Photos by George Sakkestad

In the Soup: Workers at the five Santa Cruz County New Leaf markets, such as these four at the store's 41st Avenue location, would be most directly affected by the opening of a new Whole Foods. Clockwise from left: Orion Davis, Jason Vergilio, Steven Padalino and Naomi Lieberman.

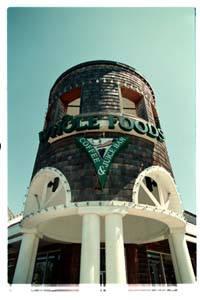

Unlike its Birkenstocked forebears, Whole Foods wants to sit at the top of the food chains

By Eric Bates

SHEILA PAYNE stands outside Whole Foods Market on a sweltering day. People hurry in and out of the store, eager to escape the heat, but Payne hasn't come to shop. She and three other activists are informing customers that the nation's largest chain of natural food groceries has refused to sign a pledge supporting better wages and working conditions for California strawberry pickers.

Many customers are stunned to learn that Whole Foods won't endorse the pledge for improved conditions, which has been signed by supermarket giants like Kroger and A&P, along with most of the nation's leading environmental and civil rights organizations. "I'm shocked," customer Sarah Wright says. "You would think they would be at the top of the list of stores signing the pledge."

Other shoppers share her surprise. "A store that prides itself on being concerned about organic food and other things that are healthy should also be concerned about the health of workers," says Pam Parkinson, loading a bag of groceries into her car. "It's important for human rights all over."

Faced with national pressure to sign the pledge, Whole Foods responded by holding a "National 5 Percent Day" to donate $125,000 of its sales to organizations providing health care to farmworkers. But at stores across the country, the company also distributed a brochure supporting the industry and attacking the United Farm Workers, which drafted the pledge. Top executives make no secret of their opposition to the UFW--and to all labor unions. "We're not signing a pledge that supports the union," Don Moffitt, a Whole Foods regional president, says. "If you say we don't support the farmworkers union because we don't support unions in general, I'd say that's true."

Whole Foods has taken a similar hard-line stance against environmentalists working to protect sea turtles. An estimated 150,000 endangered turtles drown in shrimp nets each year, according to the Earth Island Institute, a San Francisco-based organization that led the campaign for dolphin-safe tuna. But when the group approached Whole Foods about carrying shrimp caught in nets certified to protect sea turtles, chief executive officer John Mackey once again sided with industry and blasted the activists.

"We will not be coerced by Earth Island Institute or anyone else to support advocacy programs against our will," Mackey emailed the group. "Your attacks on Whole Foods Market are strategic mistakes."

Earth Island has responded by picketing Whole Foods stores in California and elsewhere. "I thought this would be right up their alley," says Todd Steiner, who directs the sea turtle program. "They claim to be really progressive, but their seafood counters are a big part of their profit margin. They've determined that this won't help their bottom line--and their bottom line is more important to them than doing the right thing for the environment."

Such an anti-activist attitude puts Whole Foods at odds with many of its customers, who believe that organizations like the UFW and Earth Island represent important forces for social justice and ecological well-being. People shop at Whole Foods not just because it offers organic produce and natural foods but also because it claims to run its business in a way that demonstrates a genuine concern for the community, the environment and the "whole planet," in the words of its motto.

In reality, Whole Foods has gone on a corporate feeding frenzy in recent years, swallowing rival retailers across the country and building what Time magazine calls "a billion-dollar juggernaut." Whole Foods now boasts 85 stores in 19 states, including its stores in San Francisco, Berkeley, Palo Alto, Los Gatos, Campbell, Cupertino and their newest store in Monterey.

The expansion is driven by a simple and lucrative business strategy: high prices and low wages. While Whole Foods makes millions selling organic and natural foods, employees complain that they are overworked and underpaid. Some start at less than $12,000 a year and cannot afford to shop in the stores where they work, despite employee discounts of 15 percent or more.

The chain's policies on wages and unions, its critics contend, contradict its stated commitment to empower its employees by giving them a voice in decision-making. "They tell you that you're part of a family and give you a chance to be heard," former Whole Foods baker Melissa Parsons says. "It all looks good on the surface, but eventually people discover that their opinion doesn't really count. The more involved you get in the company, the more the illusion is shattered."

Whole Foods is coming to Santa Cruz.

Love, Joy and Happiness

WHOLE FOODS PRIDES itself on being a different kind of grocery store. The company promotes organic farmers and educates consumers about agriculture and nutrition. It donates 5 percent of its after-tax profits to community organizations each year. It fills full-time positions only by a two-thirds vote of workers in the department that's hiring and fosters a diverse workforce that employees say is fun, friendly and accepting of a wide range of lifestyles. In January, Fortune magazine named Whole Foods one of "The 100 Best Companies to Work for in America."

"They treat their own workers exceedingly well," David Jernigan, a Whole Foods employee, says. "They don't have to do it--it's their philosophy."

Much of that philosophy stems directly from John Mackey, who opened a health food store called Safer Way in Austin, Texas, as a disheveled 25-year-old, six-time college dropout. A libertarian who combines New Age spiritualism with 1990s capitalism, Mackey sometimes sounds more like a cult leader than a CEO.

"When I peel away the onion of my personal consciousness down to its core in trying to understand what has driven me to create and grow this company," Mackey writes in the latest annual report, "I come to my desire to promote the general well-being of everyone on earth as well as the earth itself." One of his goals, he has said, "is to help create an organization which manifests love, joy and happiness."

From the beginning, Mackey derived much of his happiness from making money--lots of money--in an industry where that goal wasn't necessarily popular. "Profit is the lifeblood of every business," Mackey says. "It's like air."

Six years after opening his first store in 1979, he had expanded to three stores in Austin and one in Houston. In 1988, he bought Whole Food Co. in New Orleans and renamed his company Whole Foods Market, Inc. In 1992, Mackey bought Bread & Circus, a six-store New England company that was the third-largest chain in the region. Since then, every other natural foods company has become an acquisition target. Whole Foods now owns Fresh Fields, Mrs. Gooch's, Wellspring Grocery, Bread of Life and the Merchant of Vino chain. The Mackey empire also includes a coffee company, a vitamin company, eight bakeries and a seafood wharf.

Six years ago, Mackey believed the nation could handle only 200 natural foods supermarkets. With the industry soaring to $16 billion in sales this year, he has upped his estimate to 500, and he'd like most of those to have a Whole Foods sign out front. His company plans to open at least 18 stores over the next two years. A new store is planned for Santa Cruz soon, according to company officials (see sidebar).

Whole Foods certainly isn't hurting for money: Sales in the last quarter alone shot up 25 percent to $325 million. The chain has grown 900 percent in the 1990s, and some analysts predict it will continue to grow 25 percent annually for the next five years. At its annual meeting, shareholders burst into cheers when Mackey reported that Whole Foods stock had tripled in one year. "That's pretty good stock price performance," he noted, as the audience of 500 applauded and whistled.

With its big, inviting stores in affluent neighborhoods, Whole Foods has created a new standard for an industry once known for garbage bags full of granola and long-haired, Birkenstocked customers. The company has also blurred the line between conventional supermarkets and natural foods stores. Alongside natural and organic products can be found Clorox and Windex, Frito's and Honey Nut Cheerios, Star Kist Tuna and A1 Steak Sauce. Offering more products enables Whole Foods to cross over the counterculture line, generating healthier profits from less healthy food.

'Beyond Unions'?

'Beyond Unions'?

HOWEVER CONVENTIONAL his approach to growth, Mackey insists he has created an unconventional workplace. "Just as we are dedicated to providing excellent products and services to our customers, we are also dedicated to creating a positive, productive and enjoyable work environment," Mackey writes in the employee handbook. To promote participation, Whole Foods urges employees to think of themselves as "team members." Workers elect representatives to an advisory group, meet monthly to discuss concerns, and are invited to share their opinions with store managers and regional executives.

It's certainly not the kind of top-down management employed by most supermarket chains, and many employees say the process gives them a real voice in decision making. "I had a sense of dignity," former Whole Foods employee Christine Westfall says. "I felt my opinions were heard." Nearly half of Whole Foods employees nationwide completed a confidential morale survey last year, and 82 percent said they generally enjoy their work.

But when it comes to workers organizing themselves, Mackey sounds every bit the boss. He calls unions "parasites" that "feed on union dues" and compares them to "having herpes. It doesn't kill you, but it's unpleasant and inconvenient, and it stops a lot of people from becoming your lover."

In a 19-page treatise called "Beyond Unions," Mackey lays out a position on organized labor that views everyone--from Bill Gates to a single parent on welfare--as economic equals. Unions are unnecessary, Mackey explains, because "the foundation of a market economy is mutual voluntary exchange" between employees and employers. Translation: If workers don't like their jobs, they're free to go work someplace else.

Quoting the economist Milton Friedman, whose free-market theories formed the basis of Reaganomics, Mackey insists that "competition is the best protection for the largest number of workers that has yet been found or devised." Unions, he concludes, "are not part of the solution at Whole Foods Market. Rather they are part of the problem."

Whole Foods has repeatedly backed up its anti-union rhetoric with anti-union action. In 1988, the company refused to honor the United Farm Workers grape boycott and had union picketers at its Austin store arrested. In 1991, Whole Foods was forced to reinstate an employee in Berkeley after she filed a claim with the National Labor Relations Board saying the company had fired her in retaliation for her pro-union statements.

Three years ago in St. Paul, the company outbid family-owned R.C. Dicks supermarket for its lease and replaced the long-time employer's 50 unionized positions with Whole Foods' own lower paying, nonunion jobs. Last November, the company bought two Westward Ho stores in the Los Angeles area and promptly replaced 70 union workers with nonunion employees.

Whole Paychecks?

THE CONFLICT OVER strawberry workers comes at a time when some Whole Foods employees are expressing strong dissatisfaction with their own wages and working conditions. At the Whole Foods-owned Wellspring market in Chapel Hill, N.C., every member of the kitchen staff--the largest department in the store--recently signed a letter to the department's manager saying low wages and understaffing are undermining morale and fueling high turnover. Employees urge the company to improve wages to keep pace with growth, just as it upgrades equipment to meet increasing demand.

The company says it pays employees nationwide an average of $20,600 a year, but according to compensation guidelines in one region, annual wages for all full-time workers except meat cutters, bakers, buyers and team leaders range from $11,500 to $17,500. Wages are capped; once employees reach the ceiling, they never receive a raise. Whole Foods provides no cost-of-living increases, and overtime pay is almost unheard of. Those who work full-time receive basic health insurance or select other benefits from a menu of options, but any drop in hours means they must pay extra for coverage.

The wages and benefits at Whole Foods contrast sharply with those provided to grocery workers who belong to a union. Members of the United Food and Commercial Workers employed at Kroger grocery stores in the same region, for instance, receive hourly wages of more than $18,000 after several years on the job, plus annual raises to keep up with inflation and at least $1,800 in guaranteed bonuses. Those who work Sundays receive time and a half. Full health insurance, including dental and vision care, is free to full-time employees and their families, as well as to all part-timers and retirees.

At Whole Foods, the message for employees who want pay raises is simple: Work harder with fewer people. The concept is presented as a form of worker empowerment. "The teams have a huge amount of control over their own efficiency," says Portia McKnight, a Whole Foods store manager. "If teams run more efficiently, they can have fewer people. ..." She stops, reconsidering her words. "They can schedule fewer hours," she continues, "and be paid at a higher rate."

Workers at some stores have talked openly about joining a union. Labor organizing is a right protected under federal law, and Whole Foods says its employees are free to join a union if they choose. "If our team members ever felt that they needed to pay a third party to represent their interests with the leadership of Whole Foods, then we have fallen grossly short in upholding a core value of the company," President Peter Roy says.

At one Whole Foods store, though, workers say talk of organizing came to an abrupt halt when the company eliminated the job of an employee who raised concerns with top executives. "Everybody was totally freaked out," one worker says. "They knew if they talked about problems they were going to get treated the same way. It taught everyone a powerful lesson." Another employee who talked with co-workers about the benefits of organizing was approached by a manager. "The word's getting around you're talking about a union," the manager said. "You better knock it off. John Mackey hates unions."

The Bottom Line

AS WHOLE FOODS CONTINUES its quest to dominate the natural foods market, it's inevitable that workers will feel increasingly squeezed by the pace of growth and the demands of shareholders. The question is whether they will have the kind of voice the company has promised them in shaping their own workplace.

Mackey likes to call Whole Foods a "fun-loving family." But for some employees, the phrase evokes overtones of paternalism rather than cooperation, making it all too clear who is the father and who are the children. "They try to pretend they're this really lovey-dovey company, when in fact the bottom line is the dollar," says Lisa Longerich, who ran a Whole Foods bakery. "The bigger the company grows, the less it cares about the people who work for it."

It strikes many employees as hypocritical for Whole Foods to sell itself on its higher standards and then complain when it is held to those standards. If Whole Foods means what it says about empowering workers, they say, it cannot be satisfied to profit so richly from the low-wage labor of its employees--and it cannot listen only to those workers who agree with it. The true test of any participatory workplace is how it treats its most vocal critics.

"People who shop at Whole Foods should push the company to stick as much as possible to the original values of the natural foods movement," Christine Westfall says. "It's an issue of social responsibility. It's not enough to support the environment or cruelty-free products for animals. I think human rights should be at the top of that list."

[ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)