![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Water to Whine

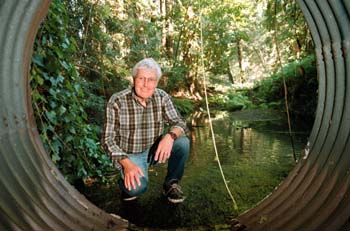

Making His Water Mark: Hydrologist Bob Curry, shown here in a branch of Soquel Creek, works to protect aquifers and stream flows.

The Big One might not be an earthquake after all--it may be a crippling drought

by Rachel Ann Goodman

When the 88,000 customers of the Santa Cruz water district awoke on the morning of Aug. 19, it was as if the Y2K bug had struck early. Either through accident or poor contingency planning, something had gone wrong at the district's Graham Hill treatment plant which had resulted in a "bad water quality reading." Invoking the magic word, rationing, the water department mounted a major PR effort to get people to cut back usage by 50 percent. The story quickly topped the headlines and the TV news, which played the temporary emergency as a kind of surprise drop-and-cover drill, a dry run for the drought equivalent of The Big One.

If it was a test, we flunked.

The best Santa Cruzans could do during the first 24 hours was a 33 percent cutback. Over the weekend, as the sense of urgency faded, that dropped to a mere 14 percent. The emergency even had to be extended a day because of the lack of cooperation. But while it did succeed briefly in drawing attention to the problem, it may also have lured us into a false sense of security.

With drought as inevitable as earthquakes in California--if there were a Richter scale for droughts, California would be about due for a 7.0--the inconvenience of a one-third cutback over three days will prove to be nothing compared to the real thing.

A dry spell such as the drought of 1976-1978, for instance, would likely require severe use restrictions and cutbacks in consumption of up to 50 percent for an extended period--especially with county groundwater levels in many parts of the county already dangerously low or threatened by saltwater intrusion.

Santa Cruz City water chief Bill Kocher had been pressing for additional sources of water since before the emergency.

"Developing new supplies, which are considered necessary to meet future needs, must be carefully planned to take in environmental impact, an assessment of how customer demand can be lowered through conservation programs, and the cost to you, the rate payer," reads a water department brochure.

With the politics of water inextricably linked to development throughout California history, the struggle over water policy and drought contingency planning will be monumental. Among the various options--conservation, added storage capacity, pipelines and even desalinization plants--there will be no easy choices.

The sole reservoir for the county, Loch Lomond in the mountains above Felton, holds only 8,600 acre-feet--enough to serve the city of Santa Cruz only for about nine months before running dry. But in recent years, thanks to growth and fading memories of drought, Santa Cruz County has been on the equivalent of a water spending spree.

The biggest storage areas we have are underground in aquifers capable of holding vast amounts of water. Because the county is rain rich but storage poor, groundwater resources, the only source of water for many parts of the county, have been depleted instead of being saved for, well, a rainy day. Getting more water into them is difficult. If Santa Cruz County could capture a fraction of the winter rains, either above ground or below, it could be water self-sufficient for decades instead of months.

Before the next drought hits, here's a crash course in where all that wet stuff comes from and who will be fighting over it when crunch time hits.

Hydro-reality #1: Californians are water-illiterate

Beyond saying "the tap," few county residents can answer the question of where their water comes from.

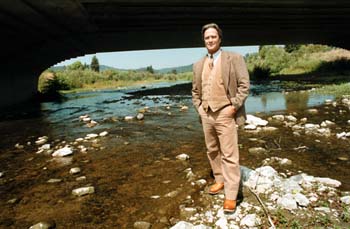

Drought Is a Loch: With well-water levels dropping, Loch Lomond is the county's only supply of above-ground water.

Back in the 1970s Bob Curry was teaching hydrology at UCSC. It was there he first encountered the myth of connectivity between Santa Cruz and the Sierra Nevada mountains. "I remember when I came to Santa Cruz and someone showed me a bottle of Crystal Springs water bottled in Santa Cruz, and there was this picture on the bottle of the High Sierra recharging the aquifer coming under the Central Valley and coming out the springs in Santa Cruz. And I thought, 'This is quaint. How can this kind of folk concept actually be printed on a label?'"

The drawing, he says, was indicative of California's profound illiteracy about water. "We are just living in the dark ages," Curry says.

Hydro-reality #2: Surface and ground water are connected, except in California law

While much of the hydrological game is taking place underground, political boundaries and water ownership don't reflect those realities. Even though Santa Cruz County is one of the few water self-sufficient counties in California, staying that way will depend on the political will of governments and water agencies to work together.

Water statistics from the City of Santa Cruz.

There are separate sets of laws in California for surface water and groundwater. The State Water Control Board governs stream allocations, while groundwater law is more complicated. Essentially you own the water rights to the aquifer beneath your land. But aquifers feed streams. According to Curry, the conflict between the two sets of laws and water reality results in a court system clogged with water-law cases.

"We have this official segregation where we say the hydrologic cycle doesn't exist," says Curry.

A case in point is the city of Santa Cruz. It gets 60 to 80 percent of its water from the San Lorenzo River watershed, but it has no authority over people upstream who pump water out of the aquifers that feed the river.

City water manager Bill Kocher says there was a time when the city got its full summer allotment at the San Lorenzo intake.

"That's not the case anymore," he says. "There have been many summers when the San Lorenzo River didn't flow enough for us to get our full allocation of 12.3 cubic feet per second."

The reason streams run at all in the summer when there's no rain is that they are flowing out of underground springs fed by the aquifers and by smaller tributaries. Depending on the size of the watershed, it may take four months or four years for rainfall to get into the creek. The water you're drinking now may have fallen on the Santa Cruz mountains in 1995. Individual wells along the river valley, and along Zayante and Bean creeks, combined with overpumping of the Santa Margarita aquifer in Scotts Valley, are lowering summer river flows, Kocher says.

To make up the shortfall, the city is drawing down Loch Lomond reservoir.

"I like to think of the river as a checking account and the reservoir as our savings," Kocher says. "You can't keep dipping into savings without feeling it down the line."

Hydro-reality #3: Aquifers store huge amounts of water, but we're pumping them dry

There are four or five sizable aquifers, or groundwater basins, in the county, along with many isolated pockets of groundwater each large enough to serve a few homes. They were formed over 50 million years ago through sedimentation and geological uplifting when the area of the county was covered by a series of shallow seas.

Earlier this summer, the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors was asked to declare a water emergency in the Pajaro Valley, where saltwater intrusion has been taking place in the Pajaro Basin aquifer since the 1950s. In certain sections of the Salinas and Pajaro Valleys, farmers have reported that wells are literally "pumping air."

Saltwater intrusion is also taking place in the Purisma aquifer, which feeds the Soquel Creek Water District, now scrambling for alternative sources and storage sites, and where an advisory commission earlier this summer called for building restrictions.

A similar saline intrusion is taking place on the North Coast, while underground water supplies in Santa Cruz, Scotts Valley, Lompico and the San Lorenzo Valley are also dwindling.

Aquifers are not big underground lakes. Think of rocks below the surface as a layer cake consisting of alternating layers of porous, spongy sandstone and hard, dense shale and clay. In the sandstone the small spaces between the sand grains create voids which hold water. In some instances as much as 30 to 40 percent of the sandstone can consist of these small water-filled voids. Because the spaces between the sand grains are very small, groundwater typically moves very slowly. It is this slow-moving underground body of water that is exploited in an aquifer.

Some of the water held in aquifers is "fossil water," which collected during the wetter climates and lower sea levels of the last Ice Age. We are essentially tapping a nonrenewable resource. The amount of water that can be taken safely out of an aquifer is limited to the percentage of water that flows in each year. This is called an aquifer's "safe yield."

Hydro-reality #4: Not all aquifers are created equal

Nearly every aquifer in Santa Cruz County is in a state of overdraft. In some cases, users are pumping 50 percent more than is being recharged. Aquifers that remain partially empty over time can become compacted or actually collapse, drastically reducing their capacity for future storage.

Jerry Weber is a professor of field geology at UCSC and has been a consulting hydrologist for 27 years. He says we are in deep trouble if overdraft continues.

"There's a limited amount of groundwater in the county, and we're mining it," Weber says. "It's a recipe for disaster."

This is Scotts Valley's big underground sponge. About 4,200 acre-feet per year are pumped, but the safe yield is under review.

The Santa Margarita groundwater basin consists of two aquifers: the Santa Margarita Sandstone aquifer and the Lompico Sandstone aquifer. Together they are the Scotts Valley Water District's only source of water and constitute half of the San Lorenzo Valley Water District's supply. A number of smaller customers also use the aquifer.

Since 1986, groundwater levels in the basin have dropped 150 feet in some places. In search of more water, Scotts Valley has drilled deeper into the Lompico Sandstone aquifer, which the 1999 County Water Resources and Management Report refers to as "the last known developable aquifer in the Santa Margarita Basin." It warns that the amounts being pumped from the Lompico aquifer "are not sustainable

This is the Soquel Creek Water District's main source of water. Some 5,480 acre-feet per year feet are pumped from the water district, which the water district says is about 600 acre-feet above its safe yield. Private wells take another 1,800 acre feet a year. According to the 1999 report, the safe yield is believed to be less than the rate of pumping. The communities served by this aquifer include Live Oak, Soquel, Capitola, Aptos, Seascape and LaSelva Beach.

The Pajaro Basin is made up of three aquifers, and there is some dispute over how much water is actually being pumped and what the safe yield is, as well as what the true extent of saltwater intrusion is.

The majority of Watsonville's water comes from groundwater. Hydrologists with the Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency (PVWMA) and the Soquel Creek water agency are studying the connectivity of their two aquifers using computer modeling.

"The implications of it being connected are that the boundaries of the two agencies are only geopolitical, not geological," says Bruce LeClergue, county water resources manager. "It's the same common basin. In the Purisima formation, conditions could be ripe for saltwater intrusion into mid-county over time."

The faulting and cracking of Ben Lomond mountain granite provides Bonny Doon residents and the city of Santa Cruz with the cleanest source of water in the county. Water for lower Bonny Doon and UCSC comes from a formation called "karst topography," a complex system of underground limestone featuring numerous caves and shallow pockets of water.

When RMC Lonestar's Bonny Doon limestone quarry planned to drill test wells on Smith Grade, nearby residents worried that their wells could be affected. When Santa Cruz wanted to pump brackish water from near the coast, residents up the hill were concerned about their wells going dry. The city is now investigating why their Lidell Spring water has become fouled with silt. The quarry, which is uphill from the spring, is a possible culprit.

Hydro-reality #5: Don't Pave Your Recharge Areas

Critical recharge areas are permeable soils or gravelly areas which allow water to percolate into the deep substrate. The longer the water seeps through the soil, the cleaner it is because the soil filters out impurities. When the soil is removed or paved over, water runs off faster and dirtier, causing flooding and sedimentation. It also bypasses the aquifers in its hurry to the sea.

Santa Cruz County has mapped its aquifers and the critical recharge areas which feed them and found that many are covered with concrete, which acts like a raincoat. Scotts Valley has blocked 33 percent of the Santa Margarita aquifer's recharge area. The San Lorenzo River watershed has lost 11 percent of its recharge capability to development. Some recharge areas, such as Bonny Doon, have minimum parcel size restrictions, protecting them from over-development.

Hydrologist John Ricker manages water quality for the county. He says the entire mountain of Ben Lomond is a critical recharge area for both the San Lorenzo River and coastside streams.

"The good news is that the density of building on most recharge areas is fairly low, except for Scotts Valley," Ricker says.

Bob Curry doesn't share his optimism.

"We've let the chickens out of the cage and we can never get them back in," Curry says. "We've let people build all over the hillsides without any regard for maintaining recharge capability in the countryside."

New county grading ordinances have attempted to deal with the problem of erosion and runoff, but Curry believes enforcement is too lax.

Hydro-reality #6: We all live downstream

Hydrologists are fond of saying if you live by a lake, you're drinking your own waste, and if you live by a stream, you're drinking someone else's.

Part of solving our water supply problems involves cleaning up the water we have. The Monterey National Marine Sanctuary has launched a program to encourage agribusiness owners to reduce farm runoff and conserve water. Farmers hope to head off more federal regulations by voluntarily altering their farming practices through the use of such things as drip watering systems and reusing nitrate-laden well water for irrigation.

With new satellite groundwater modeling tools, hydrologists will be able to help planners and governments decide how many straws can suck out of the same cup before it gets drained dry.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Santa Margarita Groundwater Basin

at the present gross pumpage of approximately 800 acre-feet per year."

Purisima Aquifer

Pajaro Basin Aquifers

North Coast: Numerous small private wells

In Santa Cruz County, beach closures at river mouths from "non-point source" pollution are on the rise. At river mouths in Soquel, Aptos and Santa Cruz, levels of 10 to 100 times beyond safe for bathing have been reported this summer. Bacteria levels in the streams are up 20 to 50 percent, and nitrate levels are five to seven times higher than they were five years ago. Twenty-five percent of the wells in the Pajaro Valley measured nitrate levels that exceed drinking water standards.

From the September 8-15, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.