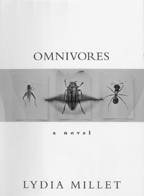

Bug Buffet

Lydia Millet hits home with surreal feminist tome

Reviewed by Michael Mechanic

Oppression eats childhood, eats hope. Children eat moths, eat worms. Cannibals eat meat, eat men. Omnivores eat everything, but women and children first. If any of this sounds strange, prepare to meet all of the above in Omnivores, Lydia Millet's first novel, a work as disturbing as it is riveting.

Millet, at 27 a babe in the literary woods, has delivered a tragicomic feminist tome--a surreal and twisted story of abuse and vengeance that, by not-entirely subtle metaphor, seconds as a scathing satire of American society and its shallowness, of the media and, in particular, of the male gender.

Our protagonist is Estée, named after the cosmetics queen by an invalid mother who saw it on a jar of cellulite cream. The mother, Betty--a pathetic creature obsessed with self-stimulation and anything to do with famous people or characters named Betty--appears to have been stricken with a faux paraplegia by virtue of her husband's ill marital graces.

We meet Bill Kraft on the opening page as he attempts to raise Estée under lock and key and imbue her with a bastardized scientific education (he is by choice, as she by lack of choice, an avid collector and taxonomes of insects). To Estée and reader alike, Bill becomes synonymous with oppression. He is one of the omnivores, an awful, corpulent tyrant under whose watchful tutelage Estée and the reader quietly suffer, unable to escape.

The mad mentor attempts to force his daughter to do cruel experiments on mammals, finally bringing in the ultimate research subject--a senile elderly woman. Our heroine, knowing her father is insane, refuses to accommodate his sick wishes with any research subject, save insectae.

Bill later skids over the brink in a new direction. He arms himself and secedes from the United States, hiring security guards as his own personal militia. Estée tries to attract the feds, but the bumbling FBI agents relate to her father far better than she ever did.

Estée escapes at 18 into the arms of another omnivore, Pete Magnus, a business acquaintance of her father. Her innocence provides comic relief as she studies humans in the outside world no differently than she once observed insects. Magnus, a real estate developer who represents shallow materialism, take advantage of Estée's naiveté in hopes of securing her trust fund and ultimately impregnates the teenager with the seed of his own undoing--for the combined blood of the omnivores creates a monster only Estée can control.

While the entire novel contains the satirical air of unreality, its resolution, beginning with the birth of young William, delves entirely into the realm of the surreal. The child--a tabloid headline-spewing cannibal--is Millet's deus ex machina, arriving to avenge Estée's oppression. Estée's supernatural son is a feminist fantasy fulfilled, and Millet's first work of fiction combines humor, violence and cultural criticism in such proportions as to make it thought-provoking reading.

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Omnivores

By Lydia Millet

Algonquin; 220 pages; $17.95

From the August 29-September 4, 1996 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books.gif)