![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The Art of Living

The passing of UCSC prof Eduardo Carrillo this summer leaves behind a collective broken heart and a rich legacy of artwork

By Christina Waters

MEMORIES OF EDUARDO always begin with his smile, always huge with high spiritedness and barely able to deflect attention from his astonishing blue eyes. The smile--a permanent possibility of who he was in the world--welled up from the same spring as his immense talent. Somehow about light and color, always about sweetness and humor, that spring seemed unquenchable. Even now that he's gone, it still seems so.

Probably because Ed Carrillo--celebrated, loved, catalogued and anthologized--wore his gift so lightly. He never took it so seriously that it couldn't be suspended while he explored some moment of friendship, some spontaneous play. Part trickster god, part transcultural poet, Ed was all boy, and I wasn't the only woman who fell in love with him the minute she heard him laugh.

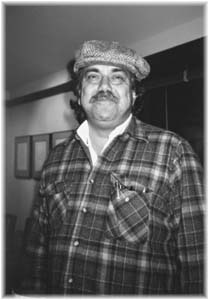

Remembering him from the bad old days, it is Eduardo of the Catalyst I meet first in memory. Eduardo of the perpetual beer, Eduardo of the plaid shirts and bohemian hats, Eduardo permanently joined at the hip to his best buddy and fellow artist/explorer, Doyle Foreman. To watch them inhaling the happy hour on Fridays you might not mark them as brilliant artists, UCSC compadres, teachers and mentors so much as two guys comparing notes on whatever scene materialized.

Ed loved to show off his schooldays friendship with fellow L.A. homeboy Ry Cooder by scoring us free tickets and backstage passes when Cooder played in town. It was about the closest thing to bragging Ed was capable of, and it felt more like hometown pride than anything else.

Ed had one of those trippy minds that could riff into the fantastic with any and every instance of storytelling. Small wonder much of his work involved murals detailing Chicano mythology and set designs for fantasy theater pieces. He always managed to dwell in multiple worlds--even on the natch.

Armed with the precocious instincts of a great child fascinated with the colors, shapes, textures and rhythm of the sensory world, Ed probed and prodded the land, here and in his beloved Baja. He'd go south there each year to putter with a favorite uncle, soak up the light of his grandmother's village, work on a never-ending building project and open himself to inspiration.

About ten years ago, a whole new window opened on his life with the meeting of Alison Keeler, who became his second wife. There had been a lot of love in Ed's life, and no one who saw them together could doubt that Alison was its crowning joy.

I was familiar with several of Ed's paintings by the time, about 12 years ago, that he invited me to visit the home of his Ben Lomond neighbor Ron Elfing. Stepping into a back living room, I found myself in a pre-Columbian equivalent of Saint Chapelle. Only instead of the light being saturated with the hues of stained glass, it was with the resonance of three enormous canvases--all talking to each other in Carrillo's muscular language of tropical sexuality and archetypal innuendo.

The air shimmered with burnt oranges, that dried-blood mahogany that was his signature, lustrous turquoise and a robust Aztec yellow. Here was evidence of his days studying in the Prado, of exploring cave paintings in Baja. Painted in the early- to mid-'80s, they were the work of an ecstatic voyager, of a man widely regarded as an inspired explorer of American painting, Hispanic and otherwise.

Before the term found currency in literature and filmmaking, Carrillo was robustly, quietly inventing magical realism. The enchantment of the everyday, the quest to capture light powered his brush. Driving the humblest experience into mythic awakenings, painting the human into countless gods, every single one of them capable of simultaneous laughter and destruction, Ed's figures--always monumental and earthy--were more sculpted than painted.

He used to say that he molded light in his figures. They bore a fundamental sense of physicality that seemed directly descended--or perhaps ascended--from muralists like Rivera and Oliveros. Solidly grounded in a world that frothed and spiraled around them like dancers in fiesta, or warriors poised to conquer some jungle enemy, his all-too-human subjects seemed to wink even in their martyrdom. Ed's Blessed Virgin drank coffee with the babes who tempted Quetzalcoatl and seduced Luis Valdez.

He always trusted his instincts, rarely worrying about critics, who invariably praised his work without quite grasping its full measure or its immeasurable fullness. Ed painted like he lived--letting go, surrendering to his appointment with the universe, trusting that moment completely. For all of us left in a world without Eduardo Carrillo, his moment was not nearly long enough.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Adios, Eduardo: The life of the late SC artist and beloved trickster Ed Carrillo will be remembered on Sunday at UCSC's Baskin Visual Arts Courtyard.

Eduardo Leonardo Carrillo died at the age of 60 on July 14 in Mexico after a brief battle with cancer. His ashes were buried in his mother's Baja village of San Ignacio. His master work was the monumental tile mural of Father Hidalgo created in L.A.'s Placita de Dolores. His work will be shown at the Joseph Chowning Galley, 1717 17th St., San Francisco, Oct. 18- Nov. 26. He will be recalled at a memorial celebration on Sunday (11am) at UCSC's Baskin Visual Arts Courtyard (459-2272).

From the Sept. 25-Oct. 1, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.