![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Body and Soul

The Monterey Jazz Festival returns with three generations of talent and creativity

By Peter Koht

The stage at the Monterey Jazz Festival has become a nexus of jazz history. Over the course of the 48 years that the festival has been in existence, the humble planks of the Monterey Fairgrounds stage have been trodden upon by the finest jazz musicians ever to step to a set of changes.

Founded by Jimmy Lyons, a tremendously creative saxophonist and a member of the Cecil Taylor Unit, the Monterey Jazz Festival has attracted the top tier of working musicians since its opening night. In addition to appearances by the Modern Jazz Quartet and Billie Holiday, that first evening also featured what would become a salient feature of the festival by the sea: the convergence of generations.

The irrepressible trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie served as the festival's first master of ceremonies. In a moment of sublime showmanship and genuine appreciation, he welcomed Louis Armstrong to the stage by dropping down on his knees and proffering a kiss to Satchmo's hand. It was a crystallized example of one generation paying homage to the one that preceded it, a legacy that continues to this day.

"It's a big family affair," says drummer Matt Wilson, who will be performing at this year's festival with pianist Denny Zeitlin's group. "When I go to these festivals, it takes an hour to play the set and two hours to say hey to everyone."

Wilson reserves particular respect for those musicians whose tenure is the longest, as they are the living repository of all the best stories about a life spent chasing the changes. "Just to be around those guys," Wilson continues, "is an inspiration. I firmly believe in [formal] education, but you got to go to the sources."

This year, the festival will continue to unite the best in emerging talent with the generations who led the way. Among the former are French-American chanteuse Madeline Peyroux, the avant-awesome Lounge Art Ensemble and Mike Watt's punk jazz outfit Banyan. Representing the old school are the likes of guitarist John Scofield, crooner Tony Bennett and one of the world's greatest tenor saxophone players: Sonny Rollins. In the words of Wilson, "of all the people in jazz, Sonny Rollins is high on the pedestal of legends."

Search for Peace

"That's a pretty tall order," Rollins says with his customary humbleness over the phone from his home in upstate New York, just days after his 75th birthday, "I don't want to sound too grandiose or that I can represent jazz [in its entirety]. But as one of few remaining people from that period [the heyday of bebop during the '40s and '50s], I want to represent myself and the kind of musicians from that period, so that people who are new to the music can say, 'These people were good; they aren't just a bunch of old moldy figs.'"

Born in Harlem in 1930, Rollins was an adolescent acquaintance of both Thelonious Monk and Jackie McLean. Before he reached his 20th birthday, he was in Miles Davis' band and has shared both the stage and the studio with such luminaries as John Coltrane, Max Roach and Clifford Brown. Rather than spending his golden years traipsing down memory lane, Rollins is a focused and introspective musician whose main goal has always been to "make sure that I sound good, which is a hard enough job in itself."

He has very little to worry about. His latest release, Without a Song, was recorded live four days after 9/11 and contains the kind of melancholy but hopeful music that cements Rollins' reputation as a formidable performer. He's also a deft social commentator. "Music is about transcendental things; it is about where we want to be, not where we are. Music will always break down barriers because it is not about things on this earth."

Rollins knows more than his fair share about the transcendent nature of the universe. Throughout his career, most famously in 1959�61 and again in 1966�72, he removed himself from the hustle and noise of a life onstage and retreated into his own paradigm of study, practice and meditation. While many professional musicians either disdain or avoid practice, it is something that Rollins still relishes.

"I am always happy to be practicing. Period," Rollins says with a chuckle. "I enjoy just playing my horn and going into the type of meditation that playing involves. It puts me mentally in a place that is always transcendent and above real life. I love playing just for myself. It's a great experience."

But sharing that experience live is what really excites Rollins. Though he just turned 75 last week, his love of performing hasn't diminished in the slightest. "Playing in public engenders new paths in your brain that you won't get playing alone. In other words, I can learn something playing in public in five seconds. If I was learning it in private, it might take me three months to get."

Discussing the generational aspects of the development of jazz with Rollins is a unique experience. Even when asking about the hardest issues, like the role that racism has played in the historical acceptance of jazz, he is gracious, thoughtful and insightful. Wisely taking the long view, Rollins recognizes that similar processes are now affecting the acceptance of hip-hop by white America.

"As the years went by and jazz got more popular and social conditions changed, you were able to have jazz as a topic introduced into the music curriculum in universities," Rollins says. "I think that one thing that hip-hop and jazz have in common is that they are both coming out of the minority subculture and we've faced some of the same problems. They are attacked in different ways . . . but they are a minority in a majority culture, so they are unfortunately discriminated against by the larger portion of the majority community."

After experiencing the heady power that massive success can engender, Rollins knows firsthand the temptations that young musicians might face as they rise through the ranks of the music industry.

"When I was young I thought that I wanted a big car and thought that it was all about being famous and having a lot of fine women and all that consumer stuff," he says, his voice earnestly inflected. "The things that I have found out through my life that really mean something have nothing to do with the accumulation of goods. We have to be vigilant about our own souls and make sure that we are doing what we want to do. That is the only place where real happiness comes from."

Unchain My Heart

Like Rollins, John Scofield is another musician whose long career has been marked by breaking stereotypes and diving deeply into the spiritual aspects of improvised music. Scofield, who first came to prominence in the jazz fusion movement of the '70s, was lucky enough to have been taken under the wings of both Miles Davis and Charles Mingus early in his career, and now he is returning the favor by collaborating with three different groups that include younger musicians who have yet to reach a larger audience.

Following a Friday performance with his Überjam Band--whose groove-infused ranks include Avi Bortnick on rhythm guitar and samples, and drummer Adam Deitch--Scofield will also bring his tribute to Ray Charles to the Festival Arena on Saturday night.

Scofield has nothing but praise for his new soul band, which includes rising stars Gary Versace on organ, John Benitez on bass, Steve Hass on drums and Meyer Statham on both trombone and vocals. According to their leader, the whole group is made up of "young guys from New York who're really killing it. Meyer's a great find. He's been playing in bar bands up in Boston. He's this super R&B style gospel singer." Yet all praise for youth aside, Scofield is especially anticipating his onstage collaboration with "the great diva of soul," Mavis Staples.

"I've been listening to her music with the Staple Singers going back in the '60s [when] they first came on the scene and I heard them on the radio when I was a kid. I heard her live at the Monterey Jazz Festival when I played there in 1998," Scofield says, recalling his only performance at the festival to date. "The Staple Singers were there, but the first time that I met her was when we recorded 'I Can't Stop Loving You' together [for Scofield's recently released Ray Charles tribute album]."

On Sunday, Scofield's third and final show will reunite with one of his oldest friends and mentors, electric bassist Steve Swallow. These two buddies will be joined by Scofield's "favorite of the current jazz drummers," Bill Stewart, to complete the lineup of the famed John Scofield Trio.

While always looking musically forward, Scofield is not above reminiscing about his first run-in with Swallow back in Boston during the halcyon days of the Ford Administration. "Steve came to teach at Berklee. I had stopped going to school there, but I was still on the scene. This was during the early '70s and I was just a kid. He was really great to me."

Scofield has nothing but praise for his unconventional mentor, whose pick-based attack on the electric bass separates him from the vast majority of working jazz bassists. "I think that he is one of the most unique voices in all of jazz. Nobody sounds like him."

No matter what the situation, whether hard bop, soul covers or the loosest of jams, Scofield's chameleonlike approach to the guitar is among the most versatile and compelling in all of jazz, one that is equal parts texture and melody. "I think I try to play to fit the music," he says in a feat of massive understatement. "It's not so conscious really, because you're improvising and you are thinking about what is right with the song, no matter what the context."

Minuteman

Context is a little bit more complicated for the group Banyan to establish. Consisting of former Minuteman bassist Mike Watt, former Jane's Addiction drummer Stephen Perkins, guitarist Nels Cline and trumpeter Memphis Willie, the experimental improv group's performances also feature painter Norton Wisdom creating live art behind the band as they freely improvise.

"The idea of improvising, it takes a lot of listening," Watt says, calling from his home in San Pedro. "This group was Steven Perkins' brainchild. He is kind of the leader. He even sets up in front of us, which is kind of weird. He is the band leader, but he ain't yelling at us or anything."

Finding this group of musicians playing at the Monterey Jazz Festival isn't at all surprising given the adventurous spirit that has always played a part in the development of the genre. "Raymond Pettibon [L.A. punk artist] turned me on to the old beboppers," Watt says when asked about his connections to the jazz world. "It was so intense to listen to, like, Albert Ayler or Sonny Rollins. When I first heard them I thought that they were doing punk. There are a lot of parallels between punk rock and jazz; they are both really small scenes that are filled with really adventurous guys."

Lamenting some of the "imitation" and "ossification" that plagues some elements of contemporary jazz, Watt wisely remarks that "Thelonious Monk couldn't win the Thelonious Monk Competition. Guys like him were really out on the edge. You just got to break the glass and be creative."

Goodbye, Pork Pie Hat

It might be the salt air or the presence of so many jazz luminaries in one place, but the creative glass tends to fly during the 72 hours that the Monterey County Fairgrounds become the focal point of the jazz universe each September. Each year, the festival grows in scope and quality. While it's unfortunate that so many jazz musicians have gone off to the great gig in the sky, their ranks have been replenished by such talents as Festival Artist in Residence Branford Marsalis and Commission Artist Carla Bley. Along with hundreds of other musicians who will exhibit their musical prowess on the grounds, their work--along with that of the festival organizers--will help ensure that the legacy of Armstrong, Gillespie and Rollins continues far into the future.

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Okay, Sonny, We Give Up: A picture so damned sweet, it defies snarky captioning.

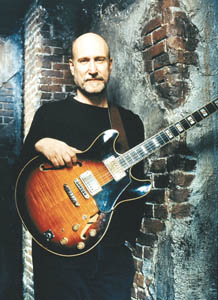

Wall the Young Dudes: John Scofield will take some 'young guys from New York who are really killing it' under his wing during his first of three performances at this year's festival. performances.

'Abandon All Hope? No!': The unstoppable Mike Watt will go where no punk icon has gone before when his group Banyan makes its Monterey Jazz Festival debut this year.

The Monterey Jazz Festival runs Sept. 16�18 at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, 2004 Fairground Road, Monterey. Arena tickets are sold out; grounds tickets/$30 Friday, $40 Saturday and Sunday; weekend pass/$95. For more info call 925.275.9255 or visit www.montereyjazzfestival.org.

From the September 14-21, 2005 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.