![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

In Praise of Empathy

Victor Perera as the Other-Sider

By Jordan Elgrably

THE FIRST THING I noticed about Victor Perera when we met five years ago was that he is a man of extraordinary empathy--a compassionate observer, a spiritual secularist and certainly someone who cannot be contained by ordinary boundaries. You could call him an exemplar of the Abrahamic line; Abraham, that early rebel who rejected idolatry, gave up his wealthy inheritance and set out across the desert in search of a higher truth. Abraham called himself an "Ivri"--a border crosser or "other-sider."

The story of Victor Perera's life and that of his antecedents fulfills this ancient pattern of crossing over to the other side, using free will to take fate into your own hands. An author, a progressive journalist and a much-beloved educator who has made his home in Santa Cruz and the San Francisco Bay Area for many of the past 25 years, Perera forged his identity from three cultural streams, that of Latin America and his native Guatemala; the peregrinations of Sephardic Jews kicked out of Spain some half a millennium ago; and the life he's made for himself in the United States, ever since he arrived in Brooklyn as an awkward teenager.

The son of a wealthy Guatemala City merchant, Victor emigrated to the States and fell in love with the English language. "I remember thinking of myself as a chameleon when I came here," he said in a 1995 interview with me. "I started forgetting Spanish and learned to speak Brooklynese." Although Perera's native languages were Spanish and Ladino, he has written his five books in English. His most recent book, in fact, is a brilliant memoir that tells the story of his Sephardic roots.

The Cross and the Pear Tree: A Sephardic Journey, begins with reminiscences of his mother, Tamar Nissim Perera, who spoke seven languages. Yet if one is a polyglot (and Perera followed in the family linguistic tradition), and if language is the collective memory of a people, and Sephardic Jews have many languages, what does that say about their cultural identity?

"There's a very clear answer," Victor said. "The cultural memory of the Sephardim after the Expulsion [from Spain] is a memory of Diaspora, and each of those languages ... is a reflection of that state of diaspora: state of exile, state of expatriation, the state of survival."

Victor experienced his Ivri/other-sider atavism when he married Padma Hejmadi, an East Indian he'd fallen in love with in Ann Arbor and married in New Delhi, "on an astrologically auspicious day on her Sanskrit calendar." Hejmadi's mother, it turns out, was an Aryan Brahmin "whose forebears came from Ur, in Sumeria. Ur, of course, was the birthplace of Abraham, the father of us all, a coincidence that took the kick out of our miscegenation and made us feel like long-long cousins."

In between a stint on the editorial staff of The New Yorker and publishing a novel, The Conversion, Perera taught at Vassar, and later became a familiar face on the faculties of UCSanta Cruz and UC-Berkeley. As much as he loved the attention that comes to the gifted teacher, though, Victor was ever restless, ready to pack a bag and be off.

He traveled frequently around the U.S. and in Central and South America, Europe and the Middle East. He did not always make friends, however; his early defense of Palestinian rights and reports on the deplorable situation of Sephardic and Arab Jews in Israel earned him plenty of enemies at home.

MOST OF THOSE who know Victor Perera's writing, I would venture, view him as a defender of the underdog; and indeed, for years he's written, sometimes in protest or outrage, on the fate of the indigenous peoples of Central/South America, about the lost Jews of the Southwest and Brazil (known as Crypto-Jews or Anusim), and others.

The tone of his writing is persistently empathetic, revealing his concern for human rights and equality, for bridge-building between cultural groups. Three of his books about Central America are The Last Lords of Palenque: The Lacandon Mayas of the Mexican Rain Forest (with Robert D. Bruce), Unfinished Conquest: The Guatemalan Tragedy and Rites: A Guatemalan Boyhood. Each exhibits Victor's strong connection to the land and people he writes about.

The Cross and the Pear Tree merits a second reading, for in addition to being a thoughtful meditation on history and identity that weaves together Spain and the Americas, Europe and the Middle East, what this memoir reveals is that "to be a wandering Jew teaches you tolerance of other cultures, so that you go from exile to universalism."

In several places, Victor recalls pre-Inquisition Spain's "triadic bond," in which Jews, Muslims and Christians lived such interwoven lives that they created a society rich in cross-pollination. His own work often reminds us of the complexity of identity, as we sometimes forget how close we have been to other cultures: Jews forget their debt to Muslim/Arab and Greek culture; Christians forget their debt to Jewish liturgy and civilization; and we all forget what we owe our environment, the ecology that must be sustained and about which Victor has written so eloquently.

Victor was working on a new book for Alfred Knopf, titled Of Whales and Men, when he suffered the stroke last summer that has prevented him from picking up his pen. In his Contemporary Authors entry, he provided a glimpse into his raison d'être. "I write to know better the soul within me, to see, to be illuminated. I write to find my peers, other seekers who strive to become part of a regenerative process in a time of destruction and decay." A fine writer, a persistent seeker, and above all, a true empathizer, Victor Perera has inspired many of his students, friends, colleagues and readers to cross over to the other side.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

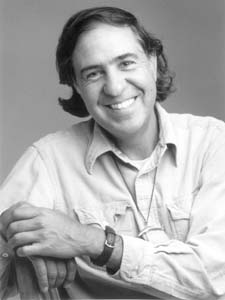

Bridge Builder: With an identity forged from three cultural streams, Victor Perera reminds us of the complexity of being.

Bridge Builder: With an identity forged from three cultural streams, Victor Perera reminds us of the complexity of being.

A longtime resident of Santa Cruz and Berkeley, author Victor Perera suffered a stroke last year which has temporarily silenced his voice. A benefit for Perera takes place in Portola Valley on Sept. 26.

Jordan Elgrably is a writer who co-founded, with Victor Perera, Ivri-NASAWI (New Association of Sephardi/Mizrahi Artists & Writers International) in 1996. The Sept. 26 concert/silent auction features vocalists Ljuba Davis, Stefani Valadez and the ensemble Za'atar and is emceed by Aileen Alfanda of KPFA. To reserve, call 650/493-0563, ext. 250, or for all details, visit www.ivri-nasawi.org.

From the September 22-29, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.