his cronies in the legislature and composing Horatian odes like "Ode on the Groundbreaking for the San Luis Dam" to commemorate public occasions:

For decades, California's literary community bit its tongue on the subject of Garrigus. Occasionally, though, the annual poems he wrote and read on the closing of the legislature sessions wore their patience thin. "He wouldn't know an ode if it hit him in the face," complained one exasperated bard.

The Los Angeles Times weighed in, too, with a tongue-in-cheek appraisal of one of Garrigus' poems: "The sonnet is in iambic pentameter, contains the requisite 14 lines and clearly ranks with the best of Garrigus' previous work."

"I would never want to cast any aspersions on his character, but [Garrigus] wasn't a real good poet," says Joyce Jenkins, editor and publisher of the literary newspaper Poetry Flash. "I always had the feeling ... that it was almost a joke in the legislature, that it was sort of something they were doing for him, that they thought it was cute that he wrote verse, and it wasn't taken seriously at all."

Secretary of the Senate Greg Schmidt has a more blunt assessment. "Because [Garrigus] was into poetry, they gave [the laureateship] to him. He'd show up once in a while and write something, and everybody would go, 'Way to go.'"

With Garrigus' passing, some in the literary community have ventured hope that the next laureate will be a serious practitioner of the craft of poetry.

Ironically, while Garrigus' death went virtually unnoticed by the press, the death of Illinois poet laureate Gwendolyn Brooks last week has brought an outpouring of remembrances from those inspired by her prolific career. Brooks, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize in poetry, had immeasurable influence as a poet--and she held the laureateship since 1968, just two years less than Garrigus.

The California Arts Council, a state agency that didn't exist when Garrigus was named, is excited about the prospects for change. "For a long time now, we've been looking at the issue of the poet laureate, and the concept of naming a poet laureate has always had Mr. Garrigus standing in the way," says Ray Tatar, literature grants administrator. "But now--we're working on it."

Photograph from 'California Poems,' Huntington Press

Dead Poets Society

TRADITIONALLY, one doesn't get to be poet laureate of California by being an active poet or a great poet--or even, unfortunately, a good poet.

"One of the interesting things is these poet laureate appointments have been, in the past, really people who are not serious poets of great caliber," says Santa Cruz poet Morton Marcus.

A glance at the four laureates who preceded Garrigus is not exactly a walk through the halls of genius.

California's first laureate, Ina Coolbrith, was appointed to the post by the governor in 1915. Although Coolbrith palled around with the literary lights of her day, including Jack London, Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce, their way with words did not rub off on her. Coolbrith's verse is about as inert as a cupful of San Joaquin soil (the official state dirt).

After Coolbrith's death in 1928, there followed a parade of illustrious but uninspiring gentleman, beginning with English professor Dr. Henry Meade Bland. At the time of his appointment, Bland had published seven volumes of poetry; unfortunately, he died after only two years as laureate, so we'll never know what he might have accomplished.

In 1933, the garland passed to John Steven McGroarty, a journalist-turned-congressman originally from Pennsylvania. McGroarty's poem "The Hills of Santa Cruz" begins with the couplet:

McGroarty was also the author of The Mission Play, a three-hour pageant about the rise and fall of the California missions that terrorized the legions of schoolchildren who were forced to sit through it for more than two decades.

Ten years after his appointment, McGroarty died and was succeeded by Gordon W. Norris, who served until his death in 1961. Norris, at least, had a passion for the job and took to the road to read and lecture on poetry. What little poetry Norris wrote himself is not read today; he is still remembered, however, as an excellent shot with a rifle.

Bard, Ho

ACCORDING TO the definition in the California state archives, the poet laureate should "express adequately in poetry the wit, wisdom and beauty appropriate for honoring individuals, events, special occasions and the natural heritage and culture of the state."

Joyce Jenkins believes the job description is in dire need of modernization. "The poet laureate's job should be to enliven the art of poetry--how the art itself can help people and teach people and inspire people," she says.

Assemblymember Fred Keeley, who represents much of Santa Cruz and Monterey, is confident that when Sen. Burton and Speaker Hertzberg begin the selection process, they will be receptive to outside proposals. "Knowing the two of them," he says, "I think they would be very open to that idea and would be very touched that people would care enough about it to make suggestions."

The two legislators may be surprised to find out exactly how much people care. Tatar says the California Arts Council has already received numerous requests from across the state from literary centers and service organizations and small presses.

"Obviously there are so many terrific poets doing so many things that it's going to be tough [to choose]," Marcus says. "I hope that this does not break down--although I know it will--to a political fight. One side will be what school the poet represents; the other side will be whether it's going to be a Caucasian or a minority."

Jenkins, who also edits the California Poetry Series published by Roundhouse Press, says one of her top choices would be Juan Felipe Herrera, who teaches in Fresno. "He would be full of energy and vinegar, he'd shake everything up, there would be so many directions you could take it in."

Jenkins also cites Janice Mirikitani, current poet laureate of the city of San Francisco. She is "an interesting presence," says Jenkins. "She's working very hard for social change through poetry."

Marcus doesn't hesitate when asked whom he would nominate: Philip Levine. Levine taught at Fresno State for more than 35 years and "literally made Fresno a poetry center," says Marcus. "His poetry is so important; it addresses all the different classes of America."

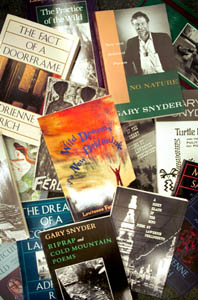

On close heels, Marcus says, is Santa Cruzan and National Book Award winner Adrienne Rich, and perennial California favorites Gary Snyder and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Whoever becomes the next high priest or priestess of California poetry will be able to mold the laureateship after his or her own image. True, the post is mostly symbolic, but symbols can be powerful. As national laureate Robert Pinsky pointed out, the term poet laureate "has magnetic connotations for people."

Of course there's always the dispiriting chance that the decision will come down to political back-scratching, to deals brokered in the smoke-filled rooms of Sacramento.

Charles B. Garrigus certainly wasn't coy about the fact that appreciative colleagues in the legislature tossed the crown to him. Witness the bit of doggerel he wrote in celebration of his 1966 appointment:

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Then patient padres passed across the land,

To toil with zealous courage for God's grace.

They taught the Indians husbandry by hand,

And Old World missions shaped the New World's face. Ode and in the Way: Charles Garrigus' poetic style ran to the hortatory and the hoary.

Ode and in the Way: Charles Garrigus' poetic style ran to the hortatory and the hoary.

One time, in Springtime, God made a perfect day,

He woke me in the morning and hid my cares away.The lark, the nightingale, the thrush,

Have nurtured poets with lyric mush,

But sweetest of all woodland notes

Are in the words, "He's got the votes."

From the December 13-20, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.