![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Prudent Paranoia

Local experts examine the credible yet disastrous 'what ifs' that might one day befall our county

By Mike Connor

Mike Dever is paid to be paranoid, and rightly so. He's the Emergency Services administrator for the County of Santa Cruz; it's his job to anticipate and prepare for horrendous disasters. And in this county, there's no shortage of potential disasters for which to prepare.

Risk of floods, tsunamis, wildfires, landslides, earthquakes and soil liquefaction--beautiful Santa Cruz County has it all, and that's not even including relatively new potential hazards like terrorist attacks and avian flu pandemics. Errant asteroids would have to get in line. Yet we're still here, and not because we've simply learned to relax in our flu-proof bubbles and enjoy the soothing vibrations of earthquakes while we wait for our daily tsunamis to extinguish our ever-present wildfires. That might be the geologic

look of things, but as far as day-to-day

life goes, Santa Cruz County is a decidedly peaceful place to live. But it's a temporary condition that inevitably nurtures a sense of complacency about natural disasters. And for people like Mike Dever, that's

a problem.

Most natural disasters can't be prevented, but with proper preparation, some of the disastrous effects can be avoided, or at least mitigated. But that preparation costs money that Dever doesn't have.

The Lone Ranger

The Office of Emergency Services used to be located in the basement of the County Building, a five-story structure built on a flood plain in a liquefaction zone. Sensibly, the office was relocated to higher ground among the gently rolling fairways of the Delaveaga golf course, though its exact location at any given moment is apparently debatable.

"The Office of Emergency Services is wherever I'm standing," jokes Dever. Kind of funny, yet kind of true. The Office of Emergency Services, established in 1994 by the County of Santa Cruz, consists of ... Mike Dever.

"In a lot of jurisdictions," says Dever, "there are actually enough funds available to local offices of emergency services that they actually have services. Like they have cadres of people and caches of equipment and supplies and so forth. But in this county, we're a small operation, we're greatly dependent on grant funding to operate, so we really don't have services per se, other than some information sharing and acting kind of as an information clearing house."

Dever's office is located within Santa Cruz Consolidated Emergency Communication Center, which houses emergency dispatchers for the cities of Watsonville, Capitola and Santa Cruz. Also housed in the building is the Emergency Operations Center, which is automatically activated whenever a disaster requires coordination among multiple emergency jurisdictions. It's basically one big room where personnel from various disciplines--police, fire, transportation, public works, care and shelter, etc.--can coordinate face-to-face, and it's Dever's job to run it.

The coordination the EOC provides on a local level ties into a larger system of emergency coordination on a statewide level. Emergency management has been effectively standardized in California, so that, at least in theory, multiple disciplines of emergency services should all be able to function together seamlessly, or work just as easily with teams in other parts of the state. That way, in the event of a major regional disaster, emergency personnel can be deployed from anywhere in the state to assist with relief and recovery efforts.

Dever, who has worked on disaster planning in Santa Cruz for the pat 18 years, says this coordination system, known as the Standardized Emergency Management System, or SEMS, is what the Gulf Coast needed, but didn't have.

"Katrina was kind of the classic example of how bad an idea that is," says Dever. "I talked to fire personnel who have gone down to help with recovery. They had a meeting with all the fire chiefs in the area, and [the chiefs] had to do introductions. Here, everybody knows who their neighbors are, and you work together.

We have common plans and we have common responses."

Our common plans and responses used to come from a two-feet-thick stack of red binders, cumulatively called the Multi-hazard Functional Plan, which had an index of every conceivable incident and its appropriate response.

"It was very impressive," says Dever, "but the problem was, it didn't work, because you would have an earthquake, and it said what you're supposed to do, but it never quite matched what that earthquake or flood or fire actually did. So that was the model we had in place for Loma Prieta, and they made beautiful doorstops."

The current plan, called the Operational Area Emergency Management Plan, is not much more than an organizational flow chart that clarifies roles, but doesn't rigidly specify exactly what needs to be done in the event of a disaster.

That would be the job of the EOC, and Dever is enthusiastic about the situation.

"I think the citizens of Santa Cruz County should really feel pretty good," says Dever. "Our agencies have been in the forefront of making sure that they communicate with each other."

Dever says 37 agencies in the county meet on a bimonthly basis for discussion, training and strategizing meetings.

Homeland Insecurity

The question is, does it all work? The problem, says Dever, is that we don't have the money to find out. A large-scale drill is extremely expensive, but it's something that Dever says big counties like Santa Clara can afford to do because they're allocated more funds through the Department of Homeland Security--the organization created by the federal government in response the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

For smaller counties like Santa Cruz, Dever says Homeland Security is an administrative headache, because the same amount of time spent on an application yields a fraction of the funds.

"Forty percent of my time and sometimes more is devoted to Homeland Security grant management," says Dever. "and it's really been a drain on our ability to do all hazards planning, the training and the exercises--we just don't have the time to do it. That's a concern I've got is if something does happen, our ramp up time is going to be longer, it's going to be more cumbersome, because we haven't had the time to pay attention to that sort of thing."

Dever says that even though "all hazards planning" is the latest buzz phrase for FEMA and the DHS, the DHS grant for Santa Cruz County amounts to about $65,000, which Dever says isn't enough to do very much at all.

"Look," says Dever, "you can spend $10 million in a minute in a big disaster. If you're not willing to put in enough money before the disaster to actually build what we think should be an effective response, you're going to have more and more Katrina-like responses."

For Dever, a lack of proper preparation would be disastrous for the county, and for his career.

"That'll come back to bite me at some point," says Dever. "Something bad will happen, someone will come to me and say, 'You knew about, why didn't you do something about it?' Then I'll be the next Mike Brown."

Common Geologic Sense

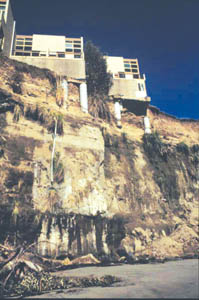

Of course, another key aspect of long-term disaster planning is figuring out where not to be in the first place. For UCSC professor Gary Griggs, that means not building your house on eroding coastline, no matter how rich or famous you are. His newest book, Living With the Changing California Coast (UC Press; 400 pages; $24.95 paperback), is essentially a consolidated source of historical and scientific information that coastal real estate agents might find meddlesome, but that anyone else interested in coastal land use would find invaluable.

"We're basically trying to draw people's attention to fact that coast is eroding," says Griggs. "People should know about it before you spend 10 million on a house."

He points out that erosion along the coast sometimes happens gradually and in long cycles, but sometimes very quickly, say, when big chunks fall off in a storm. The changing rate of erosion has, in the past, allowed geotechnical reports to be skewed, often in favor of coastal development. Then, when those same developments get hammered by winter storms, the owners then turn around

with "updated" reports to make their case for a seawall or some other form of

coastal armoring.

Charles Lester, the central coast deputy director of the California Coastal Commission, says that the permitting process has been changed to forbid seawall construction in front of new developments, but whether or not it will hold up in court remains to be seen.

In the meantime, are all these questions about development going to be settled by a giant tsunami? Not likely, says Griggs. He points to what he calls a "sensationalist" article in the San Jose Mercury News that showed all the areas in Santa Cruz--the Boardwalk, the beach flats, the police station, all of downtown, etc.--that would be devastated by a 50-foot wave.

"Why not make it 500 feet?" asks Griggs. "There's no basis for it."

Griggs explains that we're not anywhere near the same type of tectonic activity that led to the tsunami in Indonesia. There's a big canyon in the Monterey Bay, but no underwater subduction zone. A big asteroid could theoretically cause a huge tsunami, but according to Steven Ward, a researcher at the UCSC Institute for Geophysics and Planetary Physics, we're not due for one of those until 2880.

Meaning what? Meaning that you should be more fearful of other drivers on the road than giant waves. Of course if one does happen to show up, Dever's advice is to head for the hills--doesn't matter if it's Mission Hill, Branciforte Hill, the City on a Hill or over the hill, just get on up.

1, 2, 3, Evacuate!

The problem with evacuation,

Dever points out, is gridlock.

"The '50s are over," says Dever. "[Evacuation] just doesn't happen

that simply."

Thousands of people trying to get to the same place at the same time is a recipe for disaster, which is why the tsunami guide on the website of the OES recommends hoofing it if traffic is bad.

Dever is a big advocate of preparation and self-reliance, and repeatedly emphasizes the importance of education (there is a wealth of information on the OES website) and what he calls "situational awareness," which includes simple observations like water rushing through your house, but also more thorough understandings of where you are in relation to your children during the workday, and how you can get to them in the event of a disaster.

The Fire Department's Community Emergency Response Training (CERT) is one way for citizens to educate themselves about local disasters, and make themselves useful in the event of one. Since 1996, over 400 residents in the city of Santa Cruz alone have been CERT-ified.

"I can't predict when [a disaster] will happen or where it will happen," says Dever, "but what I can predict is, it will take time for the government to respond, it physically takes time to put it in place."

Terrorists Among Us?

What Homeland Security money has gotten us are resources to deal with terrorists--the one threat about which Dever says we're pretty much in the clear.

Nevertheless, Dever says the emergency responders were temporarily thrown off balance when faced with the terrorist anthrax scare.

"If someone attacked with a Chlamydia bomb, we'd have it covered," says Dever, but since it was an anthrax scare, he says there was confusion as to who should deal with it. Was it a health department issue or a law enforcement issue?

"It was like, 'Who's got the ball?'" says Dever. "What we did--to this county's credit--is we got the leads of any agency that has anybody to do with these disciplines, and we got them in the conference room here for two full days and said we're not leaving until we figure out how we're going to handle this."

Despite the creepy infringing of civil liberties that's been the hallmark of the DHS, such was not the solution here in Santa Cruz.

"We don't have secret teams running around gathering information and building dossiers on people," says Dever, but what they do have are things like satellite phones and brand new HAZMAT toys, which the county can also use to deal with any of the 364 sites in the county that use or store hazardous chemicals for agricultural use. Dever says that preparation for terrorism has forced interdisciplinary coordination to the point that they're actually better prepared for all kinds of emergencies--like, for instance, a mass vaccination for avian flu.

"What we've been able to do is take from that an understanding of what other disciplines can do, what their responsibilities are, what they can't do, and what they'll need help with, and be able to interactively work towards a common solution," says Dever. "If we have to do mass vaccinations for the flu, the healthy agencies can help us with the technical issues related to transport, storage and dispensing of pharmaceuticals, but they don't know about setting up big logistical events. Well the fire guys do, so we've been working on a process where the fire chief's association has been working with public health and we asked them to work out, what's our plan for mass vaccination?"

Ultimately, argues Dever, the capacity to sustain ourselves for the FEMA-recommended 72 hours--along with coordination among Santa Clara, Santa Cruz and Monterey counties--will prove crucial in the event of a regional disaster. Whether it be a powerful earthquake coming from the Roger's Creek Fault, the Hayward Fault or the Portola Valley window of the San Andreas fault, most of the state's attention would be focused on San Francisco.

"The Portola Valley fault could go at about a 7.2, and we'd feel that just about like Loma Prieta, so we're not out of the woods yet," says Dever. "And if that happened, it would be hard for us to get anybody's attention. So we would have to be able to fend for ourselves."

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Change Is Gonna Come: Gary Griggs' new book considers the downside of living in paradise.

For information about disaster preparedness, visit http://sccounty01.co.santa-cruz.ca.us/oes/oesmain2.htm, call the American Red Cross at 831.429.3600, or the Fire Department at 831.420-5280. Gary Griggs will give a presentation on his new book at a special event at the Seymour Marine Discovery Center on Thursday, Nov. 17, at 6pm. There will be a wine and cheese reception afterward; admission is $10 for the general public, $6 for members. Griggs will also discuss his book at Bookshop Santa Cruz on Thursday, Nov. 10, at 7:30pm.

From the November 9-16, 2005 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.