![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Water Tortured

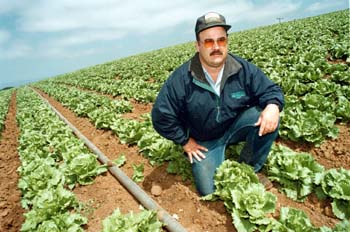

Tough Row to Hoe: Surveying rows of thirsty lettuce plants, longtime Watsonville farmer Dick Peixoto is in the forefront of those who question the wisdom of building a pipeline to provide more water to the Pajaro Valley.

With talk of a Pajaro Valley water emergency, the water management agency is beefing up conservation programs. But skeptics say the effort is just a way to push for water imports

By Mary Spicuzza

DICK PEIXOTO'S PICKUP truck whips up a cloud of dust as we pull out of his office's graveled parking lot and onto bustling Riverside Drive. The busy farmer seems to know every side road and every fieldworker we pass while driving into the Springfield Terrace area of north Monterey County.

"When I was a kid this was all 100 percent artichokes and sprouts," Peixoto says, peering out at the fields from under his baseball cap. "Now it's all going to lettuce and strawberries. Lotta strawberries."

Peixoto, a 25-year veteran farmer who was born and raised in Watsonville, says he's been driving along these roads since he was 8 years old. It was then that he started going on business calls with his dad, a fertilizer salesman.

He slows his truck and pulls onto the brown earth lining a luscious batch of strawberries.

"What I can't understand is, if the water shortage and saltwater intrusion is as bad as they say it is, why is everybody rushing to the coast to put berries out here?" Peixoto says.

I look out over the neat green rows, dotted with crimson strawberries, which stretch from the sea to rolling hills on the horizon. Using more water per acre than any crop in the valley, except raspberries, the profitable berries are also extremely sensitive to saltwater. Seawater seeping into south county aquifers threatens more crops every year, especially in the Springfield area, according to Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency statistics.

Surrounded by the thriving fields, I remind myself this land may soon be in an official state of emergency--that is, if the county Board of Supervisors decides at its Oct. 5 meeting that the water agency has failed to clean up its act. In June, supervisors tore into agency policies, accusing staffers of neglecting water conservation and local supply projects.

At that time, supervisors considered declaring a water emergency, but decided to give the agency a chance to prove itself. For years critics have accused the agency of dragging its feet on local water solutions, setting its sights instead on a $134 million pipeline project that would import water from the San Luis Reservoir, near Los Banos.

Drops in the Bucket

WATER AGENCY staffers and board members seem incredibly upbeat for people who so recently took a verbal lashing from county supervisors. Agency general manager Charles McNiesh and Doug Coty, water programs coordinator, are cordial hosts as we board an expansive bus bound for a three-hour tour of south county conservation demonstration projects.

During the field trip, Jeff Rosendale of Sierra Azul Nursery reports cutting his water use in half during preliminary tests. Peixoto, one of Pajaro's major farmers, says he hopes his new drip-tape irrigation will reduce groundwater pumping by 20 percent.

Reboarding the bus after a stop at strawberry grower Will Garroutte's weather station experiment, McNiesh says the agency is excited about voluntary water-saving measures. But he believes that mandatory conservation regulations would be counterproductive, adding that cooperating with farmers is better than strict rationing policies.

When asked about local water supply projects, McNiesh says that the agency is considering them. But he adds that studies repeatedly find such projects to be expensive and unable to provide the amount of water needed to solve Pajaro's water woes. Agency consultants now estimate the region's overpumping of groundwater--known as overdraft--at 34,000 acre-feet per year. An acre-foot is the amount of water that would cover an acre of land a foot deep, or about 326,000 gallons.

The models also indicate that 9,000 acre-feet of seawater seeps into south county wells each year. (In comparison, the city of Santa Cruz's Loch Lomond Reservoir holds only 8,600 acre-feet.)

But critics, like Watsonville water watchdog Doug McKinney, question the objectivity of the agency's studies.

"I will fold up my tent and crawl away into the night if anyone can ever show me a scientific study that was done by a reputable person saying seawater intrusion is what they say it is," McKinney says. Both he and Peixoto rallied to pass Measure D, which was approved by 58 percent of Pajaro Valley voters in July 1998. The measure placed a 10-year moratorium on pipeline construction and froze water use charges, known as augmentation fees, at $50 per acre-foot.

They called their group NOPE--No Overpriced Pipeline Ever.

McKinney, a longtime Watsonville resident, admits that he isn't an engineer or hydrologist--but the retired gadfly has earned quite a reputation by jumping to the front lines of the water wars. McKinney believes consultants' numbers are skewed to make it look like local solutions aren't enough.

"They're creating a monster to make things look gloomier and doomier," McKinney says. "It all comes down to an 'S' with two lines through it."

Lawyer Richard Hendry, who helped create the water management agency in 1983, agrees that the agency has exaggerated the overdraft problem in order to push imported water as the solution. He points to studies indicating that

In June county supervisors joined with those questioning the agency's interest in local solutions.

"The lack of commitment to conservation is shocking to me," county Supervisor Mardi Wormhoudt says. "Why the intense aversion to ordinances and regulation? As a governmental entity, I don't look at regulation as confrontational or hostile. It is something to protect all people from the abuses of individuals."

Paying the Piper

SUNCREST NURSERIES general manager Jim Marshall leads the conservation tour past a dry basin with a patch of cattails at the center. "This is the Rose Reservoir," he says. "There are people who remember coming here to swim. We think it could hold at least 20 acre-feet of water."

Learn from Cassandra predictions.

Later McNiesh explains that farmers often don't understand the environmental aspects of water storage, especially when dams and redirecting rivers are involved. Of 40 possible local water supply and storage projects, the agency found only three sites feasible--College Lake, Murphy Crossing and Harkins Slough. McNiesh hopes the agency can begin constructing pumping and filtration facilities at Harkins Slough next year, but has had to put the other two projects on hold because of the Coastal Commission's concerns.

In 1984 McNiesh, then a soil sciences student, worked on a Pajaro Valley irrigation study which found that local waters couldn't meet south county's growing agricultural needs.

He says, "Our conclusion was really the same that our agency has today: that, yes, conservation is important, but that in itself is just not enough."

State agencies labeled the region overdrafted in 1978, and farmers first noticed saltwater intrusion in the Springfield and Aromas regions in the 1950s. Still the trend toward high-water-using crops continues.

Farmers use about 80 percent of the Pajaro Valley's water, but it's important not only for agriculture. Water equals big money for engineers, consultants and developers.

Go With the Flow

'IN THE WEST, it is said water flows uphill toward money," Marc Reisner writes in Cadillac Desert. "Today, the Central Valley Project is still the most mind-boggling public works project on five continents. . . . such projects have brought into production more farmland than they had water to supply."

Besides unfulfilled half-promises of water, the behemoth Central Valley Project has created a market in intercity water dealing. For example, when Santa Barbara doesn't use all the water it has requested during any given year, it can sell the excess to other cities.

McKinney, a critic of statewide water projects, likes to point to the town of Solvang as an example of a pipeline gone awry. Solvang City Council members decided to hook up to the Central Coast Aqueduct Project, planned by the Pajaro agency's consultant Lyndel Melton and his former employer, Montgomery Watson. When council members decided it had been ill-advised, they tried to break Solvang's contract but lost in court--and ended up $60 million in debt.

McNiesh says he's not sure why pipeline opponents constantly cite Solvang's legal battles.

"It has nothing to do with us here," he insists.

Peixoto worries that small farmers, many of whom rent rather than own their land, will end up paying for a pipeline that benefits coastal property owners and big-money consulting firms. Landowners could farm their fields or sell it to developers, now busily seeking ways to profit from the Silicon Valley boom. Technically, the pipeline waters could only be used for agriculture, but Measure D proponents argue that once in place, the pipeline could fuel farmland annexations.

"Adequate water supply is something that land never had before. But should a little farmer in Corralitos have to pay for it?" Peixoto asks.

Anyone need look no further than Los Angeles for evidence of farmers footing the bill for urban development. There, water commissioner William Mulholland had no trouble cultivating L.A. on water drained from Owens Valley's groundwater--even manufacturing a water crisis in order to justify it.

"Fortunes have risen and fallen on water politics," says Wormhoudt.

Water Under the Bridge

RAYMOND AMRHEIN eases into his old wooden chair, which is surrounded by packing crates full of files. After nearly 50 years as a practicing lawyer in Watsonville, he says he's finally ready to retire.

Behind AmRhein's chair hang hints of the valley's past--frames holding labels for Pajaro Valley and Sunkist brand apples. Crops using drastically more water have almost completely replaced apples as south county's staple crops.

AmRhein worked with Richard Hendry and others on an unpaid advisory committee to draft plans for the water management agency. They hoped the agency could complete objective scientific studies, rather than politically motivated ones. But AmRhein says that even before its inception, the agency became tangled in politics.

The committee wanted the public to elect water board members, not allow politicians to appoint them. In addition, rather than following AmRhein's boundary suggestions, politicians stretched the southern boundary to include part of Monterey County--including saltwater-intruded Springfield. AmRhein says that these boundaries have exacerbated south county water woes.

AmRhein isn't surprised that county supervisors may bypass the agency, which he says was founded in chaos.

"We never finished planning the agency," AmRhein says.

He explains that then-Assemblyman Henry Mello took the agency's draft charter to the California Legislature before the planning committee could complete its project. At the same time, the committee was scrambling to establish the funding structure for the agency. They had established augmentation fees, but hadn't yet spelled out important guidelines water agencies must meet to collect fees--like yearly water metering and specific uses for the money. But the draft charter did say that the fees could only go toward capturing, storing and treating district water.

"Those fees were meant for recovering local water," AmRhein says. "They were never meant for a pipeline."

Banzai Pipeline

TRYING TO CHANGE its conservation-wary reputation, the agency is currently distributing a water use survey to local farmers. But some members of the agency's new conservation committee want to know whether the agency is sincere or just after good P.R.

Solutions to faulty water systems.

"The agency is a regulatory agency, but considers it a violation of privacy to regulate," says Kate Hallward, a United Farm Workers researcher and committee member.

On Oct. 5, the supervisors will assess whether the agency has made firm steps toward local solutions. NOPE member McKinney believes the conservation effort is a halfhearted smoke screen, and the agency is still concentrating on its efforts to repeal Measure D in this spring's election. He and Peixoto say that despite the voters' decision, the agency's tunnel vision is fixed on a pipeline.

"Once we decide we can't live within our water limit, we become a cog in the gigantic, powerful California Water Project. At that point we're at the mercy of powerful political interests," says Christine Lyons of Watsonville Wetlands Watch. "The issue of local control will shape the future of this valley."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

Water Is His World: Standing at the Harkins Slough pumping station, Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency general manager Charles McNiesh believes local solutions

will not be enough to solve the valley's water woes.

7 million acre-feet exists in the basin, although McNiesh counters that this water is largely unusable for irrigation.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the September 15-22, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.