Our High-Rent Haven

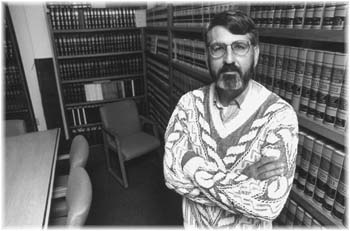

Abandon Hope: Gary McNeil, an attorney with Legal Aid who has represented tenants in disputes with landlords, says the outlook for renters is bleak.

Policymakers say renters should get used to shortages and high prices

By Traci Hukill

IN 1982, THE SANTA CRUZ Express ran an article on the local housing market in which reporter Larry Fisher sketched a sobering vignette. "Do you know what [real estate agents] are calling Santa Cruz these days?" he wrote, quoting a cigar-store patron overheard shooting the breeze with some friends. "Malibu North."

No one laughed, Fisher noted.

At the time, the housing situation in Santa Cruz was in crisis. Escalating real estate values and an increasing population had driven rental prices through the roof. Angry over a 58 percent rent hike over the previous four years (versus a fraction of that increase in wages) and fearing Santa Cruz would become another Carmel or Malibu, where only the wealthy could afford to live, groups of tenants banded together to demand that the city institute rent control. It was the third such attempt since '78. For the third time they lost at the ballot box.

In many respects, tenants today are singing a different verse of the same song. Housing is nearly impossible to find, especially in the fall when students return, and once found it's prohibitively expensive. Since 1983, rent costs have almost tripled, from $400-$650 for a two-bedroom home to $1,200-$1,500 for the same thing today. Income has risen at less than half that rate.

The cycle of blame continues as before: Townies blame students with deep parental pockets for driving up rent prices and squeezing locals out. Policymakers question the university's willingness to take responsibility for housing its own. Developers blame environmental policies for making it impossible to build. Tenants blame landlords for gouging. Landlords of properties purchased after Proposition 13 point to high taxes. Other landlords say they're only charging what the market will bear. And much as the tenants would like landlords to give them a break out of the goodness of their hearts, it probably won't happen.

In such a climate it's not surprising to hear some people grumbling about rent control again. But that probably won't happen, either. And the bleakest feature of the housing landscape is its utter lack of attractive solutions.

"Rent control has taken a bad hit statewide," says Councilmember Mike Rotkin, a one-time advocate of rent stabilization. He cites Santa Monica's plan to dismantle its rent control by the end of next year, adding, "The citizens [of Santa Cruz] have spoken three times on the issue. It would be arrogant for [the council] to pass a rent-control ordinance right now."

Voters defeated each of three attempts to enact rent control--in 1978, 1979 and 1982--by a margin exponentially greater than the one before. Then, as now, renters comprised roughly 40 percent of the local population. When Berkeley passed its rent-control ordinance in 1980, 68 percent of that city's population were renters. Besides, philosophical and practical problems with rent control abound.

Many landlords view rent control as discriminatory at worst and economically unsound at best. Says Joe Hutchins of Pacific West Realty Property Management, "If you say that rents are high and you put a cap on rents, then are wages too high? If we put caps on one piece of the market, we need to put caps on food, caps on wages, too.

"We believe in supply and demand. The reason we're having this housing crunch is there's not enough supply," he says. "If you put in rent control, my fear is that it wouldn't encourage the developers to come in and create more units for the students and other people who are now coming back to Santa Cruz."

In that scenario, vacant places would be even harder to find, and Santa Cruz would become a closed community of a different sort than Carmel or Malibu--exclusive not because it's so expensive, but because rentals just don't exist.

Of course, to people house-hunting in this fiercely competitive market, it already feels closed.

Most people agree that demand for housing is responsible for high prices and the scarcity of rentals.

U Could Be Home

ONE OBVIOUS SOURCE of the problem is the university, which houses fewer than 4,700 of its 10,000-plus students. In 1986, responding to the chronic local housing shortage, UCSC adopted a long-range plan to shelter its students. Administrators vowed to house 70 percent of the school's undergraduates, half of its graduate students, 25 percent of its faculty and half of all new staff hired from outside Santa Cruz County.

So far the university has fallen far short of making good on that promise. County Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt has a problem with that.

"Currently they are housing something less than 45 percent of their students, which is where they were when that long-range plan was adopted," she says. "They had an agreement to house all new undergraduates. That just has not happened."

UCSC housing director Jerry Walters points to a provision written into the plan, which he says takes the campus off the hook. According to the plan, the university is allowed to defer building when local vacancy rates reach 6.5 percent or when on-campus vacancy rates exceed 1 percent. He says that since the agreement was made, more housing has been available in town. He also points out that enrollment dropped for several years between 1992 and 1996.

"There was no demand," he says simply. "We had vacancies on campus. Like anyone else, we can't go around building when we have vacancies."

In fact, enrollment had only dropped by a total of 332 students between the four years Walters cites. And rental industry statistics indicate that during 1995, vacancy rates plunged to 0.6 percent, suggesting that perhaps the university should have been continuing with its plans to add housing after all.

The student housing crises of 1996 and 1997 left little doubt about that.

Regardless of whether it should have been building before now, the university has acknowledged the need for more housing and has renewed its pledge to house more students. By 2004, UCSC hopes to provide on- or off-campus housing for 2,000 more students.

The city of Santa Cruz has also decided to address the need for affordable housing. Galvanized by groups like Mercy Charities, the city has contributed to a number of affordable housing efforts, including El Centro, a downtown apartment house for the elderly. Two of the city's more prominent projects include the Neary Lagoon Cooperative, which was built in 1991 and supplies affordable housing to some 300 people, and Sycamore Street commons, a complex at Front Street and Pacific Avenue scheduled to open next February.

When full, Sycamore Street Commons will house between 200 and 300 people--but that's just not enough. According to Steve Farmer, the property supervisor in charge of the new complex, 886 applicants put in bids for 60 apartments at a sign-up event for the commons last month.

But there is a problem with building affordable housing within the city limits, Mardi Wormhoudt says, which results from attitudes toward poor people. No one wants complexes like Neary Lagoon in their neighborhoods. People are afraid of crime, squalor and the attendant

Wormhoudt finds this dirty little Santa Cruz secret appalling.

"I don't know when it became OK to make judgments about people's character from their economic circumstances," Wormhoudt fumes. "Now with the attitudes toward affordable housing, it makes me think that to be poor is to be considered lazy or somehow irresponsible."

Hopeless Homeless

EVEN IF SANTA CRUZ were to build its downtown up 10 stories and sprawl all the way up the North Coast, it still wouldn't meet the demand for housing generated by a hyperventilating Silicon Valley, where the housing shortage is just as severe. That's what some housing experts say, anyway, including Legal Aid attorney Gary McNeil.

"In some ways I think Santa Cruz has the potential to never meet its housing demands," he reflects. "It's a beautiful place to live, and it's close enough to a thriving economy. And I think we have an overcrowded housing market as it is. If you created more housing you might only be alleviating some of that problem but not accommodating real growth."

Councilmember Mike Rotkin backs McNeil up on this bleak view.

"I don't think building will honestly make much of a difference because

Rotkin cites greater forces at work, forces like a nationwide exodus from decaying urban centers. "If we could stem the tide of immigrants from other states, we might be able to stabilize the situation," he says. He also points to U.S. foreign policies that result in floods of immigrants to the U.S. "There are solutions," he finishes, "but they're not found at the local or county level."

If rent control won't pass, and the citizens won't allow growth either inside or outside the city limits, and it doesn't matter anyway because the entire region, the whole nation, even the world is out of control, then where does that leave us in 1997, 15 years after Larry Fisher overheard someone call Santa Cruz "Malibu North"?

At an impasse. And as renters and would-be renters already know, that is a hard place to be.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Robert Scheer

depreciation of their real estate.

demand is so high," he says. "We have this pressure for housing from people in Silicon Valley who have virtually limitless resources. If you doubled the number of units in Santa Cruz overnight, it wouldn't change the price of rent."

From the Oct. 23-29, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)