![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

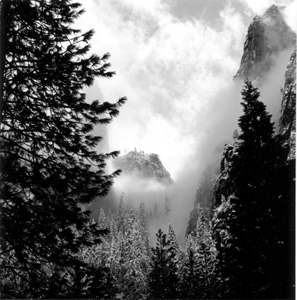

Photograph by Seema Weatherwax Seema Weatherwax's 'Mountain Clouds.' Now You Seema She's 98 years old. She's worked with some of the most famous photographers who ever lived. And she's finally taking her rightful place in art history--right here in Santa Cruz. It's high time you heard about Seema Weatherwax. By Sarah Phelan Everyone thinks nursing homes are where seniors get walkers, hearing aids and an addiction to bingo. But for 98-year-old photographer Seema Weatherwax, the Santa Cruz-based La Posada nursing home was where she finally got her muse on. "Friends in La Posada always ask, 'Where do you get all those nice young men?'" says Weatherwax, gesturing at the two relatively youthful men who are currently hanging out in her apartment--archivist Charles Hanson and photographer Jason Weston. Both were instrumental in helping Weatherwax put on her first photography exhibit three years ago, enter Open Studios last year and stage her upcoming two-day exhibit, a joint endeavor with Weston that will be on display Nov. 15 and 16. Weatherwax's young admirers, for their part, feel like they've tapped into nearly a century's worth of some of the most fascinating and important history of the photographic age. They're also seeking to right the industry sexism that kept Weatherwax from thinking of herself as a significant photographer for decades, even though she shot alongside some of the most influential photographers of her time--including Jason's great-grandfather, Edward Weston--and ran Ansel Adams' Yosemite darkroom for four years. "In those days, I considered myself a darkroom technician," says Weatherwax, whose work has in the last few years been donated to the Smithsonian, Stanford University and UCSC. She'd probably still be waiting outside a darkroom somewhere, if she'd waited for permission to enter what was then considered the inner sanctum of the most revolutionary art form of the 20th century. Instead, the Ukrainian-born, British-educated Weatherwax slipped through the darkroom's back door, shortly after she arrived in Boston at the tender age of 17 with her sisters and widowed mother. The year was 1923 and the young Weatherwax, unable to afford college, took a job at a photo lab in the hope of putting to use the knowledge she'd gained while studying her first love, chemistry. But instead of dabbling in chemicals, Weatherwax found herself at the front desk. A long-awaited break came when she applied for a job at another store. "They asked if I knew how to print and I said, 'Yes', which wasn't a lie, because I had observed how to print. I'd just had never done any printing," she recalls. Sexism wasn't just rampant at work. Married at 18, Weatherwax was told she was frigid when her relationship didn't work out, a theory she later disproved with Chan Weston (Jason Weston's grandfather), whom she met through the Film and Photo League. The two became partners, which in turn led to Weatherwax becoming involved with "the whole darn Weston clan," including Chan's father, Edward, whom Weatherwax jokingly refers to as "Edward the Great."

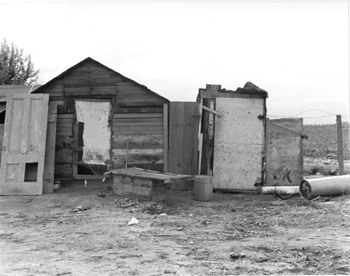

Seema Weatherwax's 'Shacks.' The Ansel Factor In 1931, Weatherwax headed for Tahiti. Photos from that era show a pretty, young woman wearing a flowered sarong. What they don't reveal is that Weatherwax, bored of vacationing, had set up her own makeshift darkroom in a basic bamboo hut. "But I still only thought of myself as just having fun," says Weatherwax of her work, which was of high enough quality to get Ansel Adams to entrust his darkroom to her--a job she accepted in 1938, when she grew weary of Chan's unwillingness to commit to a monogamous relationship. "But even Ansel had no idea how much photography I was doing. He occasionally saw a print of mine and liked it--he felt I had the 'feeling,' which is why he trusted me‚ but when I went with him and Edward Weston into the field, I was seen as a friend and not a third photographer, even though I was there taking photographs, too." Her career reached a crossroads in 1941, when she met her second husband, Jack Weatherwax, a writer who was very involved with social justice issues. "I felt he had a message, which was mine, too, but that his had to take precedence. This was what I felt I had to do to be with a man I liked. He could not have fitted his life to mine. I was the one who had to make a steady living," she says. Which was why Weatherwax traded Yosemite and its bears and snow-capped peaks for the heat of Los Angeles, where she punched the clock working in film production while her husband continued his writing. Though he was supportive of her work, she was dealing with her own insecurities. "Jack never put me in second place," she says. "In fact, he was very proud of my work, but I put it in the closet where no one else could see it." Luckily, her longevity allowed her to re-evaluate her work and her view of gender bias in the industry when her husband died in 1984, shortly after the couple retired to Santa Cruz. "I had to stop and think, 'What the heck am I gonna do with the rest of my life?'" she says. "But if I hadn't had that wake-up jolt, I might have continued to accept that sexist role." Ironically, by the time she got her first solo exhibit at the Mulberry Gallery her eyesight was failing, which is one reason she came to rely on Charles Hanson, who acts as her archivist and publicist, and on Jason Weston. "He's my printer," she says of Weston. "He's way more than an assistant." Weatherwax is a devoted mentor, as well. So much so that she decided not to do Open Studios this year, when she learned that Weston had not been accepted. Instead, she chose to do the collaborative exhibit with Weston on Nov. 15 and 16. She says she has enormous respect for his work. "He's reproducing that same type of quality prints as photographers in the past century did," she says.

Seema Weatherwax's 'Rails on Salt Flats.' Double Vision Weston, who first met Weatherwax a month before his grandfather Chan died, says they share an interest in photography, family and politics. "We always have lots to talk about," says Weston, who used the darkroom at Foothills College to make his first prints for Weatherwax, before moving to Santa Cruz and building his own darkroom. He does note, however, that his darkroom is too tall for Seema, "because it was built for me and because she can't see to work any more." "And then there are all the buttons," interjects Weatherwax. "I was not brought up with everything being mechanized. I'm used to counting 'one, two, three, four' in the dark room." "And then there are things such as polycontrast filters that allow me to change contrast in half steps, whereas Seema used three different kinds of paper to achieve the same effect," says Weston. Still, he says he takes great pains to print her photographs so that they come out her way. " I think I print with a little more contrast, so I print hers down half a contrast grade," he reveals. "The critical thing is that it's collaboration and I'm acting as her hands and eyes on the scene." Fortunately, Weatherwax's sight is such that in the right light, she still can make some judgment calls. "I can still say, 'Crop horizontal, vertical,' but without Jason, forget it," she says. "I wasn't getting the feeling I wanted with other printers." As to which photographs will be in her upcoming show, Weatherwax notes that many of her negatives have been lost or destroyed--including the ones she accidentally burned after the earthquake. "You and Brett!" interjects Weston, in a joking reference to yet another member of the photographic Weston clan, Brett, who burned his negatives because he didn't want anyone else printing his work. "Brett and Ansel Adams were diametrically opposed," he says. "Ansel saw negatives as the score and the print as the performance of the score, whereas Brett saw the negative as the stepping stone on the way to the print. Ansel allowed people to print everything from his negatives, while Brett didn't. 'No one can print the way I do,' he is said to have said."

Seema Weatherwax and Jason Weston. A Life in Pictures Meanwhile, Hanson has organized Weatherwax's work into a timeline that begins in her teens. "What we learn from Seema's work are all the details of what it was like to grow up in Leeds or to live through the flu epidemic," says Hanson. "Through her, you remember every little detail right down to the colors of the fish in Tahiti. She gives a very vivid picture. And in addition to her political, artistic and cultural views, she teaches people how to make borscht!" If Hanson sounds like quite the photography historian now, he admits that he knew nothing about the art when he began working with Weatherwax. "The first thing Seema asked was 'Do you like cats? OK, then we can get along,'" recalls Hanson. Weatherwax compares her vision of photographic art to the Wordsworth poem "Daffodils," in which the poet discovers a host of golden daffodils on a walk, which he later can "flash upon" while lying on the couch. "That's what pictures are like," she says. "You sometimes see something and you just know the print will look good afterwards hanging on the wall." Weston concurs, recounting how he once ran over to a dune and took a picture with the sun setting, "knowing that if I got it, it would be hanging in my living room as a lasting memory." Despite their close bond and work life, Weatherwax and Weston also maintain their own visions. Weatherwax, for instance, has rooted much of her photography in social issues, working closely with both the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which threw a 98th birthday party in her honor this August to which 300 people came. Weston, whose work mostly consists of landscapes and abstracts, opines that "the world is at once a very beautiful and ugly place. Politics is about trying to alleviate the ugliness, working to preserve beauty and right inequalities. Photography is at the other end of that spectrum, working with beauty, capturing and bringing it into the home, and sharing it with other people." But Weatherwax maintains that photography by its very nature is political--and her explanation might also be a fitting tribute to her own long overdue coming out as a photographer. "A landscape is a political statement," she says. "How much are generations after us going to see these things, if we don't try to show them, to save the beauty?"

The photography of Seema Weatherwax and Jason Weston will be on display Saturday, Nov. 15, and Sunday, Nov. 16, 11am-5pm, at 2586 Mission St. extension, Santa Cruz. [ Santa Cruz Week | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 5-12, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.