Down on the Street

Passing the Buck: Homeless transient Skippy has been panhandling on downtown Santa Cruz's Pacific Avenue since breaking his leg almost a year ago.

A glimpse inside the lives of the scraggly souls who call the sidewalks of downtown Santa Cruz's Pacific Avenue home

By Marc Herman

SKIPPY WAS LOOKING BAD, brittle. His head was a shrunken blond praline, and his voice scraped when he talked, making everything he said sound pathetic or sarcastic. He hunched on the sidewalk outside the Rage clothing store on Pacific Avenue with his legs out and his feet in black basketball sneakers big enough to hide a swollen ankle.

That something has happened to Skippy is obvious. Whether he deserves any pity is not. It is a hard call to make. He has been a fixture on Pacific Avenue for almost a year now, using his broken leg as leverage for spare change. Sitting with him, I witness a range of reactions. Countless pedestrians look away uncomfortably. Occasionally, he'll have brief chats with strangers who eventually offer a dollar. Others give him hostile shouts.

That the leg injury is the result of being "jumped by a couple of frat boys," as he says, is somehow difficult to accept, but why he would lie about it is also unclear. His situation is not doing him much good, after all.

"The street is starting to get the best of me," he says. "I'm starting to slip a little." It is difficult to imagine the place he'd slip to, looking at where he already is: bumming on the sidewalk day after day, getting thinner. He motions to three twentyish shoppers loaded down with bags from Starbucks, all taking pains to avoid interaction with the man on the street. They snap their heads forward and fix their eyes toward the horizon, marching past him like soldiers. "Have a nice day," Skippy says. One of the three shoppers smirks--the salutation sounded too much like a play for guilt--before the group breaks ranks and eases back into a slower mall saunter.

"They don't want me here," Skippy says. "But what they don't realize is that I don't want to be here, either."

He pauses for a moment to put a marking pen back in his pack. He unzips it and pulls the top back. The bag is painstakingly organized, with his pens in embroidered holders, beside a novel and a folded shirt.

"This is not the way I choose to live," he says.

Skippy says he hopes to gather $35 and make a break for Humboldt County. He heard something about the Headwaters Forest, where an anti-logging demonstration is supposed to last six months. He thinks he can get a job in the protest industry.

"I could work security," he says. "Not like a bouncer. I could stay by the gate and check people's name tags."

It is not apparent what gate or what name tags he is talking about.

That he is injured is undeniable. Skippy's left leg is twice the size of his right, and has been that way at least since the beginning of the summer. The injury has taken so long to heal, skepticism is inevitable. But if he is faking the situation, he should be hired by Shakespeare Santa Cruz to play a slow death scene.

A Grimy Gray Area

SKIPPY AND THE REST OF THE buskers and beggars who hang out on Pacific Avenue put a face to Santa Cruz's homeless problem. But they do not offer an accurate representation. The overwhelming majority of local homeless people do not hang out on Pacific Avenue, do not panhandle, do not appear notably disheveled. They have children (or often are children), and they frequently sleep indoors, with friends or family. Most of them have jobs, according to county officials. Of the 3,000 homeless officially identified in the county--the real number is probably up to double that--the majority are employed part or full time, according to county officials.

That these facts are hardly known, though they inform the bulk of assistance efforts in Santa Cruz, is a testament to the amount of attention paid to the downtown street people, rather than the folks living in cars or with friends or lining up for one of the 38 beds offered by churches every night.

Most of the homeless in Santa Cruz county are invisible.

Under federal law, a homeless person is defined not as someone living on the street but as someone lacking a stable housing situation. Of the people in that sort of situation countywide, people like Skippy are a vast minority, as a momentary visit to the River Street shelter makes immediately apparent. The shelter is full of families and individuals who would not be recognizable as homeless if they weren't there.

This basic mathematical fact--that Skippy isn't typical--has not drawn public debate away from other long-standing conflicts in town. Nuisance loitering, the camping ban, even the bad music played outside the Gap by guys with out-of-tune guitars hog the publics' attention span. This may be the last great mystery of the homeless debate in town. Also the most damning.

Until families and the working poor start camping out on Pacific Avenue along with the hippies and the gypsies and the disabled vets, the homeless debate will concentrate on issues of nuisance rather than issues of health and welfare. Anyone who says otherwise while complaining about panhandling has never been to a county shelter for as long as five minutes.

The homeless downtown are not the homeless your taxes and your public servants deal with the most, despite the long and horribly circular debates about sleeping and begging, debates so skewed from the meat of the issue--toward a few dozen people and away from a few thousand--that public information on the matter is at worst duplicitous and at best simply wrong.

Meanwhile, public attitudes about the citizens of the street are oversimplified to fit the black-or-white debate. They are seen as either the smelly bums that Lee Quarnstrom attacks viciously in his Mercury News column or the saintly victims that Paul Lee crusades for tirelessly. And Skippy is still there on the sidewalk, with nowhere to go.

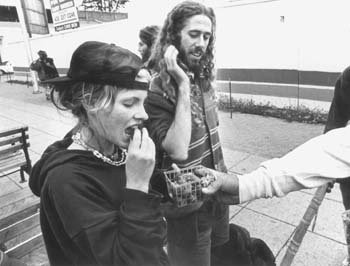

Small Taste of Freedom: Mandy and James on Hippie Corner, eating strawberries donated by one of several people who bring food by regularly.

Limping Onward

SKIPPY MOVES THE ANKLE gingerly, in pained arcs, and walks with a cane. He says he worked until a year and a half ago "pounding nails," paid under the table, until he found it impossible to continue because of the injury. He was married and lived in an apartment "over on the Eastside," he says, but he doesn't give an address, and the various friends who drop by don't remember the place. One who stays a short while, who asks to be called Baby, refuses to say much about the house, and after a few tries I don't ask anymore. He has a fancy backpack and wears mascara above and below his eyes, a garish penumbra of glittery blue that reminds me of Daryl Hannah in Bladerunner.

Skippy has a lot of friends among the street kids, most of whom look older than he but are in fact 10 years his junior. The clerk in Rave, who has taken in a few of those street kids and walks by Skippy every day before work, says she thinks maybe a speed problem is really what keeps him on the sidewalk.

Leaning on a display case full of bracelets, she offers the sort of vague, occasionally accurate medical knowledge that now inevitably circulates through discussions of suburban trends: new narcotics from San Jose, tattoos rehashed from either 17th-century Polynesian tribes or Lompico bikers, ritual scars and intimate piercings copied unknowingly from Irian Jaya via San Francisco rave organizers.

Skippy wears a few telltales of the alternative universe--tattoos of spiderwebs and peculiar glyphs, scarabs that would look intimidating on a larger man. The dirt on his arms obscures the green color. They look like lesions.

Skippy, whose given name is Chris, says he is from Illinois. I suggest I may be able to find him the $35 he wants but ask why he wants it. He talks about a ride that left without him earlier that week, bound for Eureka. He offers to go to the bus station with me to buy a ticket. Whatever the story, the $35 seems fair.

Skippy is a smart guy, well spoken and clever. Having spent time with him on a couple of occasions, I have a suspicion that he is trying to get out of town to escape some sort of trouble, maybe even break some sort of habit. Still, a sign saying, for example, "I need $35 to get away from a very dangerous guy who has me strung out," probably would not play very well, so he has come up with a scheme, which almost seems plausible, or at least a good start, if you sit on the sidewalk with him long enough.

Skippy denies the speculation. Fair enough. Security guard at the Headwaters protest, he says. He looks wilted and worn, he can barely talk and he is going on the one-year anniversary of a still-broken leg.

Dirty Business

FOUR HOURS LATER, THE SUN IS down and Skippy is gone to the cliffs near the pier, where he has been staying at night. Others remain on the street. Some are homeless, some are just hanging out for the evening. The older homeless hang out on the north end of the mall. The day-trippers on their way through, mostly young, stay farther south, around Hippie Corner, at Pacific and Cathcart.

Pacific Avenue is a mix of the peculiar and the impenetrable--at night, the deeply coded. Living there would be like living in an Edward Gorey drawing. Wolf lives there, or nearby.

Wolf does not panhandle. "I myself, I'm against panhandlers because that brings more cops and causes unnecessary conflicts," he says. He is a thin man in his 50s, with a gray, trimmed beard, a baseball hat and black jeans tucked into his workboots. "I don't panhandle myself, and I wish people wouldn't. That's coming from a homeless person."

Wolf is from Portland and has been on the streets 10 years, the last six in Santa Cruz. He says he had been working as a surgical assistant in Portland before he "got into some trouble." He says he got divorced and started drinking, then using drugs. And that, he says, got him banned from working in medicine. He now works as a gardener, charging "eight to 10 dollars an hour. I'm worth that, I think," he says.

It's about midnight when we head out to get some pizza. He says he does not like sitting on the sidewalk, where we had been. In the indoor light he looks more bedraggled. The tucked-in T-shirt, straight cap, efforts to make himself presentable, now do not hide the fact that his clothes hang off him slightly off-center, the effect of having been slept in. He does not look affected or aggressively mangy, like the hippie kids on the other end of the street. But he does seem badly mussed.

"Let's face it," he says, chewing the pizza down three bites at a time. He notices me staring and apologizes, for which I then apologize--we go around a few times with this before he swallows and gets to talking again. "I'm still a dirty person. I can take one, two showers a week. I could get in the ocean, but that's not the same thing. We can go to Emeline [shelter], but Emeline is so backed up."

He said he last worked 10 days ago, mowing a lawn for a family on the Westside. He says he makes between $35 and $85 a day, gets a motel room when he has the money, and finds jobs through ads in the Sentinel for day labor.

"You build up a clientele," he says. "They don't want to trust you, of course, so you have to be patient and give them a chance to, and then they realize you aren't going to rob them, and then they tell someone else. Once you start a rapport with these guys, it works out."

He says the lack of trust is easy to understand. "There's drugs, there's alcohol. I'm not going to say we're all good people. A lot aren't."

In Wolf's opinion, a key reason homeless people come to Santa Cruz is that they can get away with things that they can't do elsewhere.

"It's safe here," he says. "It's a lot easier to rip off [a grocery store here] than to rip off someone in Berkeley. This is an easy rip-off town. And you feed off the generosity of others. That was hard for me to do for a while."

"But I respect these business owners. They are watching out for themselves because they are being taken advantage of sometimes."

He speaks of the police with similar equanimity.

"They ticket people sometimes. It's their job. I understand that. They don't make the rules, they just enforce them."

In the restaurant, his tea arrives. So does Gary Fossey, another homeless man in his 40s, but hard to distinguish as such. Gary, a self-described gypsy, had spoken with me that afternoon. He told me then that he was rebelling against the consumer culture.

He played a Japanese flute badly and claimed devotion to a monk's lifestyle: "The path of the monk is to give up his own self-interest," he had said. "Are anybody else but the homeless doing anything around here that's not related to a paycheck?"

I had gotten nasty at the time, asked him, in a less than charitable tone, who paid for the food at the soup kitchen. He'd started playing his flute again rather than answer, looking at me with bemused condescension.

Wolf says he does not know him but has seen him around.

"The hippies are mostly younger," he says. "I think they are mostly yuppies getting out of the house. They think that there's power in numbers, but really they're just cluttering up the street."

Homeless Go Home: A homeless man catches some sleep in one of several illegal Santa Cruz campsites (this one is located at Pogonip) that handle the massive overflow of homeless people that the scarce shelters in town can't house.

Hippies Cornered

FIFTY MILES NORTH, A YOUNG couple stand hitchhiking by a taco stand beside the highway in Half Moon Bay. He says his name is Rainbow, a 24-year-old from the Sierra foothills, and she is Mariah, an 18-year-old from Seattle. They climb in when I pull over and say they're heading for the Food Not Bombs dinner at the Santa Cruz Town Clock.

Talking in the car is like pulling conversation from kindergartners who haven't had much social interaction. Rainbow and Mariah have a post office box in Santa Cruz. They used to live in the old warehouse on Chestnut Street where Logos records was located after the earthquake.

They eat from the soup kitchen beside the River Street shelter sometimes, but this time they are figuring to just pick up the mail and head to Idaho, to Mariah's mom's place.

Listening to Mariah and Rainbow talk, it seems that their lives are mostly possessed with the details of food and shelter. "Sometimes we panhandle," Rainbow says. "But Santa Cruz is a pretty cool town." They explain "cool" to mean that they can eat without having money, and get around by bumming rides. They don't have much to say about anything else besides the scrambling for basic needs, except to occasionally misquote various mystics.

Mariah and Rainbow seem to be largely narcissists, citing Castaneda obscura on and on, but missing that more famous line about the dangers of repeating history.

"We choose this," Rainbow says a few times, urging libertarianism. It becomes a mantra over the 50 miles. It is an oddly impractical concept as Rainbow explains it, if only for the constant planning involved.

Finally I ask if they are happy and push Mariah, the one named after the wind, as to why she left Seattle. Both shrug. I ask if they know any homeless people who live in Santa Cruz. They say they don't. They are by now a little irritated with the questions.

Mariah finally realizes she can choose not to answer me, clams up and watches the water breaking south of Pescadero. A half-hour passes silently.

At the traffic light at Western Drive, Rainbow perks up when he sees someone at his favorite hitchhiking spot, just north of the Linda Vista market. The hitchhiker is heading north, an older man with a cardboard sign that says San Francisco. It is a common through route, Rainbow offers.

When former San Francisco Mayor Frank Jordan clamped down hard on the big-city homeless, many had come from there down to Santa Cruz. The same happened with Seattle.

Hard Lessons

ON THIS TRIP, RAINBOW AND Mariah were coming from Oregon. They said they liked the nomadic life, the culture of a gypsy population: they are living the endless Deadhead tour redux. When we get to the city line, a regional problem becomes a municipal one, however. Rainbow may be part of hippie nation, but he is a resident of Santa Cruz this night.

I ask Rainbow what he thinks of the various migrations. He says he doesn't know and shrugs, again. He talks with Mariah about whether to get that night's dinner from Food Not Bombs after all. Life appears to be an eternal quest for free tofu. I drop them off at the city parking lot, and they head for Hippie Corner.

"There were these two kids, they were Deadheads, y'know, but they were good kids," Wolf says. "I had to show them around. They were a little stupid. They didn't even know how to get cigarettes. That's how stupid these kids were."

How do you get cigarettes?

"You know, butts, you get some papers and then a few butts, and you crush up the butts and gets what's left and there's your cigarette." Oh.

"And food. There's a steady stream of homeless coming between S.F. and here, San Jose and here. They don't know the town, and I keep telling them it's a good place but you can't push people too hard."

Such as?

"You won't starve. You can go to Georgiana's at 11 o'clock. Peet's will put out some pastry and coffee. Not every day. The Hindquarter will put out the leftover meat."

Then what?

"I used to have a place down at the end of 17th," Wolf says. "Down by, what you call it, Twin Lakes beach. Down where the grass is this tall." He waves a palm over his head, like a magician.

"You can get under it and no one can see you. We used to go to that warehouse there and get the pallets. You can set your tent up on them."

And where do you live now?

"I've got a place now where I stay. I stay alone, lone Wolf, I guess." He smirks at his own bad joke. "Who knows, if someone else is there, maybe they're stupid and they give you away."

Wolf is not a saint, but rather the sort of ambiguous story that might have walked out of a Willie Nelson song. He says he was raised in Kankakee, Ill., 75 miles south of Chicago. He has been in jail and has only been clean from heroin for about two years. He has four purple hearts and three medals for bravery from two years' service in the Vietnam War. He also has a restraining order out on him from his ex-girlfriend.

"I think of this as a learning experience," he says. "I've been on the streets almost 10 years, but I am learning more every day."

Disappearing Act

HALFWAY BETWEEN HIPPIE Corner and the post office, five men are gathered at 3 a.m. They are all drunk but one, Randy, a construction worker with an apartment in San Luis Obispo but a job in Los Altos. He is camping in his truck by the beach and commuting over the hill until the work is done. He is asking everyone where to camp.

Another man is playing with a marionette, telling obvious jokes and forcing half-accurate vaudeville impressions around a cigarette. A man named Seth is drunkenly giving directions to the semi-permanent homeless camp up in the Pogonip, at the end of Golf Club Drive.

A fourth man, named Hard Rock, is talking about having met another man named Hard Rock in another town, and telling how he gave the guy a hard time. It is a locker-room scene. Stupid, drunken comments and obligatory affirmations.

There are no homeless women on the mall at all that night. Those with families are up at the Pogonip camp, or in cars out in the woods, or parked by the Davenport cliffs; those homeless because they lost their roof when they left a husband or boyfriend are in one of the five beds at the women's shelter, or at the River Street shelter or in the Catholic Relief Service's 38 beds, or in a motel between other options, or they are heading back home for lack of any other choice. The homeless hippie girls are with their hippie boys, or crashing on sofas or vans, up in the Pogonip or in the woods near the UCSC.

No one has seen Skippy.

He has disappeared. No one knows him until he is described, and then no one saw him leave. Hard Rock, after half an hour, tires of defending his good name, says he is going to sleep, gathers up his sleeping bag and walks off up Walnut Avenue.

He walks a block. Then two. Then he turns again, to wherever he sleeps until morning, when it is legal. Then he disappears.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

From the Nov. 13-19, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)