Fit to Print

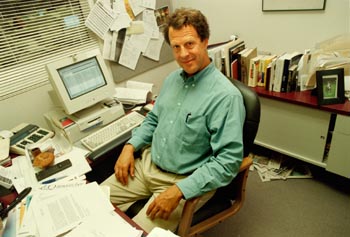

On the Hot Seat: Editor Tom Honig shepherds the Sentinel through difficult times.

Often accused of being out of touch with its readership, the Santa Cruz County Sentinel has lately been buffeted by staff turnovers, rock-bottom morale and weak leadership in its newsroom. Will it ever become a newspaper the community can be proud of?

By Kelly Luker

ON THE LAST DAY of July, an angry email was sent to more than 30 staffers in the newsroom of the Santa Cruz County Sentinel. Within days it had been copied to just about everyone in Santa Cruz with any connection to the media. The email--a resignation letter from staff writer Larry O'Hanlon to city editor Richard Cole--revealed in stark terms increasing turmoil inside the building at the corner of Cedar and Church streets. The letter was only the latest--and would not be the last--ill wind to buffet the paper, which for more than 130 years has chronicled the history and growth of Santa Cruz County.

Just days after O'Hanlon left, business reporter Steve Perez quit. Then suddenly, two weeks ago, Cole, the subject of O'Hanlon's memo, was put on administrative leave. Things came to an abrupt head last Friday, Sept. 25, when editor Tom Honig told Metro Santa Cruz that, effective at 10am that day, Cole "had submitted his resignation," which was confirmed by publisher Dave Regan. Honig would not comment on the reasons for Cole's departure.

Despite complaints about Cole, Sentinel management had until very recently seemed intent on keeping him. In an interview only three weeks before Cole left, managing editor Don Miller had called Cole "the best thing that's happened to us."

Reached by phone, Cole is mum on the reasons for his departure. "On the advice of my attorney I cannot speak immediately," he says, "but hope very much to tell very soon the whole story here." Asked why he retained legal counsel, Cole says, "I hope that it's nothing more than a precaution. I just want to be real careful and see that my rights are protected."

The staff turnover is not limited to the newsroom. Advertising director Dorothy McCoy and classified supervisor Dana Glendenning, who had been with the Sentinel 29 and 15 years, respectively, both have left recently to work for the San Jose Mercury News. Glendenning called the Sentinel "a great place to work," but says she did actively seek the position with the Mercury News.

The internal strife's open airing could hardly have come at a worse time for the paper. In the last week of June the Sentinel's corporate owner, Ottaway News Inc., ordered staff cutbacks, resulting in offers of early retirement that were accepted by 10 longtime employees. The paper's financial health has been in jeopardy for years, and the latest round of cutbacks fueled industry speculation that Ottaway may be actively seeking a buyer for the paper.

Results from a score of interviews, including those with a dozen current and former employees, suggest that the events leading up to the recent staff changes are the result of complex and long-standing institutional problems at the Sentinel which have taken their toll on employee morale, creating a workplace atmosphere that has stifled good reporters and inhibited necessary changes that might have allowed the paper to grow along with the community.

"I'm afraid the Sentinel's internal politics have begun to overshadow the paper's ability to cover the news," adds John Robinson, who worked as a reporter for the Sentinel 12 years.

Newsroom Blues

BY THE TIME he sent his blistering two-page memo, O'Hanlon had worked for the paper only eight months. "Your leadership style is a failure," O'Hanlon accused Cole. He noted that his fellow reporters "continued to produce not because of the management, but in spite of it." O'Hanlon called the paper's managers "autocratic, short-sighted and disrespectful."

"Cole's not a bad guy," explains O'Hanlon when reached by phone. "He just doesn't know how to manage."

No one--including management--disagrees with O'Hanlon's assessment that morale in the Sentinel newsroom is poor. Some trace it back to the last round of employee cutbacks less than three years ago. Others say that the newsroom lost its rudder in 1990 when popular editor John Lindsay was moved to upper management. Perhaps it was the move from a family-run business to a corporate business in 1982.

Theories abound, but whatever the reason, a common strand weaves through virtually every interview: complaints about a management that has fostered an atmosphere that breeds fear and contempt. None of the workers still employed at the Sentinel would speak for the record. That might be in part because one paper doesn't like another digging into its back yard. But as word of this story leaked out, calls and letters detailing grievances begin to suggest the opposite: a desire to vent to another paper because their own isn't listening.

"There's a culture of mismanagement," O'Hanlon observes. "Richard Cole has only accentuated what was already there." As far as O'Hanlon was concerned, the problem wasn't Cole, whose hiring was only the latest in a series of bad decisions.

Weeks after O'Hanlon and Perez left, reporter Karen Clark was moved from her Santa Cruz city beat to the Pajaro Valley bureau. Since she is arguably one of the most knowledgeable reporters of Santa Cruz city politics, her abrupt transfer caught many by surprise. In a phone interview Clark says she has no comment, but within minutes of hanging up, the phone rings.

It's Honig, who says he wants to clear up a rumor that is making its way around town. "A reporter is running around saying she's in trouble for refusing to slant her stories," Honig says. "Nothing could be further from the truth."

It did not seem a good time to tell him that he was the first person to make that allegation, but he leaves little doubt to whom he is referring.

Within days, however, at least six people related variations of the same story--that Karen Clark was "banished" to Watsonville because management wanted her to sensationalize her reporting, to slant her coverage of the Santa Cruz City Council. The tale-bearers range from politicians to agency heads to other news people in town. None had ever worked for the Sentinel.

Women in the News

AT LEAST TWO former female staffers say the paper's management has a good record in its treatment of women at the paper. Tracy Barnett worked as chief of the Pajaro Valley bureau for two years until a year ago, and is now editor of the University of Missouri School of Journalism's newspaper, The Missourian, in Columbia. She says that the paper was an equal-opportunity challenge. "I've seen men get chewed up and spit out," says Barnett.

Marybeth Varcados was features editor for eight years. When she was promoted to managing editor, she notes, "there was a concentrated effort to put women in management." She adds that until recently, the heads of both classified and advertising were women.

Maria Guara, a former Sentinel reporter who left in 1991 and now works for the San Francisco Chronicle's San Jose bureau, disagrees. One of the paper's biggest black marks, says Guara, is its failure to allow women any sustained voice in the upper echelons of management.

"Women never go anywhere there," she observes. Although several women have taken their turns in editorial positions, she says, they rarely last.

"The women do the job with no backup or no power and [the paper] makes it miserable on them," she adds. "That's been a real morale killer for the women." Guara attributes the difficulties to the Sentinel's "old boys' network."

Guara tells of the time a male reporter was hired after her, yet given a higher salary. When she went to complain, she was told that the male staffer deserved a higher salary because he had a family to support.

More recently there is some indication that management is concerned about how women have been treated in the organization.

"I never filed a sex harassment complaint," says reporter May Wong, "but management came to me with questions. That's all I'll say about that."

Power Brokers

LIKE O'HANLON'S EMAIL, the Clark rumor is an illuminating metaphor about the nature of news and those who broker it. Whether it's gossip, innuendo or straight reporting of the facts, news sculpts how we view the world, and daily papers can exercise a powerful influence, especially in small towns.

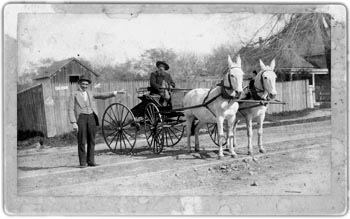

Duncan McPherson figured this out when he acquired the weekly paper Pacific Sentinel in 1864, which he renamed the Santa Cruz Sentinel. A logger who migrated here from upstate New York, McPherson spawned a publishing dynasty. The Sentinel remained in the hands of the next three generations of McPhersons until it was sold to Ottaway News Inc. in 1982. McPherson and his progeny were all conservative Republicans, and the Sentinel reflected that. Assemblymember Bruce McPherson, a moderate Republican, is the brother of Fred McPherson III, the last Sentinel publisher before the Ottaway purchase.

Duncan McPherson was a strong pro-conservationist and proponent of women's suffrage, according to local historian and author Geoffrey Dunn. Yet he also fanned the flames of anti-Chinese sentiment that spread through California in the late 19th century. The Chinese were "half-human, half-devil, rat-eating, rag-wearing, law-ignoring, Christian civilization-hating, opium-smoking, labor-degrading, entrail-sucking Celestials," wrote Duncan McPherson in an 1879 Sentinel editorial quoted by Dunn in his collection of essays on historical Santa Cruz titled Santa Cruz Is in the Heart.

Barnett wonders if that legacy has cast its pall more than a century later.

"It [the Sentinel] has never been very good at covering minorities," Barnett notes. "I tried to do that, but I ran continually into resistance from editors who [implied that] whatever happens to Mexicans in Watsonville doesn't matter much [in north county]."

Publisher Dave Regan vigorously denies the suggestion that the paper is insensitive to minorities. Regan, who came to the Sentinel as its publisher soon after the Ottaway purchase, broke into the business in 1962 as a printer and has never worked as a reporter. He has gained respect for knowing his limitations and maintaining a laissez-faire attitude with the newsroom. Regan notes that the Pajaro Valley and its largely minority customer base offers the most opportunity for circulation growth--an estimated 11,000 potential subscribers--and his paper has worked hard to take advantage of that. A weekly column titled "People of Pajaro" was introduced recently, which will be written by Pajaro Valley bureau reporter Michael Merrill.

Although the paper has still not gone online--Regan says the 1995 cutbacks derailed those plans--the Sentinel has worked hard to connect with its readers. Regan points out that a redesign has been in process for months. Known by their industry buzzwords "deeps" and "briefs," occasional in-depth articles and lots of shorter pieces will be more of the norm throughout the paper.

Page Two now carries a left-side column with one- and two-paragraph short news items.

"We're trying to be easier to read," explains the publisher. "We're respecting our readers' time."

Managing editor Don Miller also introduced the Monday Personal Technology pages, a collection of locally written and wire articles that offer fast, accessible high-tech information for readers.

Lost Opportunities

WHATEVER ITS FAULTS, most would agree that the Ottaway Sentinel is still a vast improvement over the McPherson reign.

Dave Brockmann worked at almost every position in the newsroom in his 29 years with the Sentinel until he accepted the early retirement offer in July. He recalls that Ottaway infused new technology and expertise, but more importantly, "They provided some leadership to get the news presented in a more professional way," Brockmann says.

Santa Cruz County personnel manager John Laird agrees. He's lived in Santa Cruz 30 years and served on the City Council between 1981 and 1990.

"I think the purchase with Ottaway coincided with a great improvement in the paper," he says. "It improved graphically and it improved in that its coverage was more balanced."

That may not have been the case in the decade before Ottaway's purchase. Local coverage tended to focus more on Rotary Club meetings and police blotter activity than the enormous changes affecting Santa Cruz in the '60s and '70s. It is then, many charge, that the Sentinel gradually began losing touch with a rapidly changing population.

Bookshop Santa Cruz owner and former mayor Neal Coonerty remembers the Sentinel's coverage of that era. In addition to running his downtown business for 25 years, Coonerty has kept active in political and community affairs and has had plenty of time to watch--and be watched--by the town daily.

"To its credit, the Sentinel was part of the booster club that brought in the university," he remembers. "But they were unprepared for the huge cultural change and didn't approve."

Coonerty says that when he thinks of the Sentinel, he feels more of a "sadness for lost opportunity."

"It could have been a great small-town paper," the bookstore owner observes. "There's a number of things going on that's exciting in this town and it's not reflected in the Sentinel."

Culture Wars

THE RETURN OF RICHARD COLE to Santa Cruz and the Sentinel brought him full circle. Cole made his name here during that era of unrest as one of the founders of the alternative newsweekly The Independent--one of several weekly and monthly newspapers that bloomed in the wake of this town's explosive changes during that decade. With the advent of UCSC and the social upheaval of the time, Santa Cruz rapidly moved from a sleepy, conservative retirement town to a hotbed of progressive politics.

Newspapers with names like Free Spaghetti Dinner, Sundaze and The Phoenix helped spawn the careers of several well-known local journalists. Metro Santa Cruz executive editor Dan Pulcrano, former editor Buz Bezore, present editor Michael Gant and food writer Christina Waters all worked with Cole on The Independent. So did Dunn, who is now executive director of Community Television of Santa Cruz, as well as writer Bob Johnson and cartoonists A. West and Tim Eagan.

"A lot of the alternative weeklies are here because the Sentinel wasn't reporting much of the changes," remembers Coonerty. They thrived in the wake of the Sentinel's unabashed conservativism, which championed development and bolstered anti-hippie sentiment. Cole recalls harboring a "visceral hatred" for the town daily.

"The Sentinel was clearly on the other side of the gap," Cole says. "I think both sides saw it as a cultural war."

Cole disappeared from the region for almost 18 years after selling The Independent in 1978, meanwhile building a reputation as an investigative reporter for Associated Press. When Honig offered him the job of city editor in May, Cole says he was ready to return to Santa Cruz.

Root Awakening

A HIGH-PRESSURE JOB, the city editor position requires the ability to make daily judgments about news value while juggling dozens of competing egos trying to land their stories on the front page. It's a tough job, but Cole faced extra pressure: As the sixth city editor in three years, management was counting on him to be the one to shore up sagging morale, apply a firm editorial hand and start putting more teeth in the local coverage.

And it's not just the city editor position that is in flux. As in all industries, the days of long-term employment in the newspaper business are gone. Employee turnover at the Sentinel is high. Nine newsroom staffers have left since the beginning of the year. Reporters and editors stay just long enough to discover what a complex town they have been assigned to cover.

Robinson believes that while this may work in some communities, it can't in Santa Cruz. He began his tenure when the McPhersons were still there and turnover was zero.

"It didn't matter what you thought of the McPhersons' politics," Robinson says. "They were loyal and it was good pay." But gradually under the Ottaway ownership, Robinson says, the paper began hiring less experienced reporters and salaries slipped. As a result, he noticed, "the editors and reporters didn't have the roots."

He tells of one editor who had been there two years and asked where Bonny Doon was. Barnett tells of another editor who called down to the Pajaro Valley bureau and asked if Watsonville's beaches allowed nude swimming.

Laird also noticed the staff changes.

"Pre-Ottaway, the staff seldom changed," Laird says, "but then they hired newer and younger people which helped improve the paper."

But those new reporters also don't have experience with the community. "You have to work with them to bring them up to speed," he says.

Robinson says that the Sentinel produces a "decent" paper, but adds, "it could have been great because of the talent and the amount of stories in this town.

"Whatever problems that paper has," figures Robinson, "it's from the inside."

If there was one person who walked through the Sentinel halls unscathed, it was John Lindsay. Lindsay, who began working at the Sentinel in 1961 when he was 15, is about the only subject everyone interviewed agreed upon. Several described him as the "heart and soul" of the newsroom. In an industry riddled with cynicism, competitiveness and backbiting, Lindsay was the guy that others turned to for inspiration. Like Brockmann, Lindsay took the buyout offer in July of this year.

Although he was moved down the hall in late 1990 to become the paper's general manager, it was rumored that Lindsay was the one with a steady stream of employees knocking on his door for a should to cry on after the 1995 cutbacks.

"John listened to you," remembers one former staffer. "He cared."

Generation I: Sentinel founder Duncan McPherson in 1891.

The Dow of Work

BUT THERE HAVE ALSO BEEN other factors at work. The impact of global corporate consolidation and shareholder-driven profit margins on the news gathering business has radically altered the media landscape. Less than 20 percent of the 1,500 dailies left in the country are privately owned, and the race to control the dissemination of information has speeded up. In 1983 some 50 corporations dominated the media, including print, television, movies, cable, and other forms of entertainment. By 1996, that number had dropped to 10--with names like Disney, Time Warner, Viacom, Westinghouse, Gannett and General Electric branding the majority of what consumers read, watch or hear. Fewer than 30 cities have more than one daily newspaper.

"Local news is the most expensive news," says Ben H. Bagdikian, former newsman, editor and dean of UC-Berkeley's graduate school of journalism, when interviewed by phone at his home in Berkeley. "It's produced by someone on the payroll, with a health plan." As a result, the trend--particularly in community papers--has been to rely on the cost-effective solution of wire stories.

Honig estimates the Sentinel's "news hole" has shrunk about 10 percent in the last decade. However, he believes that the paper has tried to compensate by bucking the industry trend and focusing more on local news rather than wire stories.

While the Sentinel could not escape its destiny as one more little cog in a big machine, it appears that the McPhersons chose well when it came to new owners.

"[The Ottaway News Inc. chain] generally has a better reputation than most," notes Bagdikian, "because [founder] James Ottaway had earlier expressed deep disappointment at those newspaper chains that don't give their communities good coverage and good advertising rates."

Still largely managed by the Ottaway family, the company has carved out its niche in small communities, with 19 dailies and 17 weeklies. Ottaway has a reputation as a hands-off corporation, encouraging autonomy in its newspapers.

Unfortunately, Ottaway has its own boss--Dow Jones & Co., which also owns the Wall Street Journal. Industry analysts saw a good match when Dow Jones acquired Ottaway in 1970, because both corporations valued journalism as more than a commodity. According to a February 1997 article in Fortune magazine, Dow Jones was the worst-performing stock on the Standard & Poor 500 publishing index in the decade prior to the end of 1996. More than two decades after the Ottaway purchase, Fortune reported, Dow Jones' commitment to journalistic excellence began to fade under growing pressure from angry shareholders.

In addition to its other woes, the '90s recession took a bite out of Ottaway's profits. While the rest of the Ottaway chain had rebounded by mid-decade, the Sentinel was still struggling. According to figures supplied by the Audit Bureau of Circulations, Sentinel circulation within Santa Cruz County has remained stagnant or gone down slightly since 1988, despite increases in county population. The figures suggest that the Sentinel is failing to attract new subscribers from these new residents--many of whom have moved into the county from Santa Clara County--who appear to be opting to read the paper they were reading over the hill: the San Jose Mercury News.

Figures for the first quarter of 1988 show circulation of 27,802 for the Sentinel daily edition and 30,515 for the Sunday edition within the county. The corresponding figures for the Mercury News Santa Cruz County circulation are 7,863 and 10,345. The latest figures, from the first quarter of this year, indicate a Sentinel circulation of 27,098 for the daily edition and 29,483 for Sunday--both slight declines. The Mercury News, meanwhile, has increased to 11,321 for its daily edition and 13,687 on Sundays. After a big jump between 1988 and 1991, Mercury News figures continued to climb steadily.

Ottaway demanded that Sentinel management cut costs, and in December 1995 10 employees lost their jobs--four of those in the newsroom--and a three-year wage freeze went into effect.

For a paper that had such a long history of employee loyalty, the cuts destroyed the deniability that Sentinel staffers were irreplaceable. Many responded in kind.

"I left because ... they started seeing people as disposable," Guara says. "Some of the best people stay a year and collect clips and go on."

Then, in July of this year, a second round of cuts hit the paper. Even though nationwide newspapers were averaging about a 20 percent profit margin--a rate most industries would kill for--and Ottaway averaged 22 percent, the corporation set a goal to achieve 27 percent profits. Ottaway whittled 241 jobs throughout its chain, including 10 jobs at the Sentinel, reportedly through generous buyout offers. This second shakeup in less than three years sent more reverberations through the paper.

In addition, the decreased staff size is being felt in the community.

Laird notes that he has been a Cabrillo College trustee for five years.

"In my first year there was a Sentinel reporter at every meeting," he remembers. "I don't think we've seen one since."

It's this loss of local coverage that will cause ripples throughout a community.

Bagdikian points out that our nation is unique in that so much governmental control is at the local level.

"The only staffs in the country that are trained to cover the civic bodies whenever they meet are from the newspapers," Bagdikian says.

"It's the newspapers that produce detail and background," he adds, "and there's a great loss to the community when that detail is lost."

However, the Sentinel had few options, according to publisher Dave Regan. He admits that of Ottaway's 19 dailies, the Sentinel ranked last in financial performance for 1997.

"But," Regan adds hopefully, "I expect to move up."

Asked about the rumors that Ottaway chain papers--or at least the poorest performers--have been ordered by Dow Jones to clean up their bottom lines for prospective buyers, Regan would only point out that the whole chain went into "profit margin improvement." It is perhaps worth noting that the Knight Ridder corporation owns two nearby papers, the Monterey Herald and the San Jose Mercury News.

Power Breakfast

TOM HONIG MEETS to talk over a breakfast of scrambled eggs at the Walnut Street Cafe. It's only 8am but he already looks exhausted. People warned me that Honig would try to spin me, but if he is doing so, he's a master at it. He's disarmingly easy to talk with, and we compare memories of Santa Cruz from the early '70s, when he started work at the Sentinel under the McPhersons. Honig was city editor from 1983 to 1989 and admits it's a difficult job.

At the time of our breakfast meeting, it is a month before Cole's abrupt departure from the paper. But with O'Hanlon's resignation and Clark's transfer, there is already plenty of friction surrounding the city editor. In defense of Cole, some former staffers and news people say that the Sentinel newsroom has been a scene of virtual anarchy after years with no consistent editorial supervision--a situation that would make life hell for any new editor.

One former reporter described the problem since Lindsay moved up as one of "benign management."

"I think it's like McHale's Navy," says one observer. "They just don't want a strong editor."

Honig is not surprised that Cole is meeting resistance, but wants to make it clear that the reporters are not the problem either.

"It's not that reporters were screwing up," Honig says, "it's that we weren't operating efficiently."

He's also willing to take the heat for the invisibility of women in upper management.

"That's a valid criticism," Honig says. "One of the things I take seriously is the lack of women in management--I consider it a failure on my part."

Asked how that pattern could change, Honig says, "If I knew, I would have done something."

He agrees that morale is bad and that turnover is high, the latter being a "significant problem" in how it affects news coverage--particularly the revolving chair at the city desk. He also mentions other contributing factors, such as the staff cuts of 1995 and 1998.

"I'd like to restore some fun to the newsroom," Honig says. When asked how, he shrugs. "If I knew how, I'd do it."

Asked how many of his reporters he thinks still feel the fire, Honig shifts uncomfortably. "People are all stressed," he says. "They have more to do."

Others are saying he's burned out, but Honig denies it. "Sometimes I can be emotional--I get bored or excited real easily," he says. "So I can see how someone can say I'm burned out." What Honig desperately wants is some stability in the newsroom, "so we can plan and make some goals."

The discussion recalls an earlier conversation in which Robinson noted how quiet the newsroom is. "You know a newsroom is vital when it's noisy," he says. "If that's not happening, it's that life isn't flowing through the newsroom."

The Deadline

IT'S EARLY SEPTEMBER when managing editor Don Miller and city editor Richard Cole meet with me in a Sentinel conference room next to the newsroom. The newsroom is quiet, as Robinson predicted, but it's morning--a long time from the chaos of an approaching deadline.

Cole explains O'Hanlon's departure--and other staff grumbling--as inevitable fallout from firm leadership.

"People here have not been consistently edited for a long time," says Cole. "Others don't like it."

Miller agrees that the instability of the staff and constantly changing city editor added to the problems.

"During that time," explains Miller, "people would make up their own rules."

As for Clark's transfer, Miller explains that it was nothing more than a duty rotation, something his and other papers do regularly.

"It keeps the paper fresher," he figures. Cole adds emphatically that Clark wasn't transferred out of the city beat, she was shifted into Pajaro.

"We needed a self-starter and we want our Watsonville coverage to be the best," says Cole. Like Regan, he acknowledges that the paper's growth has been "disproportionately large" in south county.

Why, then, would they drop from three to two reporters for such an important region?

Cole says it's about quality, not quantity. Miller adds that management never planned to keep three reporters there once the bureau was up and running.

Besides, he adds, "Karen's a talented reporter who will give us a lot."

Cole ponders the other charge that grew out of the Clark transfer: that he has sensationalized the news. He agrees that he is trying to "punch it up."

"I'm looking for a more aggressive approach to news coverage," Cole says. "I'd like to see a Sunday cover that's not 'soft' news."

Unfortunately, Santa Cruz may not provide the same opportunity for investigative journalism as some of the other larger regions that Cole has covered. Eyebrows were raised when the

![]()

George Sakkestad

Mr. Popularity: John Lindsay, who left in July, was a popular Sentinel editor until he was promoted out of the newsroom in 1990.

Photo courtesy of Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)