![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

The Seventh Sense Fashion Show struts down the runway toward a deeper understanding of human fanciness

By Mike Connor

The loincloth--now there was a garment. Simple, savage and essentially pointless; like Ted Nugent, who, while swinging from a fake vine onstage, actually sported one during the Cenozoic Era, even though our geologic era tends to favor much fancier apparel.

Some, like the mythical 19th-century Scottish occult mathematician John Kane, believe that fanciness--not reason, nor hanging vines--is what raises man above the animals.

"What reason overlooks," argues the apocryphal Kane in the liner notes to Idiot Flesh's Fancy album, "is the insatiable drive towards problem-creating, making simple situations insolubly difficult, elaborating every aspect of life beyond function, beyond beauty, beyond usefulness, and finally beyond sustainability. This unreasonable, mindless complexity is the true hallmark of our species. It is our glory and undoing."

Henry David Thoreau put it slightly differently: "We worship not the Graces, nor the Parcae, but Fashion."

Then let us pray.

Elegy for a Stone Dress

Our meditation is this: What does it mean to adorn ourselves so far past the point of practicality?

Shopping for an authority on the topic is easy: ask any artist who's ever participated in the Seventh Sense Fashion Show, the robustly creative and eclectic take on the runway ritual, which runs this weekend and next. The show is in its ninth year, so there are plenty of artists to choose from, but Trey Donovan distinguished himself last year by requiring two separate stages built especially for his piece, which included a 250-pound stone dress, and another made from gnarled sticks and leather.

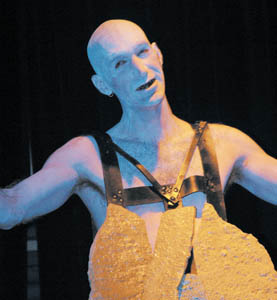

He never meant to be high-maintenance; it just so happened that the runway couldn't support the weight of the stone dress, and the stick dress snagged the curtains. Donovan's vision was to parade down the runway like everyone else (besides the aerial dancers, who hung from the rafters); he had been thinking a lot about how our way of life evolves and contrasts with the natural world, and he wanted to illustrate that with natural materials and butoh--the Japanese dance of darkness.

"Sometimes," explains Donovan, "the fashions and the things that we invent out of our natural resources tend to become abstract and cumbersome and, at their worst, actually pull us down--I had this vision of wearing a stone dress as a fashion item."

During the piece, an apocalyptic dirge by Idiot Flesh called "Chicken Little" pronounced civilization doomed, as Donovan and his models, sparsely clothed and painted a pale, ashen gray, were re-embedded not so much in natural clothes but in nature itself--a chaotic and sinister nature that menaced them with sharp sticks and the unrelenting dead weight of slate.

A casual observer of such a spectacle might think the creator of the piece is a tad cynical about our human condition.

"That's a component of the butoh," says Donovan, "that when you're in that dance, you're admonished to recognize the darkness, because it's not available to us all the time. But in that dance you can perceive the invisible darkness, and that's something that's really special to that particular form."

Moving beyond the form, Donovan insists his message was in fact a positive one.

"To me it's really kind of hopeful," says Donovan, "because, while it's tragic in a way, we're still able to perform and dance and move and enjoy parading around in our natural costumes, even when we know the natural world is going to drag us down."

Breaded Levity

Or, with a little yeast, rise back up. As is always the case, the tone of the show changes completely every couple of minutes with each new piece. Elizabeth Crow, who's worked at Emily's Bakery for almost 23 years, will use her slot to share the beauty of parchment paper--after it's been used to bake bread, which leaves abstract images cooked into the paper.

Impossibly sweet and earnest, Crow relates the everyday tragedy.

"You sell the bread and you throw the paper away," says Crow. "I always hated to throw it away because it's pretty, it's really beautiful, and I always thought to myself, 'What can I use this for?'"

Crow joins the tradition of making dresses from found objects: Film, condoms, Gap price tags, CDs, kitchen utensils, Doritos bags and now parchment paper--all have been used to create whimsical--and surprisingly coherent--dresses. It's a brand of fanciness that might have made John Kane proud, had he actually existed--simple, recycled and sustainable.

Naturally, the making of the parchment dress was not without its problems and complications--paper is not exactly the most durable fabric. But it's less problematic than, say, the dress made from a hot air balloon, or the one made from slate. Why go to all the trouble?

The most obvious answer is of course that the artists are conspiring together in a game called "Stump the Stage Manager." Lena Mason, who is stage managing the show for the fifth time this year, doesn't seem to mind.

"It has its unique challenges," says Mason. "But the biggest challenge is to make sure the costumes can maneuver to get on the runway."

Last year, the crew had to set up special riggings in the rafters for Miranda Janeschild's piece, in which aerial dancers dressed like creepy dolls unexpectedly descended to the stage at the start of the show. The element of surprise was crucial to the piece, and it could only be achieved if the performers took their positions before the audience entered the venue.

"Those poor performers had to go in before we let the audience," says Mason. "For 45 minutes they sat up there. ... We try to make it all work if we can."

"Sometimes it takes a little modification of the artists's original vision," continues Mason. "but it's definitely a collaborative process."

For artists like Donovan, the complexity of the process is part of the fun. "When I was creating these dresses," he says, "they actually injured me in several ways. They were hazardous items, and working with hazards, they teach me a lot.

"With the creation of any art object, the real work is in the process," he continues. "What ends up being on the runway might be totally different than what you aim to achieve, but during that whole process, if you're attentive to it, you get a pretty full spectrum of experiences--and therein lies the enjoyment of making art."

"It's different every time," he says. "Last year I was lucky to walk away with all my toes.

Asked why she created her piece, Crow answered more simply.

"I wanted to show people how beautiful it was--this material that usually gets thrown away."

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Fancy This

'Flintstone, You're Fired!': Santa Cruz's own Mr. Slate demonstrates the joys of bedrock couture.

Seventh Sense Fashion Show runs Oct. 15, 16, 22 and 23 at 8pm at Motion Pacific, 408 Front St., Santa Cruz. Tickets are $15, available at Chocolate, 1522 Pacific Ave., 831.420.1928. Attendees are asked to please dress formally.

From the October 12-19, 2005 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.