![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Stroke Hold: Thomas Kinkade says his work isn't about making money; it's about bringing hope to the masses.

Cottage Industry

Thomas Kinkade, the Painter of Light™, aims his paintbrush at the collective craving for comfort

By Christina Waters

IN AN ART GALLERY in Carmel hangs a series of large oil paintings made by a young painter from Placerville. Dating from the early- to mid-1980s, they are confident, handsome mountain panoramas in the grand tradition of Albert Bierstadt, displaying painstaking craftsmanship and an unmistakable artistic gift.

The walls nearby, by contrast, are filled with paint-by-number-style landscapes depicting generic cottages, garish sunsets and crashing surf. These cloying greeting-card images, painted in the mid-'90s, are the work of the very same artist.

What happened in the intervening 10 years? To understand, we need to examine the transformation of a painter named Thomas Kinkade into a brand name: the Painter of Light™.

The Speed of Lite

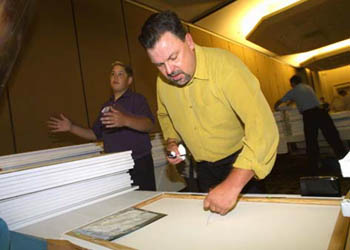

MOPPING HIS BROW with one hand and briskly scrawling his signature across the backs of canvases with the other, Thomas Kinkade works the eye of his current promotional storm like Martha Stewart on steroids.

"My work reflects a slower pace in the midst of a frenzied world," he rhapsodized in late June at the San Francisco Airport Marriott, a pit stop on his "Hometown" tour. "We do eight cities in a weekend." The irony of this revelation, in light of his claim to be an alternative to frenzy, appears to be lost on the trademarked illustrator, whose wife and brood of blonde daughters--identically dressed in Victorian frocks--accompany him everywhere.

Nor does he mention that this yearlong marathon of cross-country appearances is designed to boost sales, which are starting to flatten in response to the current economic downturn.

"My work is an icon of hope--an antidote to CNN," Kinkade beams, modeling metaphors in front of the video camera taping the interview. A big, beefy man in his mid-40s, Kinkade is a restless package of strong convictions. His face contains no softness.

"My work is about foundational life values, the peace that comes from nature when life was simpler." Leaving no cliché unturned in the sermon he has delivered many times to the media, Kinkade pauses only to adjust his belt and look upward as if expecting the right phrase to be handed down personally from the Almighty.

Kinkade says he deplores the "cult of the artistic ego"--yet more than 400 Thomas Kinkade Signature Galleries are in place worldwide (three in Santa Cruz county alone), splashing his name and boyish grin on every possible marketable item. High-tech disturbs Kinkade, who proudly disavows ownership of a television. This personal creed has not prevented him from working the airways each month pitching his inspirational collectibles on QVC, the home-shopping network.

"People would rather sit in the sun than surf the net," he theorizes. Nonetheless, a few clicks at the fully loaded thomaskinkade.com website will put you in the driver's seat of a "Classic Series" reproduction for around $300--framed. Populist to the core, Kinkade offers his work in a dizzying range of price points, from $10 coffee mugs and $20 screen savers, all the way to $1,500 signed canvas prints highlighted by the master himself. And Kinkade, who lives in the Santa Cruz Mountains, has recently lent his name to a new gated community development of $400,000 homes in Vallejo, where home and hearth look very much like, well, a safe, secure Kinkade reproduction.

Repro Man

PART ELMER GANTRY, part Donald Trump, Thomas Kinkade is an all-American success story. Born in the Sierra foothills, he was raised by a single mother after his father left the family. It's a story he bitterly loves to tell.

"I was an at-risk kid if anyone was. I knew the pain of a broken home, but I could draw. And that gave me self- esteem."

Self-esteem and a ticket out of his backwater hometown and on to study painting at UC-Berkeley. Today, Kinkade is a high-profile, born-again Christian who peppers his catalog blurbs and promotional homilies with bits of New Testament scripture.

Perhaps it was the need to give back to those less fortunate, powered by painful boyhood memories, that fueled Kinkade's charitable drive to give other kids tools for self-esteem. In addition to special auctions to support local charities, many targeting children, Kinkade has founded Art for Children, a nonprofit whose aim is to provide art materials and reinvigorate art training for youngsters in inner city areas.

In an upcoming visit with President Bush, whom he calls "W," Kinkade says he plans to suggest the formation of a "special council for the fine arts." Kinkade, who calls himself an idealist, believes that "artists have a contribution to make and that is to provide hope in the midst of oppression, a window on the world beyond poverty and despair."

"It's not about money," he contends. "It's about blessing others with my God-given abilities."

Philanthropy aside, Kinkade's personal response to the absent father and the broken home was to mythologize the American dream in artwork inspired partly by the Hudson River Luminist school of the 19th century, and partly by the thousands of animated backgrounds he painted while working on Fire and Ice, an animated film made by the Hollywood studio of Ralph Bakshi--a film that Kinkade freely describes as "terrible."

We may never know the source of the epiphany that led to his current mass-produced popularity. But we do know when it happened. In 1989, Kinkade's inspirational oil painting Yosemite Valley was selected for reproduction as a National Parks Collector's Print. Shortly thereafter, Kinkade forged an alliance with entrepreneur Ken Raasch and was reborn as Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light™. Suddenly galleries in Carmel bloomed with Kinkade's cottages, azalea gardens, lighthouses and atmospheric old-time village scenes. The Bradford Exchange and the Franklin Mint, distributors of mega-reproduced bric-a-brac, began cranking out his quaint imagery on "collectible" plates. And the rest is history.

The faith that had lapsed during Kinkade's college days returned. Kinkade, who holds forth on family values and God's blessings with the poise of a natural preacher, started adding the Christian fish symbol, as well as reference to John 3:16 beneath his signature. (It's easy to see why he didn't quote John 2:16, which admonishes the faithful: "Make not my Father's house an house of merchandise.")

If Kinkade's signature looks eerily familiar, it's because it mimics that of Norman Rockwell, a Kinkade hero, who in turn had copied the elegant initials of northern Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer when signing his Saturday Evening Post cover illustrations.

Whether Kinkade feels any conflict between the Christian values of marriage and family he espouses in each of the 40 inspirational books he has "authored" and the vast corporate structure devoted to hustling his work, he doesn't say. But the man feverishly signing and talking without pause about himself and his "message" did not appear to be having much fun.

"The world is full of darkness," he sighed. "There's great therapeutic value in art." With every dot of pale yellow paint in each and every cottage window, Kinkade takes back the night of his own broken childhood dreams.

Family Value: Kinkade's wife and daughters tag along during his yearlong promotional 'Hometown' tour, which sometimes covers eight cities in a weekend.

A Walk in the Woods

BY THE MID-'90s, Kinkade had fine-tuned his visual formula and unleashed a torrent of frilly, feminized imagery in which nature had not only been tamed, but neutered. It is a world without wildness, a diorama without Dad.

The populist appeal is epitomized by 1997's A New Day Dawning. Here we have the full Kinkadia--an artificially bright sunrise, crashing surf, soaring mountains, a cottage with smoke curling from each chimney, light blazing from every window, azaleas in full unrestraint, a come-hither pathway disappearing into a dappled woods. All is crowned by the Thatched Cottage, Kinkade's metaphor for the welcoming maternal womb to which we return through a rounded doorway.

"I think the appeal of his work lies in its simplicity," says Villanova psychiatrist Harvey Horowitz. "Its sentimentality resonates with people in the way a Hallmark card does." Horowitz cautions that this basic human need for simplicity is not to be dismissed but that while Kinkade's work seems to make people happy, it lacks weight and richness.

"Kinkade's world sees life as a walk in the woods where the vista is always inspiring," Horowitz says. "Yet that world really doesn't exist. What his work fails to recognize is the other side of life--the destructive, the aggressive, the evil. There are no dead animals in his woods."

Kinkade's imagery produces insulin overload in many viewers. To others, it offers an invitation to sanctuary and nostalgia. Picturesque and tidy, these are clearly the works of a man determined to annihilate confusion, whose own childhood lacked the very sense of home, joy and peace he so restlessly pursues in each and every painting.

Human beings are implied but seldom portrayed in Kinkade's Eden. This is its strength as well as its weakness. Lacking the observational power of Norman Rockwell, Kinkade work offers little psychological insight to disturb the peaceful emptiness. Kinkade claims his picturesque scenarios invite the viewer--any viewer--to step into the fantasy.

"When you paint people, you limit people," Kinkade explains, offering the example of a hypothetical Vietnamese-American family. "Why would they want to look at a picture of a dozen white people sitting around a Thanksgiving table?"

Point taken. People or no people, Kinkade's vision is very white indeed. His faux Cotswold cottages invoke the haven of blue-haired tourism that is forever England. One doubts whether many African-Americans would agree that his gauzy image of an Italianate stone walkway smothered by clouds of azaleas is their idea of a "Stairway to Paradise." Yet Kinkade the man, just like Kinkade the Painter of Light™, is sincerely convinced that it is their idea.

"In a culture of chaos, we need hope," he sermonizes. "On one side there's Jackson Pollock, and way over on the other side there's the Columbine shooting. And I know there's a connection between them. I don't know how, but I know it's there."

Gift of the MAGI

IT WAS A SAVVY marketing moment in 1990 when Kinkade and his business partner, Ken Raasch, founded Lighthouse Publishing Inc., now Media Arts Group Inc. (MAGI).

"We created a brand--a faith and family brand--around a painter," Raasch recalls with pride. "The Kinkade brand stands for faith as a foundation for life. He creates a world, and that world makes people feel a certain way. So we saw it as a great opportunity to create products around those worlds--collectible products, books, calendars, home décor items--furniture likely to be found in Thomas Kinkade's world."

Today, Kinkade galleries seem to clone themselves hourly in towns and malls all over the nation. Lining the walls of the green-carpeted galleries are images of serene gardens, stalwart little lighthouses, snowy Christmas landscapes and, most of all, cozy English-style cottages--cottages perched at the foot of mountains, at the edge of crashing ocean waves, tucked into sheltering forests, each one a gingerbread fantasy of soft thatched roofs and each sparkling with little dots of light.

Some may scoff at these tableaux of treacle, but the numbers are bracing. MAGI (of which Kinkade owns over 35 percent) soared on the wings of last decade's economic prosperity. Traded on the New York Stock Exchange, MAGI's net sales more than tripled in the past four years, to a stunning $140 million in fiscal 2000.

Kinkade's satisfied consumers self-medicate with his prints, screen savers, Bible tote bags, jigsaw puzzles, calendars, notebooks, mouse pads, beer steins, a trademarked line of Laz-E-Boy recliners and now a snug, protected housing development.

A Kinkade in every family room is the avowed mission of MAGI.

"Lots of artists have the opinion that publishing your work is selling out," Kinkade says. "They're hung up on the one-of-a-kind thing." Now he's really worked up. "I'm a messenger. You can't be one-of-a-kind when you're a messenger!"

The painter has chosen to "publish" his work in the form of inexpensive copies and to mass-market them in order to reinforce certain populist themes--to get that message across.

"People are frustrated--they just want some peace," Kinkade claims. Ten million people own something published by the Painter of Light™--and, as Kinkade likes to brag, "David Hockney can't say that!"

So many copies of Kinkade's work are floating around our national living room that the artist once found one of his prints at a local garage sale.

"And it was selling for only one dollar!" Kinkade wails in mock horror.

"He really is an accomplished painter," Raasch asserts. "He can out-Monet Monet, but he's chosen to make paintings that people can relate to." Raasch credits the ubiquitous Painter of Light™ trademark with producing crucial brand-name recognition and launching Kinkade into art publishing big time.

"The 'light' concept allowed us to develop consistency," Raasch explains. "There's always light in his work--yet that idea is broad enough that he would be free to do everything."

The concept is working. Four years ago, Kinkade stopped selling his originals, citing the desire to keep his collection intact for posterity as the primary reason. Focusing entirely on sales of state-of-the-art lithographic copies (available in multitiered editions priced from $300 to $15,000) allows MAGI to offer an endless stream of product.

Kinkade makes 12 paintings a year. The miracle of high technology does the rest. No longer CEO, Raasch still owns 25 percent of the corporate action and currently develops Kinkade lifestyle products.

"I can't talk about specifics, but we will definitely be broadening, with more focus for children--Disneyfying. And who better to do it than the No. 1 brand in American art?"

Canvasing the Crowds: The Thomas Kinkade brand already appears on books, calendars, mouse pads, notebooks, beer steins and furniture. Kinkade recently lent his name to a gated community of $400,000 homes in Vallejo.

Escape Artist

ART SHOULDN'T be about the artist," says Kinkade, "but about them, the people who need the message. It's the artist's responsibility to be accessible."

Not all artists agree. Painter John Moore, chair of the University of Pennsylvania's art department, who shows his work in a Manhattan gallery, articulates the difference between the work of fine artists and of what he calls "a degraded Currier & Ives."

"There are styles of art that have relevance in that they evolve out of a moment in history, out of cultural circumstances interpreted by individual genius," Moore says. "When somebody like Kinkade picks up a dead style, the soul of the work is already gone. It's no longer relevant."

In the way of perennial art students, Kinkade has mastered some styles of the Western painterly canon, Moore notes, but without any individual vision.

"He says he's an advocate of comfort--well everybody is," says Moore. "His work is just formulaic illusion."

Art historian Catherine Soussloff notes the romantic landscape tradition of the 19th century (from which Kinkade claims inspiration) "as the time and place for such sentimental expressions of nature as 'nation'--it was a time of westward expansion and empire building. Today this sort of work seems strangely contentless and inauthentic. It is nostalgic without being romantic, syrupy without being tastefully sweet, and it is about nature without being natural."

The idea that Kinkade revisits the same comforting territory each time he sits down to paint is "horrifying" to Moore. "Discovery is what making art--and being alive--is about."

And discovery is exactly what the creation of multiple generations of reproductions, each one a variation on the theme of home and hearth, is not about. The unique moment of artistic immediacy is blunted by multiple monotony, even though Kinkade attempts to compensate for that loss by employing a team of highlighters (80 at last count) who touch up thousands of his premium Kinkade copies.

Uniqueness is not what his collectors are after. They want to belong, to be part of a club of common values and tastes. Reassurance, not artistic vision, is what they're buying. And collectors like Capitola's Don Sanders are happy to join the club.

Sanders, a retired construction manager, began collecting Kinkadiana 10 years ago after visiting a gallery in the P of L's boyhood home of Placerville.

"We like the light part," Sanders explains. "The colors that he uses." Sanders also says that Kinkade's works went well with the Lilliput Lane cottages he and his wife collected. "They look like places I'd like to be and stay in."

Typical of many collectors, Sanders owns more Kinkades than his walls can hold. "We have 28 right now, and I've got all three of his End of a Perfect Day series; I even redid the living room just for his work."

What does Sanders see in Kinkade? "I like the fact that he's very family oriented--it's nice to see somebody that does so much for family values."

"We just enjoy his pictures, and wish we had more room for them."

A Kinkade consumer at the recent Marriott auction confessed that simply by gazing at one of his scenes she felt a sense of peacefulness that was otherwise missing in her life. Another collector commemorated her favorite Kinkade cottage by reproducing it in needlepoint. "It's brought so much happiness into our lives," she tells the Painter of Light™.

"That's what I mean," Kinkade booms triumphantly.

"My impression is that he's selling something spiritual and uplifting as part of the work itself, rather than allowing people to respond to its inspiration by themselves," says Cathy Kimball, director of San Jose's Institute for Contemporary Art and former curator of the San Jose Museum of Art. "The consumer is getting something mass-produced. I don't think there's anything educational or original in what he's doing--it's just eye candy."

But as we know, once upon a time Thomas Kinkade was a painter of no small talent. Those ambitious original oils from the 1980s, on view at his new Kinkade museum in Monterey, or his Carmel National Archives, are there to prove it. They are filled with technical expertise, even passion. An early painting, Block Island 1989, shows a rugged, richly observed rocky bluff and lighthouse before their trivialization into a marketing theme. Instead of dots of lite, the sky swirls with believable luminescence.

Once Thomas Kinkade became the Painter of Light™, he began to paint according to corporate strategy. It's possible that no one regrets this degradation of his skills more than Kinkade, who must live with the realization of what he forfeited to become a brand-name messenger. The gift of the MAGI was financial security, in exchange for the relinquishment of aesthetic discovery and the free play of imagination.

If Kinkade has regrets about the deal that has homogenized his skills, they are deeply embedded.

"Humans are essentially idealistic," says Thomas Kinkade, merchant artist, Painter of Light™. "They want to believe that somewhere, just around the bend, is paradise. I provide that paradise."

And it's available in three sizes, with your choice of frame.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Photograph by George Sakkestad

From the September 5-12, 2001 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.