![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

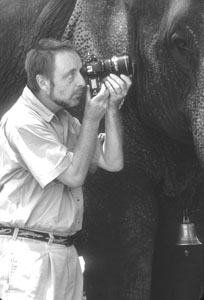

Optic Nerve: Two decades of acclaimed work in the field of nature photography has given Lanting the confidence to get some unique shots of the animal world.

Wild Wild West Side

The husband-wife team of Frans Lanting and Chris Eckstrom has drawn international acclaim for writing about and photographing the world's wildlife. Their new gallery gives the public a unique peek at their life's work.

By Sarah Phelan

Frans Lanting says that if he had an animal totem, it would have to be a chameleon. It's not that the world-famous nature photographer identifies with the woggly-eyed, color-shifting critters. Rather, it's that his work requires him to adapt to whatever animal he's working with--from hanging out in subzero temperatures with emperor penguins in Antarctica to tracking impalas across the parched Kenyan grasslands.

"All animals are fascinating, so rather than say I'm a member of one particular clan, I'd rather move in and out of this or that clan," says the Dutch-born Lanting, speaking in fluent but slightly accented English, as he gives me a guided tour of the studio that he and wife, Chris Eckstrom, an editor and producer and a former staff writer at National Geographic, are opening this week on Santa Cruz's West Side.

The studio not only adds the couple's considerable talent to the burgeoning renaissance that Kelly's Bakery and Bonny Doon Vineyard kicked off in that part of town last year, it also allows Lanting and Eckstrom to do everything from research for field work to photographic workshops and exhibits all in one space, and makes Lanting's work more accessible to the public than it was when he and Eckstrom based their operation in their Bonny Doon home.

At the heart of their studio lies the Frans Lanting Gallery, whose walls are adorned with images selected from a body of work that has filled 16 books, illustrated numerous issues of National Geographic, Natural History, Audubon, Stern, GEO and Life, and been exhibited in major museums worldwide.

Indeed, for more than two decades Lanting has documented wildlife and the human relationship with nature in environments from the Amazon to Antarctica, and his work has increased worldwide awareness of endangered ecological treasures in some of the remotest corners of the world.

Along the way, he has scored plum assignments ranging from a search for the fabled bonobos of central Africa to a unique circumnavigation by sailboat of South Georgia Island in the subantarctic, not to mention a yearlong odyssey to assess global biodiversity at the turn of the millennium, and stories on India's Western Ghats and New Zealand. And then there's the fact he was named a Photographer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society in 2001.

'Penguins on Iceberg, Antarctica 1995' by Frans Lanting. Courtesy of www.lanting.com.

His Own Toughest Critic

But despite receiving numerous prestigious awards, including the BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year and the Sierra Club's Ansel Adams Award, Lanting--who is also a columnist for Outdoor Photographer and serves on the National Council of the World Wildlife Fund--is startlingly self-effacing when it comes to selecting images for inclusion in his newly opened gallery.

"In 25 years of taking photographs, there's not a whole lot of images that stand the test of time and which I dare to put on these walls and call fine, or photographic, art," he says, his eyes sliding over prints of cougars, frogs and orangutans. "All of these instances involved a lengthy process of knowing where to go, when to be there and, in the end, serendipity, the surprises of animals and light that all come together very rarely."

When working on assignment for National Geographic, he says, he has to connect the beauty of his subjects with the specifics of science and conservation, while at the same time telling a compelling story.

"Whereas this is a very aesthetic set of images that can endure outside of any context," he says, standing in front of Emperor and Offspring, which depicts a sleek-coated adult penguin mobbed by a bunch of impossibly puffy chicks somewhere on the ice of Antarctica.

"This came from an expedition to the Antarctic in 1995 in which I was camping on sea ice for a month, something that takes a lot of planning, because you can't go back to get more stuff."

Lanting recalls that to get that series of photos, he had to wait in Patagonia for a couple of days to fly into Antarctica in a cargo plane, then transfer to another plane, before touching down on ice and finding a colony of the penguins, at which point he spent a week just hanging around, figuring out what to do and how and when.

"In this case, one adult had just come back from a lengthy journey across sea ice, and she or he--I don't know which--then had to find its offspring that it left behind, and it can only do that by calling," says Lanting.

With temperatures dipping to 40 below zero and lower ("It's a bit nippy," says Lanting, with a rare but warm smile), Antarctica isn't exactly the kind of place you'd want to spend prolonged periods moving about stoically and slowly--unless you're mimicking an emperor penguin, which, of course, is precisely what the chameleonesque Lanting did in his quest to capture the perfect penguin moment on film.

"Physically, I had to get very deliberate, because that's how penguins are," he says. "They don't make sudden movements. And since they are only about 4 feet tall, I had to sit on my knees or crawl, slowly shifting closer, then stand there for an hour waiting for something to happen."

One of the results was a classic parenthood shot titled Emperor Penguin Family, in which two adults flank their ridiculously woolly chick, a shot Lanting was able to capture only because he heard one parent trumpeting its arrival to the other.

Animal Instincts

In addition to his willingness to make like a penguin, his ability to pick up on the subtle but unfailing signals that animals put out is a central component of Lanting's phenomenal success.

Consider, for instance, that animals get upset if you get too close.

"Scientists call this 'critical distance,'" he says. "If you get any closer, you're invading their privacy bubble, which varies according to the weather and other factors. If it's windy, animals become nervous. If the wind comes at you, you can get closer to mammals that are very sensitive to smell. You can't approach the same colony of penguins the same if you visit on two separate days."

Surprisingly, Lanting's training ground for his career wasn't the African jungle or the Canadian tundra, but the beaches of Santa Cruz, where he shot sanderlings, those little, long-billed seabirds that race in flocks across the slick wet sand in a seemingly eternal search for food.

"I pursued them on the beaches off West Cliff and along the North Coast," recalls Lanting.

He first came to Santa Cruz in 1978 to conduct postgraduate research in environmental studies at UCSC, then became a photographer and never looked back. This year, he was elected as a trustee to UCSC's Foundation Board.

In his post-sanderling era, he's developed physical endurance and an unnervingly intuitive eye for the classic moment--like the ethereal Penguins on Iceberg, also shot in Antarctica in 1995. He stood on an icebreaker to take the shot, and the chinstrap penguins give the enormous blue iceberg, which was in fact the size of a cathedral, a sense of scale.

"By framing it quite tightly, the upper edge of the iceberg becomes surreal, so you don't quite know what you're looking at, but it's pleasing nevertheless," he says.

Besides learning a lot about the rest of the animal kingdom, Lanting's work has also brought him to a greater understanding of the human psyche, by way of his audience's response to his work.

"Certain colors resonate deep in our psyche, to times before humans existed, " he explains. "Essentially, we're primates, whose vision is rooted in the need to look for things that are brightly colored, like reds, yellows, blues, which is one reason why we respond so well to primary colors. But in nature, such colors usually punctuate, rather than dominate, the earth tones."

Looking around the gallery, it suddenly becomes clear that most of the images involve a lot of greens and browns, with only a splattering of color, with the exception of an aerial view in Fall Colors, Alaska 2002, where the foliage is ablaze with hues of red, orange and yellow.

Other images provide a mirror of what people like to think about animals, says Lanting, pointing to Impalas Alarmed, Kenya 1985. The shot seems to capture impalas in a parched cover of grass below an intensely azure sky. People like to picture such animals frolicking under sunny skies, but in reality, says Lanting, the impalas were huddled beneath a storm sky "that was really threatening, with a thunder cloud approaching."

Also hidden within the shot is an insight into the social structure of impalas--the group is a herd of 16 does dominated by one buck, who is almost invisible, aside from his horns.

"By the buck's presence, every impala knows that this is not just a gathering of does, it's his harem," says Lanting. "At least that's how the buck sees it."

In a similar vein, Dancing Bears, Canada 1997, seems to depict two bears waltzing together, but turns out to be a play on what people like to see as opposed to what's really happening. For Lanting, the charm of this specific image, taken in bitterly cold weather while sitting in a vehicle equipped for moving across the tundra, was capturing the moment when two sparring bears actually look like they're a dancing duo in step with each other.

"People can't help but take an anthropomorphic perspective. They can't accept animals as totally other beings," he says. "'Anthropomorphism' is an ancient expression that in its current incarnation has led to the animated characters cranked out by the movie studios in Hollywood."

Another theme that pervades many of his shots, including Atlantic Puffins on a Grassy Knoll, Iceland 1994, is the rules of animal behavior. The birds pictured in this particular shot are on the edge of a large colony in which each family has its own burrow, and where single puffins cannot wander, Lanting explains.

"There are prescribed paths from the outside of the colony to individual puffin territories within, but there are a number of areas on the edge like this one, which are like a club or cafe, where single birds can hang out without feeling the pressure to defend," he says.

'Cougar Face, Belize 1992' by Frans Lanting. Courtesy of www.lanting.com.

No Technophobe

Lanting's years in the field have helped him quickly gauge what will and won't work technically. And while some treat digital photography with suspicion, because of the possibility of manipulation, Lanting has welcomed it for the way it helps him faithfully reproduce color.

"It's the equivalent of the dodging and burning that Ansel Adams did in his darkroom with black and white negatives, but which was impossible with color," he says.

Another advantage of digital is that he can produce much bigger prints--Red-eyed Tree Frog, Panama 1998, for example, was successfully enlarged to cover the entire outside wall for a museum exhibit of his work in the Netherlands.

He does want to point out, however, that he's not out there using digital "to clone in additional elephants or create sunsets that didn't exist." And if the colors in his prints are unusually intense, it's not because of digital manipulation, but because Lanting likes to work at the edges of light that occur early in the morning and late at night.

Take Lion at Twilight, Kenya 1996 in which a lion's eyes are seen shining eerily out at the camera from within stands of bluish grass. Knowing that males typically linger after the lionesses have gone, Lanting positioned his Land Rover along the path the females had already taken, and was able to get a shot of his subject just as he was waking.

"The lion is trying to keep a low profile, because signaling his presence makes it hard to hunt," he says, "but by using a flash I was able to give him more illumination. So the light shining back from his retina is the reflection of my strobe, but it also reflects the intensity, the amazing focus that cats have when they're on the prowl."

One of the few underwater photos that Lanting has ever dared to put his name to is Water Lilies Suspended, Botswana 1989, which involved slipping into the water, making as few ripples as possible, so as not to disturb the sediment--or alert the crocodiles.

"Even so, I still had to wait 40 seconds for things to settle down, which left me with 15 to 20 seconds to look around and take some shots, before going back to the surface for air," he recalls.

He repeated this process for two days during midday, because those were the only hours when the sunlight penetrated the water, which is why the lily pads in the shot are so beautifully backlit.

"The water is blue-green because when light penetrates water it immediately loses the red and everything turns to blue--except the lily pads, because they are at the surface," he says.

Many other gallery images are set on or around water, such as Gray-headed Albatross, South Georgia 1987, shot during a three-month stint in a sailboat, and the ethereal Tortoises at Dawn, Galapagos 1984.

The latter shot involved a strenuous hike carrying the expedition's water supply uphill, an effort which still did not spare the crew having to filter water from the tortoise pond through their shirts by the end of the trip--a measure they undertook, Lanting says with what some might say is classic Dutch obliqueness, "because the water was full of a lot of the stuff that comes out of the end of the tortoise."

Working At Home

Not all Lanting's images of animals were shot in the wild. The heart-warming Orangutan Twins, Borneo 1991 was shot at a rehabilitation center for orangutans who've been injured, orphaned or left homeless by deforestation and poaching, while Cougar Face was also shot in captivity in Belize, 1992, even though mountain lions, as cougars are also known, roam wild in Santa Cruz County.

"I wouldn't dream of approaching a wild cougar, because I'd never find one, and if I did I could put myself in a dangerous position, because even with a long lens, I would still be within critical range. So either the cougar would react by charging or would flee," says Lanting, explaining how he came to capture this mesmerizing shot of a splendid male cougar by setting up with a long lens right outside the cat's enclosure.

"At first, it was perturbed, and had that classic 'What do you want from me?' look that cats do," he says. "Then it relaxed to the point that there was no perturbance, but it was still registering annoyance, which anyone who has a domestic cat knows about. On top of which it was a beastly hot and humid midday, so the conditions subdued him."

The resulting shot is so textured, you feel you can stroke it, even though you know you shouldn't. And like all of Lanting's work, this portrait breathtakingly fulfills his stated aim of "portraying creatures as ambassadors for the preservation of complete ecosystems."

To capture such classics, he and his wife, Chris Eckstrom, whom he met in 1988 at the National Geographic's headquarters in Washington, D.C., travel for three to five months each year, devoting the remaining months to researching and processing their fieldwork.

"We knew of each other, but had never met, because Chris was traveling furiously on assignments, as was I," says Lanting of his first encounter with Eckstrom, who worked as a staff writer for National Geographic for 15 years, contributing to over a dozen books.

The couple then engaged in what Lanting describes as "the most romantic of courtships imaginable," in which they variously had assignments in adjacent countries or were separated by continents, only to rendezvous under the stars in Botswana.

"We slept in an old canvas tent, where we only dared to go to the outhouse with a flashlight to make sure we didn't surprise the leopard who was drinking from the bowl," he recalls, which leads the strikingly beautiful Eckstrom to interject, "although the hyena was usually there!"

Finally, the couple decided to settle on the West Coast, as opposed to the East Coast, a decision Eckstrom says was "easy," even though it involved her having to give up her staff writer position.

Since then, she and Lanting have worked nonstop, producing books together, a venture that has also allowed Eckstrom to develop her talents and amass a whole range of new skills, including producing books from concept to delivery and making video documentaries.

And after checking out various locations in Santa Cruz, the couple decided to move their multipronged enterprise to the West Side, because, says Eckstrom, "it has a bohemian spirit that suits us. And if we can contribute to the renaissance of the West Side, that will make our move even more exciting."

"We've never been in a position to make a showcase, nor was it as easily accessible," she says of their former studio. As for their new space, she states, "We're proud that there is no other gallery between San Francisco and Carmel that offers anything like this."

Their love of their new space, however, has not prevented them from preparing to travel to Hawaii on an assignment involving volcanoes, and then onto Colorado, in between working on a book about the evolution of life on earth--a project which, says Lanting, is "much more connected with the scientific view of earth and involves a very different portfolio than what people will view in this studio right now."

Having visited so many ecological hot spots in the world, Lanting feels ecological awareness is in a critical phase.

"Thirty to 40 years ago, there was widespread arrogance and ignorance among people in developed nations," he say. "Now there is a rapidly growing realization that we need to resolve issues as a global community. We're beginning to build institutions that will enable us to come up with solutions that work across the spectrum of political and economic divisions, but whether we'll be able to do that before we run out of options--that's the biggest question of our time."

The new ? Gallery is devoted to local artists--and ready to take on the dicey business of making an art space work in Santa Cruz

By Sarah Phelan

Up until last week, the standard explanation for why there are so few art galleries in town was that art galleries just don't work in Santa Cruz. When asked why, people might say we are simply too close to San Francisco and Carmel, which already have well-developed gallery scenes, or too far-out imagewise to attract well-heeled patrons--twin arguments they could support by citing the names of all the galleries that have come and gone in the Cruz in recent years.

But all that threatens to change with the opening of not one, but two new galleries this month. One is housed in the newly opened Frans Lanting Gallery on the West Side (see cover story), the other is located on Pacific Avenue in a three-story building devoted entirely to local artists.

The name of this locals-only gallery? Until last week it was called Vapor, a name that, in the immortal words of gallery co-director Kirby Scudder, has subsequently "evaporated."

So what do we call it now?

"The ? Gallery. Seriously," says Scudder, who is threatening to drop his last name so he can be on equal footing with his co-director and Uninamer, Chip.

Scudder, a relative newcomer to our humble burg, says the notion that galleries can't work here is nonsense.

"Every other town with a condensed urban area like Santa Cruz has a successful gallery district," he says. "The problem isn't that we're haunted against galleries, but that the right combo of factors hasn't until now been in play.

But with a prime location and a long-term business plan, Scudder believes that situation will now change, as the gallery works to promote the enormous local pool of talent, with 6,000 artists estimated to be living in Santa Cruz County alone.

And in a sign of the electronic times, the ? Gallery is also working with Cuban-born Marcella Siera, who runs artists.com, a website designed to promote local artists.

"Marcella has a print shop in Felton and a similar charter to us," explains Scudder. "Rather than artists having to provide us with a stock of prints, now Marcella will simply print copies of the works people order online."

A New Yorker by birth, Scudder moved to the Bay Area 2 1/2 years ago as a sales rep for an East Coast business. When that job dried up during the dotcom bust, he approached the San Jose Redevelopment Agency, who agreed to let him show his work in empty retail spaces, an arrangement that led to him selling 40 pieces and helping curate other artists' work. In December he moved to Santa Cruz and repeated the process with the Santa Cruz Redevelopment Agency, who agreed to let him exhibit in the old Wherehouse space where he sold 35 pieces in the 4 1/2 months before the space got snapped up to accommodate the newly opened Urban Outfitters.

It was due to the success of that project that he, along with Siera, Chip and Anita Elliott, got invited to do the project at 1319 Pacific Ave., which will house the ? Gallery for 2 1/2 months--and hopefully beyond.

"If I had lots of money, I'd buy this gallery up, then gobble up other spaces nearby where I'd start competing galleries," he says. "That's what happened in Carmel, it's how you develop a thriving gallery scene."

For now, he's contented to exhaust himself working long hours to birth this particular baby before worrying about other offspring.

"It's a labor of love. People would be surprised at how limited [are] the resources we currently have. The good news is we got slammed the first weekend with at least 500 people each day asking, 'Why didn't this happen before?' People want to see art in a space that's not cluttered," he says.

As for sales, Scudder isn't expecting things to fly off the wall

"Art is a commitment, an emotional thing that people want to think about. For most, art is not an impulse buy, rather a hunt, with a person coming back again and again before they make a decision."

And above all, Scudder believes that change is possible.

"I've heard all the naysayers, but we can believe this project can and will succeed. The first week we opened, when I was killing myself with the long hours, this woman came in, made her way around, then kissed me and said, 'God bless you and I hope this works for all of us.' I thought, 'I'm exhausted, but that was nice!' And kisses are good."

Artists featured until Dec. 21 are Melanie Arndy, Nick Atchinson, Kaia Cornell, Ea Eckerman, Bridget Henry, Jack Howe, Nancy Howells, Sally Jorgensen. Roger Lee, Gary Lundblad, Andrew Stanbridge, Joshua Salesin, Kirby Scudder, Cynthia Siegal, Michael Singer, Michelle Stitz, Kathryn Stowell and Paul Titangos.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Courtesy of www.lanting.com

Photograph by Frans Lanting

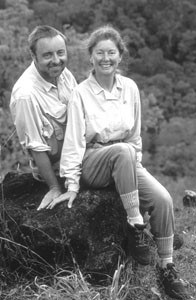

Animal Magnetism: Frans Lanting and Chris Eckstrom have opened a studio in Santa Cruz that includes a gallery of Lanting's photographs.

Photograph by Frans Lanting

Water Proof: Eckstrom and Lanting at work on location.

The Frans Lanting Gallery, located at 207 McPherson St., Suite D, Santa Cruz, one block off Highway 1 near the Mission and Swift Street intersection, is open daily 10am-5pm with an exclusive selection of images available as fine prints, books, posters and videos. Call 831.429.1331, email [email protected] or visit www.lanting.com.

Art's Question Mark

From the December 10-17, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.