![[MetroActive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Ending It All

Canadians wonder what to do with their 'Last Night' on Earth in Don McKellar's millennial vignettes

By Richard von Busack

IN THE LAST DAYS of man in Toronto, society has broken down in a self-effacing, repressed, polite way. That, in short, is the plot of Don McKellar's new film, Last Night, made before but released after his co-written art-house hit The Red Violin. In a series of vignettes, some neurotic people face up to an appropriately vague end of all life on Earth--the sun blowing up or something--which is efficiently scheduled for midnight.

In the heart of the city, young people are rallying for the big countdown. Meanwhile, Patrick (director McKellar) decides to spend his last moments alone with a bottle of champagne and a good record. His family members, who have united around the table for one last badly cooked turkey, protest this antisocial way of checking out. (Patrick's mom doesn't miss a final chance to guilt-whip her son. Whining like a theremin, she says, "When you go home, alone, at midnight, you'll remember that your parents weren't so bad.")

The loner, however, is flushed out of his apartment by the needs of Sandra (played by Sandra Oh), a tough yupette anxious to get back home to her husband before the Event. To help the woman, Patrick has to round up the car from his too-cool gear-head pal Craig (Callum Keith Rennie), who is listening to the countdown of the 500 best songs of all time on the radio and trying to have every sexual experience he can order over the Internet.

Meanwhile, in a usual formaldehyde-blooded part, David Cronenberg plays a functionary at the gas company, making sure that every customer is thanked one last time for their patronage.

I'M INTERVIEWING director McKellar on a warm fall day. As a foretaste of Apocalypse Soon, the Blue Angels are playing a deafening game of chicken with the skyscrapers. Last year, Last Night won the Prix de Jeunesse, the youth prize, at the Cannes Film Festival.

"A lot of people know that I won the prize, but what they don't know is that this year, 1999, The Blair Witch Project was the winner. I wanted the distributors to remember that because my film is clearly capable of that kind of financial achievement," he jokes.

The release had taken so long because it was the strategy to push for an opening closer to the millennium. Yet McKellar hadn't intended Last Night to be a millennial film, per se. Or so he claims; in some interviews, he has said that he was asked by his producers to make a film about the millennium and accidentally made it instead about the end of the world.

McKellar came from an upper-middle-class family and began as a theater actor. Though still a young man, he has turned up in a number of films, including Highway 61 and eXistenZ. The novice director said that his first scenes were the most difficult--taking in the empty streetscapes of Toronto awaiting the Big Event.

"I thought this should be a cool and economical way to have a big impact," he says. "And the scenes would reflect a lot of the films I loved when I was growing up: The Omega Man and On the Beach. Of course, as an economical idea, it was a big mistake.

"If anything, it's more expensive clearing streets than filling them. And these scenes were during my first days of filming, so it was chaos. I had visits from fire trucks four times because of the smoke bombs. People were so angry with me for closing the streets--there's just nonstop cars honking in the background. But I'm really happy with the way it worked out; it was a unique look for Toronto, and Toronto's a hard city to get to look unique."

Toronto is the utility city, having played New York, Chicago, and even Boston for Good Will Hunting. "When my film first showed in Toronto, " McKellar says, "there were actual gasps in the audience when I mentioned Toronto locations. It's a bizarre thing--that's because Toronto isn't that distinctive-looking. [It has] a lot of unusual buildings and all, which you can use because nobody knows what Toronto looks like."

In Last Night, Sandra Oh, who can be seen in the auction crowd in The Red Violin, gets one of her largest parts since the Vancouver-based film Double Happiness. Of his female star, McKellar says, "Sandra has strength and dignity that makes her stand apart from anyone I was casting. And she was supportive to me, which I needed because I was acting [in Last Night] as well as directing."

Those who remember Double Happiness fondly can cite Oh's snippet of Blanche DuBois from A Streetcar Named Desire as proof that cross-cultural casting works. "You're right about Sandra," McKellar says, "but the whole cross-cultural issue is something I hadn't thought much about. I didn't set out to cast an Asian, and it didn't seem to be an issue, maybe because I live in Chinatown. But when I went to France everyone asked me, 'Why did you do this interracial love story? What was the symbolism?"

FILMS SUCH as Double Happiness can be made in part because of the Canadian government's support of the arts. As McKellar explains, "The Canadian directors you've seen--Patricia Rozema, Atom Egoyan and David Cronenberg--were originally funded by public money and still are to various degrees. Canadian filmmakers are doing well internationally, but they wouldn't have been there in the first place if it weren't for this funding.

"That's the flip side of that Canadian niceness and gentility, the Cronenberg side," McKellar continues. "Isn't it strange to imagine a film like Cronenberg's They Came From Within being financed by public money? The public funding of films worked exactly as it could be hoped.

"These directors were able to develop idiosyncratic voices, to the point where they were able to get funding on their own. The same model spawned so many great movements like the German new wave and the wave of Australian films in the 80s. I think continuity to the next generation of filmmakers is broken now, because all of that funding is almost gone."

McKellar and Francis Girard are listed as co-writers on The Red Violin and 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould. About the art of collaboration, McKellar says, "Together, we came up with an outline, and I think he wrote out a list. Then I fleshed out the outline as a script. I mean the actual script that people read: the writing side, the prose, and the dialogue. I would be proud when I could come up with a formal idea. I think the collaboration taught me how a script can move into more formal ideas organically."

I'd had a few arguments about the nature of The Red Violin with other viewers over whether the instrument was cursed or inert. McKellar thinks for a moment before offering his interpretation. "I think there is a curse--a sort of a circumstantial curse. It was the kind of curse that comes from matching energy."

As an actor and director, McKellar is interested in abstracted, dreamy men. He has a recurring role on a terrific television comedy series that hasn't been brought to the U.S. yet, Twitch City, in which McKellar plays the laziest man north of the border. Why I find his sensibility amusing is that there's not a self-pitying streak to match the inertia (the same is, thankfully, true in the films of Atom Egoyan and David Cronenberg). Morose detachment is so much more interesting than the dramatized self-hatred of a lot of young American actors.

In Last Night, this fantasy of composure at the end of the world shows that British streak in the Canadian. It's seen in how Cronenberg's character foregoes one last pleasure in favor of one last responsibility. Cronenberg's own choice of the most boring way possible to spend his last hours isn't just a cheap joke. I'm writing this on Nov. 11, the day of the Armistice at the end of the Great War. Rudyard Kipling, whose son was killed in the war, wrote epitaphs for some of the soldiers.

Here's one quatrain he wrote on the occasion of a soldier killed while taking care of a call of nature, a not-uncommon happenstance for a soldier's death: "I was of delicate mind. I stepped aside for my needs,/Disdaining the common office. I was seen from afar and killed ... /How is this matter for mirth? Let each man be judged by his deeds. I have paid my price to live with myself on the terms that I willed."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

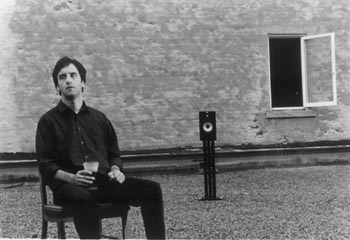

Indie Direction: 'Last Night' director (and star) Don McKellar plays a loner who wants to face the apocalypse quietly.

Cross Currents: As Sandra, actor Sandra Oh drives 'Last Night' in the same way that her cross-cultural romance drove 'Double Happiness.'

'Last Night' (R; 96 min.), directed and written by Don McKellar, photographed by Douglas Koch and starring David Cronenberg, Sandra Oh and McKellar, opens Thursday at the Nickelodeon in Santa Cruz.

From the November 17-24, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.