![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

East Side, West Side, All Around The Town

East meets West. The Donner Party meets Chinatown. Novelist James D. Houston examines the moment when two immigrant cultures came together on East Cliff Drive

By James D. Houston

Back in the late 1920s, when George Lee was a youngster, he met some descendants of James Frazier Reed, co-organizer of the legendary Donner Party. Before long he had become a friend of the family, and they offered him important encouragement when he first showed an interest in photography. It is a Santa Cruz story. It is a cross-cultural story. It is the story of California pioneers coming from opposite directions--one family from Canton, in southern China, one from Ireland, by way of Illinois--to meet here on East Cliff Drive at the edge of the Pacific. And it starts with a missing candy bar.

James Frazier Reed was born in 1800 and had crossed the Atlantic to the United States as a young boy, with his widowed mother. Forty-six years later when he started west with his wife and four children, at the head of a wagon train, he was an immigrant again, bound for what was then a northern province of Mexico.

Two generations went by, and Reed's grandson, James Frazier Lewis, grew up in Capitola, becoming wealthy in the candy business. He developed the world's first nickel candy bar, called the Frazier Lewis Victoria Cream. By 1915 he had made enough money to buy a steep-roofed estate house in the Twin Lakes district, still sometimes known as "The Frazier Lewis House." His mother, Patty Reed Lewis, the younger daughter of James F. Reed and one of the Donner Party's better-known survivors, spent her final years in this house, where she passed away in 1923. By the late '20s it was occupied by Frazier Lewis, two of his sisters and a Chinese cook named Wong, who lived on the ground floor.

From time to time Mr. Wong would visit Chinatown, near the river, to shop, to gamble, to call on friends. He always brought along pockets full of candy, which he passed around to the youngsters in the neighborhood. On one of these visits, sometime in 1928 or '29, Mr. Wong's supply ran out just before he reached 7-year-old George Lee, who was so disappointed that Mr. Wong promised him he'd have his piece of candy before the day was done. When it came time to catch the bus back to the east side, he brought the lad along.

For young George, it was a historic trip. He had seldom traveled east of the San Lorenzo River, nor had there been much reason to. The family's life was centered in the downtown Chinese community. George attended Laurel School, just a few blocks south. His father worked up the coast, as the cook at Wilder Ranch. Moreover, it was a long way, in those days, to the Twin Lakes district, which was still very rural, separated from the main part of Santa Cruz by a lot of open space.

"You could buy a live chicken just about anywhere," George recalls. "The Lewises themselves, they raised pigs. They had a pigpen right down there by the lake."

There was no shopping district yet, no small craft harbor, nor any state park to look after the wildlife around Schwan Lagoon. The lagoon, in fact, was part of the sizable piece of property that surrounded the tall Victorian standing out there by itself about a block back from the beach, with gardens on one side and a pair of sheds on the other--a backyard candy factory, as George was soon to learn.

Take the Candy and Run

In his eyes this was a strange and exotic part of the world, and he did not intend to linger. At age 7 his main objective was to get his Victoria Cream and head back home. "Any piece of candy was a big deal," he says, "especially one that cost a nickel. I remember in grade school when they asked for a nickel as a donation to the Red Cross, you had to think twice. In those days that was a lot of money."

Mr. Wong showed him around the place, let him peek inside the candy factory, where women sat at tables dipping confections into vats of chocolate. While George was on the premises, Mr. Wong decided to introduce him to the family. And much to George's surprise, they invited him to stay for lunch, about to be served in the dining room upstairs.

It was a high-ceilinged room, with redwood walls and moldings, a tiled fireplace, stained-glass window panels, and plate rails lined with china plates in the Blue Willow pattern. "I found out later," he says, "those plates really came from China."

Two mail-order catalogs were stacked on a chair so George could sit up high enough to eat at the table. At home he never used anything but chopsticks. He remembers that they showed him how to use a knife and fork. He remembers that French fries were served. And he remembers that there were cashew nuts, as many as he cared to eat. "They came from India," he says, "in a big 5-gallon can. Somehow that really impressed me. Nuts all the way from India!"

In the years to come George would dine at this table many times. The Lewis family liked him instantly and took him in, as if he were the grandson they had often longed for. Of Patty Reed's eight children, three were then still living--Martha Jane Lewis was 65, James Frazier was 63, Susan Augusta was 59. They all lived together, and none of them had married.

After a few more visits they had given the young fellow the run of the place. And it was a delicious place for a boy to run around in, a mystery house full of side rooms, stairwells, nooks and crannies, with an attic upstairs, and a lookout tower. On one visit George happened to open a door and came upon a room where materials for the candy business were stored--shipping boxes, packages of wrappers and some rather large chunks of chocolate brittle.

"This was like a hidden treasure," he says. "If you want to know the truth, I was never crazy about the taste of the Victoria Creams. They were pretty sweet, too rich. What I really liked was this chocolate mixed with brittle. A 10-pound chunk of that was quite a find."

In one of the ground-floor rooms there was another kind of hidden treasure. It had been a darkroom, where the sisters had stored some long abandoned camera equipment. When they learned that George had taken an interest in photography, they told him to make use of it in any way he could.

"By that time," he says, "I must have been starting Santa Cruz High. One of my friends from the Boy Scouts, he was an Italian kid, had come over one day with two boxes and said, 'I'm going to show you how to print pictures.' 'Print pictures?' I said. 'What's that?' But from that day onward I was hooked. And thanks to the Lewises I rigged up my first enlarger. Earlier in life, one of the sisters had been an amateur photographer. In that room downstairs they had all this stuff that went clear back to the 1890s--albums, emulsion plates, old view cameras that you set up on tripods. One thing I did was take those plates and boil off the emulsion. You couldn't use them for picture taking any more. But they made great windows. The glass was from Czechoslovakia. Glass nowadays has a greenish tint. This was the clearest glass I'd ever seen. No tint. Pure light came through. Each panel was about 8 by 10 inches. I cleaned off all the emulsion and built some new windows into our house downtown. And around that same time I took one of the old view cameras apart and made an enlarger from the lenses and the bellows. I attached them to the ceiling in my bedroom at home. I used a coffee can to hold the light. Some of my earliest prints were enlarged with lenses that came out of the Lewis family storeroom in the 1930s."

Story of the Doll

A few years later, George was called upon to photograph a precious family heirloom. During high school he had stayed in touch with the Lewises. By this time--the early months of World War II--he was nearing 20 and would soon be enlisting in the Navy. Susan, the younger sister, had passed away. Frazier Lewis was failing. Martha Jane, now close to 80, was making arrangements to donate various possessions to the museum at Sutter's Fort in Sacramento, including the single most famous artifact associated with the Donner Party saga.

The family Victorian had become a museum of its own, filled with generations of furniture, memorabilia and heirlooms, much of it linking the Lewises to the epic period of Western settlement. There were diaries James Reed had kept during the transcontinental crossing, documents he and John Sutter signed at the fort, and land petitions from the 1840s, drafted by Reed after he decided to settle in the Santa Clara Valley. There was a wedding dress Patty Reed wore when she and San Jose businessman Frank Lewis were married in 1856, and there was a 4-inch ceramic doll that 8-year-old Patty had sewn into the lining of her skirt, unable to part with this memento of the world they'd left behind in Springfield, Ill. After five months on the Western trail the Reeds had lost all their oxen. In the Nevada desert they had to abandon their final wagon, along with all belongings. Secretly young Patty carried the doll with her through the harrowing winter of 1846-47, when 41 of the 87 members in the party starved to death, trapped in the snows below Donner Summit. The following spring, after the survivors made it down to the Sacramento Valley, she revealed the doll to rescuers, and it immediately became part of a story that would be told and retold for decades to come.

By the early 1940s Patty's doll had been often written about but seldom seen, stored away in the drawers and trunks that moved with James Reed's descendants from San Jose to Capitola to the Twin Lakes house on East Cliff Drive. The picture George had been asked to shoot was among the first ever taken of this now-much-photographed icon of the pioneer era.

So there they were--you can imagine the scene--George Lee, whose father had sailed from China to San Francisco Bay in the 1890s, and Martha Jane Lewis, whose Irish-born grandfather had twice been an immigrant. See them together in the living room paneled with heart redwood from nearby forests. It is 1941 or '42. The big bay windows, facing south, are filled with light off Monterey Bay. They consider the shading, the angle of light. George crouches, lining up the shot. Martha adjusts the tiny skirt of the 4-inch doll that has become the poignant symbol of a child's inextinguishable hope.

"I had a Zeiss by that time," George says. "It was a good German camera. I bought it at Montgomery Ward for $14.95, right toward the end of the Depression. That was quite an investment. You figure my father was making sixty dollars a month back then. I brought it over to the house, and Martha got out the doll. At the time I had no idea what I was photographing--I mean, the significance of it. I didn't know much at all about her family's history. I just did it as a favor for a woman with a kind heart who had been so hospitable all those years, and she needed a picture of something that had belonged to her mother. I didn't even keep the negative. I gave it to the people in San Francisco who were printing it up, for a catalog or a booklet. But I remember the shot. I remember I got in as close as I could with that camera, so the whole doll filled the frame. It was black and white, taken in the front room. I haven't seen it since, though I think I would recognize it. Every time I see a picture of that doll I check the credit and wonder if it might be the one I took."

George didn't visit the house again. A short time later he was heading back across the ocean, the way his father had come, to serve as a U.S. Navy photographer in the South Pacific campaign. As was true in so many ways, those war years marked the end of one era, and the beginning of the next. While he was overseas the last Lewis passed away. When George finally got back to his hometown, the old house had changed hands, and Patty's doll had been transferred to Sutter's Fort, where it has now been on display for over 50 years.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Lee in 1943

A Young George Lee (left), with his brother Wee in 1931

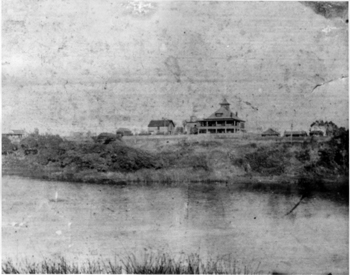

The Frazier Lewis House: On East Cliff Drive, circa 1910

James D. Houston is the author of The Last Paradise, In the Ring of Fire and other works of fiction and nonfiction dealing with the culture and history of California and the Pacific. Since 1962, he and his wife, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, have lived in the Frazier Lewis House. His recent novel, Snow Mountain Passage, is based upon the Reed family's experiences during 1846 and 1847.

From the December 11-18, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.