![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Vintage Spirits

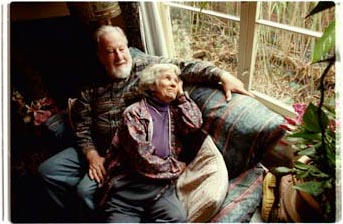

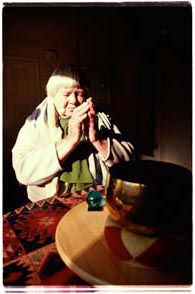

Easeful Interlude: Elizabeth Gips relaxes on the couch with her partner, Paddy Long.

High on life, four Santa Cruz women drink deeply from the barrel of experience

By Kelly Luker

ACCORDING TO Hollywood, this is how it's supposed to go for the fairer sex: Looks and attractiveness--and therefore value--begin to wane by the mid-20s, followed by a slow fade to black by the late 30s. By 50, women don't much exist except as dotty, dithering, dried-up candidates for the nearest nursing home. Unlike their male counterparts--who are apparently irresistible to girls of a grand-daughterly age--women in their 50s, 60s and 80s definitely don't get any.

If you're missing the Y chromosome, growing old sucks.

According to Hollywood.

Now, turn off the television, toss out the Cosmo and walk out of the theater into the light. Meet four local women who are rewriting the script for the second act of life. They may be considered mavericks now, but some of us like to think that they're merely surfing the first post-Summer-of-Love crest.

They have outlived world wars and Timothy Leary--and been shaped and hewn by both. Eighty-year-old Nina Graboi survived the Holocaust and concentration camps to become an elder in the psychedelic movement. Elizabeth Gips, 76, moved from an upper-class upbringing to communes and living on the streets of Santa Cruz, all the while working for social change. A committed Quaker, 82-year-old Mary Duffield can't remember how many times she's been arrested for civil disobedience. Nicola Geiger, 76, lost her two babies and husband to the bombs of World War II, then dedicated her life to the cause of peace.

Hollywood, if it saw these women at all, might dwell on the wrinkles. But this is what the cameras would miss: luminous eyes that look to the future, not the past. An absolute joy in being alive and being in the moment. Love, respect and hope--not bitterness--for the next generation. These women are what gorgeous is all about.

Nina Graboi

I WAS BORN in Vienna right after World War I. When I was about 19, Hitler came and took Austria over. I fled, but we were stopped in Casablanca and herded into a concentration camp in the desert. In this camp, in this desolate desert, the sun was burning down, and the hygiene was deplorable. But in the evening, we would set up crates and serve tea and would pretend we were drinking from the finest porcelain. I regarded everything as an adventure and as temporary. That may be one of the characteristics that has kept me young.

We came to New York as penniless refugees and became quite successful. I was living what people saw as the glamorous life. I was the woman who had everything. But all these things we were supposed to strive for seemed meaningless to me. It was in the early '50s and I was 34 and I began searching. It was the Eisenhower era, and I was alone in my search. Then one time I went to a seminar given by a Tibetan teacher, and I connected with some people who met once a week to talk about the very questions that have become my life.

Timothy Leary and I became good friends. It wasn't what he taught me, but his courage. I see Timothy and Ram Dass as the two most important men of this century. The world that I grew up in had this concrete wall between what you can see and hear and the unseen world that lies behind the senses, and there was Timothy punching holes in that wall. For that I am forever grateful.

I was 47 when I smoked marijuana for the first time; then later I took LSD. But I spent 12 years preparing for these sacred experiences. The reason the authorities were so scared by Leary and LSD is they knew that people wouldn't be the good little sheep that they were meant to be.

I always thought 60 was the age when I would call it quits--but it's amazing how wonderful the last 20 years have been. What I want to tell younger women who are afraid of aging is to not take themselves so seriously. I call my body "the space suit." It's what I'm wearing while I'm on this planet. If my space suit ages, I'm not attached, so I can watch it go through its changes. I know I'm eternal, undying and unborn, as we all are.

I was always the older wise woman and I have always cherished it. My friends would see me as the older lady and I never resented it. I'd like to be young and beautiful, but at what price? Why cheat myself out of one part of life that is as important as another?

I love these times. I'm passionately involved in the human species. I celebrate life.

Elizabeth Gips

I WAS RAISED in an upper-class family in Westchester, N.Y., during the depression. My mother was dragging me to left-wing discussion groups when I was young. Me and about four other girls formed a peace club when we were 9, to try to discover what war was all about. I'm grateful I had that; it separated me from the rest of the madness.

I got married very young and had two kids. I thought it was going to solve all my problems. I fell in love with a beatnik poet [in the mid-1950s], came out West with my son [Jeremy Lansmann, who eventually started KFAT radio], got divorced and lived the San Francisco life.

My son has been so good to me. He turned me on to psychedelics. He supported me when I dropped out completely. He's been a joy to me. The second acid trip I took I consider the most important day of my life. I was raised as a wishy-washy Jew, but [when I took acid] I died and was able to experience that and come back with a consciousness of God. When I came down I said, 'What am I going to do with the rest of my life?'

I had a big mansion in San Francisco which I sold. It was a gradual financial decline, but I loved it. I lived in a hippie van on the streets of Santa Cruz for a few years. I became a drop-out and organized a commune up on a piece of property above Nevada City that I had bought. I picked some odd people to live there.

I was one of the first people to listen to Stephen Gaskin [a famous leader of the '60s spiritual movement]. I went on the caravan with Gaskin and ended up on The Farm [that Gaskin founded] in Tennessee. Giving up tobacco was the hardest thing I've ever done, but leaving The Farm was the second hardest. I didn't know what to do, so I landed up at my son's radio station in St. Louis, and they said stay here and learn radio. That was 1971, and I've been in radio ever since.

We all need an antidote to the general malaise of the media, which seems to concentrate on the worst aspects. My premise is that energy follows attention. What you put attention in, you amplify. I'm trying to accentuate the positive. I'm not some Pollyanna, but I believe that change happens as more of us agree on directing towards compassion.

I want to talk about service. It's the key element in a contented and happy life, and I urge all older people to find places to put their energy that will be helpful to all of us. My spiritual life started with that LSD trip, but I don't think you need psychedelics. Once you get that [spiritual awakening], you have to spend the rest of your life letting other people know how to get that.

Mary Duffield

I HAD A MISERABLE childhood. My father almost killed my mother and brutally beat my brother. I ran away from home and changed my name and went to UC-Berkeley. It was the teachers that inspired me. I'm creating my new childhood. My daughter asks me why I'm so happy. I tell her I'm waking up every day knowing I won't be hurt. My parents became ill so they came to live with me. I thought I hated my father, but when I found out he was going to die, I discovered that I loved him. He was wonderful with my little boy.

My husband and I homesteaded in Alaska in 1942. Then I taught at Manzanar [the World War II internment camp for Japanese-Americans]. I couldn't stand the idea of these people being taken away. As a youngster I was so sensitized to suffering. I was so sure religion was wrong, but then I had a boyfriend who was alcoholic and started to go to Alanon. I wanted a religion, and the only one I could think of is Quaker, since it's so politically active.

All my life I realized that war is wrong and killing is not the answer. I've gotten arrested [for protesting] the Vietnam war more times than I can count. I was arrested outside of Fort Ord about three times. I've been fired four times [because] a teacher had to sign a loyalty oath. One time I had a sick child and elderly parents to support, but a Quaker couldn't sign an oath to support their country right or wrong.

My passion has been peace and communication. I want young people to live to their highest potential. I'm planning a trip to Belize [in the next week] and will be taking cassette tapes from school kids here talking about what their lives are like and how they plan to make a difference.

In a typical week, I go to Elderday to teach poetry, I teach Quaker kids on Sunday morning and then I have Hispanic youngsters come here with reading problems [whom I tutor]. I'm supposed to have Alzheimer's; I'm supposed to be two or three years into it, but I stay so active. I'm looking forward to the Grand Perhaps. I can't imagine a life more rewarding than mine.

I belong to the Hemlock Society. I believe that when my time comes, when I'm no longer this wonderful, joyous person, then I'm dead. Being alive is being conscious. My granddaughter says, 'How come you're the happiest person I know?' I'm lucky that everything I did is what I loved doing. I want everybody to have that, to be able to do what you love.

Nicola Geiger

MY FATHER was a Buddhist, but my parents never shoved it down my throat. When my father sat at meditation, that was the center of my life. Two important lessons they taught me: Every night I had to go over my day with my parents and decide what was harmonious and disharmonious--not what was good or bad. What it did was empower me to undo what was disharmonious. I learned I could change things. Also, every two or three weeks, I had to give something away. Not something I was tired of, but something I liked. It was very hard; sometimes I cried. But then I understood what my parents meant--they didn't want me to be possessive. This is one of the hardest lessons.

I really understood early on about justice because my parents spoke about that. I became very involved as a student in the movement against Hitler. After the war I worked in refugee camps. It was so painful because of what both sides did. I was married, and my husband disappeared; I don't know what happened to him during the war. Both my babies were killed in the war. I realized that I needed to live truthfully to make the world a better place.

I came over here in 1952. There were no Buddhist groups at that time, but I became deeply appreciative of the Quakers, who had had a practice for several hundred years to be truthful and to live in peace and to live in the light that would take away all wars. I became very involved with the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movement. I did a lot of sit-ins at the segregated restaurants on the road to Washington, D.C. I lived at the Resource Center for Nonviolence [in Santa Cruz] for eight years.

Practicing Zen means to live in the moment, yes? And that's how I've been living. I've done that with utter delight. All the pain and grief, I'd accept it and work with it at that moment. The preoccupation in this country to remain young--what a waste of time! I have no fear of getting older or sick. I will take this as it comes. I have pulmonary trouble. I can only walk between here and the bathroom or kitchen. But if I'm careful I can stay awhile. The secret is to be grateful, to not compare with others. I don't have much but I'm grateful for what I have. It's about gratitude and generosity and to be of service to one's friends and community.

It's like breathing in and breathing out--everything is reciprocated.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

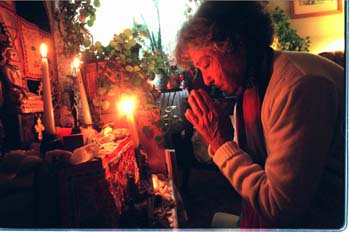

Burning incense scents Nina Graboi's snug little apartment high on Beach Hill in Santa Cruz, offering a welcome contrast to the drizzling gray day outside. Pothos vines snake around the walls and ceilings, highlighting Hindu artifacts, tapestries and Latin American artwork. Speaking softly with an Austrian accent, Nina outlines a life that weaves through concentration camps, wealthy suburbs, Woodstock and Timothy Leary's living room. The week after our interview, she is headed to a conference in Kalamazoo, Mich., with 30 other leaders of the consciousness-raising movement--including Laura Huxley, Ram Dass and Albert Hofmann, the scientist who discovered LSD.

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

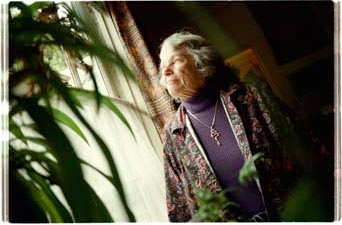

Pulmonary disease is making it harder for her to breathe, but Elizabeth Gips has no trouble chatting animatedly about life. Elizabeth has put the gift of gab to good use this past couple of decades working in radio. She has hosted a weekly show on KKUP called Changes and has developed an accompanying Web site. She lives near downtown Santa Cruz with Paddy Long, a big, bearded bear of a man whose voice hints at an Irish brogue. We take a tour through her garden, which has created an oasis of serenity from the honking horns and gas fumes of Mission Street. When asked her age, Elizabeth quickly replies, "Seventy-six and proud of it."

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

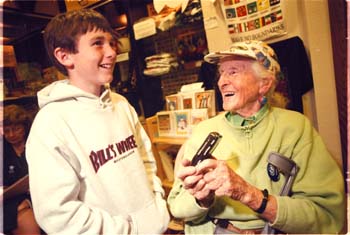

Wearing a pair of large Earth-globe earrings, Mary Duffield moves like the butterflies that emblazon her baseball cap. She's laughing and smiling, and there is something that stirs in her even when she's sitting still. The octogenarian Quaker is a study in contradictions: a lifelong peace activist who fights against war and capital punishment, she is also an ardent supporter of the right-to-die organization the Hemlock Society. Brutally abused by her father as a child, she has made it her life's work to cherish and teach other children. Diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, Mary is sharper than most folks half her age. She talks excitedly, breathlessly, of the ideas she has. Mary grew up in Glendale, Calif., and worked as a teacher. She taught English and journalism at Santa Cruz High School for 20 years and retired in 1968. After living on her sailboat for 30 years, and taking her students on sailing trips to Mexico, Mary finally moved into a mobile home in the Live Oak neighborhood and donated her boat to the Sea Scouts.

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

Right past the small apartment's front door bubbles a sprawling indoor fountain that accents the tranquillity radiating around Nicola Geiger. As we sit down, she rings a Buddhist prayer bell given to her by her father 60 years ago. Only then do we begin talking. With a round, full face capped by a bowl of white hair, Nicola speaks with the strong accent of her native Germany. She has survived imprisonment, torture, rape and the murder of those closest to her--legacies of her work for the underground Resistance during the war years. Instead of retreating into bitterness, anger or fear, however, Geiger finds her refuge in acceptance. A dedicated peace activist until poor health forced her to slow down, Nicola now conducts spiritual retreats in Santa Barbara every few months.

George Sakkestad

From the December 9-16, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.