![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Kids These Days

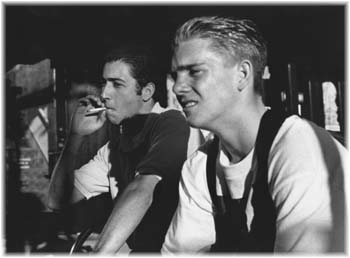

Smokescreen: Dave Chircop (left) and Aaron Zellhoefer say they think that kids are unfairly labeled as lazy or dangerous. Says Chircop, 'We're not that bad.'

Pundits and politicos are spreading fear by claiming that teenagers today are dangerous, but a careful look at the numbers shows that young people themselves are the ones under attack

By Kelly Luker

THE HEAT OF THE DAY is just beginning to break, and Justin, Aaron, Jeff and Dave are kickin' it, stretched out on the benches near Santa Cruz Coffee Roasting Company on Pacific Avenue. With their tattoos, buzzcuts and baggy pants slouched precariously below their hips, they're the typical cluster of teens which people like me try to avoid. A belief simmers, somewhere below my conscious thoughts, that these kids are trouble. They are fully capable, I am convinced, of rape or murder--or at least of caroming those damn skateboards off my vulnerable shins.

Aaron soaks up the last of the sun's rays as he gets to talking about being an object of fear. The 18-year-old neither drinks nor uses drugs, he says. He's been working steadily at the Boardwalk for the last 2 1/2 years and says he "loves it." Justin, at 24 the oldest of the bunch, graduated from San Lorenzo High and works at Subway in Scotts Valley. He knows older people are scared of him, since they shoot him frightened looks when he comes gliding down the walk on his skateboard.

Then 19-year-old Jeff chimes in, talks about looks of repulsion he gets when folks get an eyeful of his pierced nipples and tattoos. Dave adds, "they see us as lazy." The 20-year-old, a sound engineer at KSCO, has seen the angry or frightened glances toward him and his friends, but he's understanding, he says.

More understanding than I am--and a lot of frightened folks my age. I had a gut-reaction that told me they were dangerous.

Where did that come from?

It used to be a simple case of old-fart disapproval. People over 40 have never much cared for the way kids dress or for their music--be it Elvis Presley or Old Dirty Bastard. And each generation is quick to vilify the following one's morals and manners.

But now teenagers scare the holy hell out of their elders. If the news reports can be trusted (and why shouldn't they?), our society is being held hostage by people who can't even cast a vote. "Crime really is down, but teenagers are more violent than ever," screams a Newsweek headline. People magazine features a collage of murdering teens, accompanied by the query, "Kids Without a Conscience?" Helmet-haired political pundit Arianna Huffington warns of the "rise of the teenage superpredators" in her weekly column.

In response, the peace and love generation--my crowd--seems to have declared war on its young. Curfews are rolling through cities and counties--San Jose ordered an 11pm curfew on teens three years ago, Santa Cruz County's went into effect last year, and Surf City joined the ranks in August by banning kids from being out late at night.

Anti-loitering ordinances are also being beefed up, more schools are drafting dress codes, and when all else fails, youthful offenders are subjected to less-than-youthful punishments. Out of 50 states, 47 have enacted harsher penalties for teen criminals, ranging from requiring that 10-year-old lawbreakers be held in high-security detention centers to requiring criminal trials for 14-year-old murderers.

Somewhere along the line, intergenerational intolerance turned into a full- scale jihad on kids. And until we examine the seeds of our fear, there is no truce in sight.

Revolting Youth

BLAMING TEENAGERS for the world's ills is a relatively new phenomenon. But then, so are teenagers. In the agrarian society that existed until a few hundred years ago, there wasn't much of a break between toddlers and grown-ups, given that kids routinely began marrying, having babies and working at an early age. It's only been a handful of generations that have had the fun of saying, usually accompanied by a disgusted sigh, "Kids these days."

As social historian John Gillis, a Rutgers University professor who wrote Youth and History, explains, "Prior to the 19th century, [the concept of] 'youth' ran from childhood to the 20s. It wasn't until the onset of universal schooling that there was a construction of this thing called adolescence."

It only took a handful of generations to move from the Industrial Revolution to kids in revolution--out to destroy the fabric of society with sex, drugs and rock & roll. But kids these days are not content to just tweak societal norms. They are lethal killing machines--just ask former presidential candidate Bob Dole, whose platform in the 1996 race contained a plank calling for a crackdown on "violent young criminals."

"Unless something is done soon," the panicked candidate forecast in one of his campaign speeches, "some of today's newborns will become tomorrow's super-predators--merciless criminals capable of committing the most vicious of acts for the most trivial of reasons."

Quick to quote Department of Justice and FBI statistics that point to skyrocketing homicide rates and rising violent crime rates among the under-18 age group, politicos have breathlessly decried a whole generation circling the moral drain. And the statistics they choose to quote about young criminals can be terrifying:

Princeton professor John DiIulio thinks those numbers are merely the beginning. In a research paper released in 1996, DiIulio projected a future storm of juvenile violence. Coining the shibboleth "juvenile superpredator," DiIulio's research predicted 270,000 more of these young monsters terrorizing the streets by the year 2010.

Politicians made the most of DiIulio's dire warnings. Gov. Pete Wilson leapt on the bandwagon, pushing for legislation that would shift the juvenile justice system's focus from rehabilitation to punishment. Newspapers like the San Jose Mercury News ran introspective pieces with headlines like "Society Grasping at Ways to Stem Tide of Youth Crime," then tossed in a few local "youth-gone-amok" anecdotes for good measure.

The combined effect of media, academics and politicians stoking each others' anxieties has been to create a moral panic about our kids. And, as Gillis points out, moral panics about teens have surfaced periodically for the past century.

"The word 'hooligan' comes from a turn-of-the-century term for young male workers in Britain--the press had a field day with that one," Gillis chortles.

But this moral panic goes beyond banning comic books, like they did in the '50s, or publicly burning Beatles records, a popular pastime in the '60s. This time, it hungers for much more lethal vengeance: A 1994 Gallup Poll revealed that 60 percent of Americans now favor the death penalty for children convicted of murder.

Mike Males, author of Scapegoat Generation: America's War on Adolescents, agrees that there is a problem, but says it is not what the media hypes it to be.

Males believes that the young are not wreaking havoc on us, but that we are systematically waging war on our children.

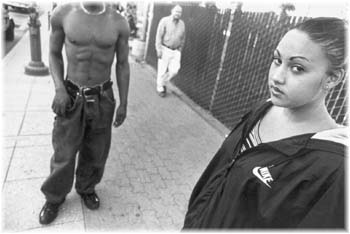

Teenage Waistland: Fourteen-year-old Shannon Nix (foreground) and her friend, 19-year-old Dorian Wesson (background), hang out on Pacific Avenue, a poplular meeting place for area teens.

Children's Crusade

'THERE'S ALWAYS BEEN antagonism between generations," Males says. "But what we're seeing now is an economic and social attack on our kids that goes way beyond intergenerational conflict." Armed with disturbing data, Males makes a convincing case that, through social and private policy, the Baby Boomers are condemning future generations to poverty and despair. Although the U.S. is the wealthiest nation in the world, it also has the highest child-poverty rates.

In the last two decades, child poverty rose by 60 percent, affecting one out of four children under 6. During the same period, poverty among adults over 40 decreased.

"America's level of adult selfishness is found in no other Western country," Males writes.

It is poverty--not youth--that breeds violence, teen pregnancy and drug abuse, he believes.

In their haste to shove through more anti-kid laws and ordinances, he says, state and local politicians manage to avoid the hard work of studying the reams of research shoved in their in-basket. It is convenient to forget that statistics, particularly involving a construct with as many variables as crime, lend themselves to selective slicing and dicing. Although it is the first thing reporters learn--never trust the numbers--they fall victim to research results that yield sexy headlines rather than doing the math--a task more feared than an encounter with the tiny superpredators themselves.

If the politicos and news hacks did run the numbers, a small detail might leap out: The "epidemic" of juvenile crime doesn't exist.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the overall arrest rate for teens has remained relatively constant for the past 30 years. Some areas of teen crime do show a frightening climb, pointing to a definite problem. But again, it may not be the problem we keep calling it.

Franklin Zimring is a professor of law at UC-Berkeley and has spent the last two decades researching youth, crime and the law. He notes that fluctuations in crime rates, although often not understood, make for great political fodder. He contends that since adult crime has been steadily decreasing for several years, someone has to step up to take the fall. Teenagers, he says, have been targeted by politicians to focus fear and motivate voters.

Zimring has researched DiIulio's work, and finds that blanket prediction of superpredators is full of holes. DiIulio's oft-quoted number of 270,000 superpredators, he says, did not accurately figure ages. So the year 2010, he says, will find us terrorized by "desperadoes in diapers," 4-, 5- and 6-year-olds which were inadvertently included with the teens.

Zimring points out what he says is faulty logic behind other seemingly frightening statistics. Assault arrests, he says, have increased because police reclassified what was once seen as "boys-will-be-boys" behavior.

"When police take fights more seriously, then more fights are going to result in arrests," Zimring says. "What looks like a crime wave is the police saying, 'Let's take this seriously.' This is not a change in kids' behavior, but a change in police behavior."

The increase in murders, according to Zimring, results more from the increased availability of guns than from a change in young people's morality.

"It's the instruments that are changing, not the kids," he says. "It was a change in the hardware, not the software." Zimring is quick to agree that there is indeed a serious problem--that we are turning to lethal ways in this culture to resolve our conflicts. The teen years, particularly for boys, are a time traditionally riddled with fighting and aggressive behavior.

"But adult weapons have trickled down," he says. "And when you mix adult weapons with teen patterns of violence, watch out."

Finally, a good look at the stats would also show that it is not we who must be protected from these so-called little killers, but kids who must be protected from each other--and from us. Less than 1 percent of crime victims over the age of 64 fall victim to minors. But 75 percent of juvenile homicide victims died at the hands of an adult.

The danger is not for people like me walking by kids like Justin and Aaron. The numbers are in my favor. It is the Justins, the Aarons and their younger sisters and brothers who face a deadly risk from adults, and sadly, adults they know--parents and relatives.

Remembering When

IT IS A WARM SUMMER DAY in the late '60s, and I board a bus headed down Fulton Street in San Francisco after having spent the afternoon hanging out at Golden Gate Park. I'm dressed in the uniform of the day--an antique tablecloth stitched into a mini-dress, bare feet and long blonde hair tied back with a headband. As I put my coins in the change box and move toward a seat, my eyes meet and lock with an old lady who glares back at me. Disgust is written across her face and she does not look away. Five, 10, 15 minutes the bus rolls along, with neither she nor I saying anything. Every time I glance at her, she is still looking at me, still frowning. Finally, we get to my stop, and as I get up and move toward the front door, the old lady can't hold back her feelings any more. She utters a curse and spits at me.

I swore I would never judge kids like I was judged--and condemned. I didn't realize that intolerance gradually works its way into the fold over the years, so subtle a presence that, given a steady diet of half-baked stats and warmed-over sound bites, it would ignite into a stampeding panic.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

From the Sept. 18-24, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.