![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

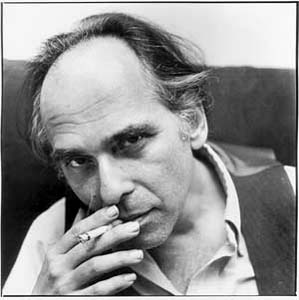

Dictatorial Doyen? Accused of holding a lock on American cartooning, Art Spiegelman is certainly the most visible comics artist of his generation.

'Maus' That Roared

Art Spiegelman changed the world of 'comix' and graphic novels and earned a place as the best-known comics artists of his generation

By Rob Pratt

ART SPIEGELMAN isn't the first comics artist to get in good with museum curators. Reserve that distinction for pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, who was really more of a painter using comics as his subject matter. And Spiegelman is certainly not the first to win a Pulitzer Prize, even though his Maus stands as the only graphic novel honored with one.

In fact, his artistic output has waned since winning the award in 1992, mostly confined to renegade cover illustrations for The New Yorker, artwork for Joseph Moncure March's poem The Wild Party and a children's book. So how did he end up at the center of a public furor two months ago when he hadn't published so much as a single pen stroke?

Quite simply, Art Spiegelman has become the best-known comics artist of his generation, a figure who earned street cred with his underground experiments and ended up mainstream thanks to a steadfast high-art sensibility.

Now a darling of the New York City media elite and a favorite on the university lecture circuit (even the State University of New York, Binghamton, where he dropped out in the late '60s, gave him an honorary doctorate after he won the Pulitzer; and he will speak this Thursday at UCSC), he's a lightning rod in the East Coast art scene.

The bolt out of the blue came in August when cartoonist Ted Rall in The Village Voice flat-out accused Spiegelman of holding a virtual lock on American cartooning, throwing choice assignments for The New Yorker and Details only to his favored clique of Baby Boomer artists and capturing the media spotlight despite work that is "flat, poorly balanced and strangely obsessed with the blue palette" and characterized by an "obsession with his seemingly favorite topic: himself." In the end, Rall concluded, Spiegelman's work is destined only to shrink in importance.

By phone from his Manhattan studio, Spiegelman seems as quick to joke as to launch into a detailed history of comics. He is truly the "doyen of the New York book, magazine, and newspaper worlds" that Rall describes. But instead of a controlling personality, he comes off as a charmer.

He requests a phone call a day ahead of time to remind him of the interview appointment, he talks enthusiastically about the work of other cartoonists he has commissioned through his consulting editorships and he's a realist about the place of fine art in a world that revolves around the almighty dollar.

"Fine art is another category of commerce, and it's dealing with smaller and smaller audiences," he says of a splintering scene in fine art and underground comics--or "comix," as he calls the form for its "co-mixing" of images and words. "Basically the whole scene seems to be just as organized around its place in a capitalist universe as anything else, which isn't to say that other concerns aren't as present.

"But something that requires effort on the part of the audience isn't as likely to find favor in this climate," he adds. "Maybe that's a consequence of how ubiquitous media is and the surfeit of information and entertainment. I think these are the issues."

FOR SPIEGELMAN, those have long been the issues. In Raw, the comix magazine he founded with his wife, Francoise Mouly, and in earlier contributions to underground comix collections (including Arcade and The Comics Review, which he edited with Bill Griffith), his work has consistently subverted the conventions of a medium generally known as mass-marketed and commercially oriented.

Instead of stories of superheroes, he writes deeply personal autobiographical tales. Good examples are Breakdowns, which explores the time Spiegelman spent in a mental hospital during his college (and LSD-dropping) years, and Prisoner on the Hell Planet, an account of his mother's suicide.

Maus and Maus II, easily his greatest commercial successes, deal with the Holocaust and repercussions from it among his family--not exactly a feel-good story even if it still commands a popular fascination. "I was as shocked as anybody that it was such a success," he says.

Spiegelman's books or "graphic novels" (although as nonfiction autobiography, they don't quite qualify as novels) hit the stands at the right moment. By the time the Pulitzer board handed him a special award, explains Joe Ferrara, owner of Santa Cruz's Atlantis Fantasyworld, underground and independent comics had reached a turning point. Long driven by artwork, comics moved more toward stories, developing intricate plots that took several editions to play out completely. And thematically, the form was wide open.

A veteran editor of comix journals, Spiegelman has helped to expand the scope of comics through his own work and by promoting the work of other adventurous artists. Once strictly the province of small-run or underground comix (which by the early '70s weren't beholden to an industry code of censorship that evolved from 1954 Congressional hearings), edgy subjects and adult themes now populate the catalogs even of big-time publishers like DC Comics.

"Comix of that time [the early '70s] came from special circumstances--the availability of high-speed web printing presses," Spiegelman says. "Specifically, they came as a response to the Vietnam War, as a response to the easy access of psychedelic substances and to a sexual loosening which allowed there to be for the first time comix not primarily anchored on selling to children. It was peers talking to peers."

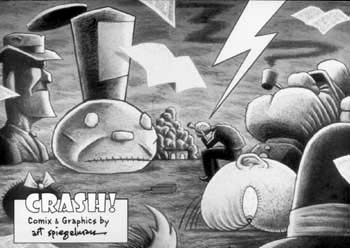

IT WAS ALSO peers inventing a new language of comix. In panels on display at UCSC's Mary Porter Sesnon Gallery as part of "Crash!," a retrospective exhibit of his work running through Nov. 21, Spiegelman's layouts range from bright-colored, cartoony illustrations to dark drawings, disjointed and off kilter in irregularly shaped frames, seemingly printed from woodcuts. If there's any consistent approach, it's in his painstaking attention to detail and striving to craft unique visual presentations for each subject he addresses.

Also evident is the time he takes to develop his ideas. The origins of Maus, first published as a graphic novel in 1986, date to Spiegelman's early-'70s experiments using animals to represent national or ethnic groups. The first published serial installment of Maus appeared in Raw in 1980 and only concluded in 1991 with the book-form publication of Maus II.

After talking to Spiegelman for only a few minutes, I realize that he engages projects both intellectually and emotionally, only really starting in on an idea when he's satisfied that it's worth a headlong effort. And he doesn't let up. Finishing a tough project, he says, is not an excuse to toss off a couple of easy ones.

"That sounds like the advice Ernie Bushmiller gave to cartoonists--he was the guy who did Nancy," he says. "'Dumb it down.'"

All of that, the intellectualism, the art-school perfectionism and the drive to make comix more than simple entertainment, has earned Spiegelman praise from artists he's edited for anthologies, for The New Yorker and for Details magazine--where he sends out cartoonists to cover current events the way a newspaper reporter would. But these qualities also provided ammunition for Rall's broadside.

It's an old story: Young upstart participates in a revolutionary underground artistic moment only to become, decades later, a mainstream figure who touches off the next underground revolution. It happens in punk rock, and it happens in punk comix.

Crash! A retrospective exhibit of Art Speigelman's comix and graphics running through November 21. The opening reception is 4-6pm Friday. Free. Gallery hours are noon to 5pm Tuesday-Sunday, and admission is free. (831.459.3606)

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Bob Adelman

SIgn and Symbol: Using a language of comics heavy with symbols and autobiographical details, Art Spiegelman stands at the forefront of a movement to elevate comics from a mass-marketed commercial form to a high-art phenomenon.

Comix 101 Art Speigelman talks about the secret language of comics in the season-opening event for UCSC Arts & Lectures, 8pm Thursday, Mainstage, Theater Arts Complex, UCSC. $10-$20. (831.459.2159)

From the October 6-13, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.