![[MetroActive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

![[MetroActive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Heating Up the Nice

Fiddle Class Values: British Columbia's Carley Williams flexes her string-playing muscles amidst scores of other violinists at the Valley of the Moon fiddling camp in Boulder Creek.

Redwoods ignite with passionate rhythms as the Valley of the Moon Scottish Fiddling School prepares for its grand concert

By Traci Hukill

AS SUNLIGHT POURS THROUGH the redwood foliage high above, a hush falls over the crowd of musicians gathered in the outdoor chapel at Boulder Creek's Camp Campbell. The great Scottish fiddler Alasdair Fraser has begun to teach, and every fiddle player here is poised to listen like a pilgrim at an oracle. He's talking about rhythm.

"Rhythmic heat," he says in a butter-thick brogue, "the stuff that makes dancers dance until their feet are bloody. And it happens, and there's something about the magic of the fiddle that can bring that about."

To demonstrate, he raises his fiddle. "You can play this"--he marches out a well-behaved tune in perfect time--"or you can play this," and bursts into a rollicking, rhythmic version of the same song. Toes tap and heads nod. Comprehension dawns in a few faces.

Next it's the class's turn to try juicing up a sequence. Fraser tosses out a rhythm in his fiddle's throaty voice. Forty violins reflect the sequence back, sounding more like a chorus of angels than a band of rabble-rousing dance hall fiddlers. Their sound is sweet, strong, and elegant--but it's not fiddling, not yet. It's still too nice.

And nice is hard to shed. Many of the musicians here, like Catherine Mackintosh of London's Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, are classically trained violinists having to unlearn the instinct to blend and follow time, two rules the fiddle threw out long ago. The accomplished Mackintosh has made tentative steps toward rebelling against regimented perfection. "Even if you make a wrong move you think, 'That was a nice ornament!' " she chuckles.

"The germ of the difference is that in fiddle, you're using your own time source, and you're using older playing techniques," Fraser explains after class. "In classical you give up your clock. It's the great sacrifice. You become the servant of the conductor and the composer."

He follows this line of thought to its philosophical conclusion. "It's about the strength of the individual versus control of the masses." He laughs and turns a shade pinker, aware of how weighty this discussion just became. "I can't go there too often because people get uptight about it."

In truth, Alasdair Fraser could say anything he wanted to around here and be forgiven and probably thanked for it. The award-winning musician grew up in Scotland in a musical family and went on to establish an impressive discography that includes "Dawn Dance," for which he won top Celtic Independent Album for 1995. He now produces albums out of his home in the Sierra foothills.

But the reason Fraser is so loved in these parts is that 14 years ago he started a Scottish fiddling camp in Sonoma County's Valley of the Moon, a location the camp outgrew in a scant two years. Fraser kept the name and eventually settled on Camp Campbell to host the annual convocation of musicians, dancers and singers.

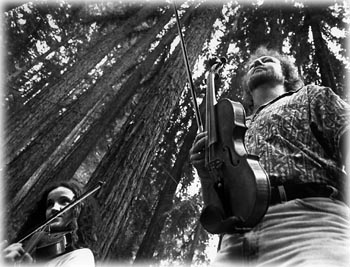

Trunks of the Trade: Acclaimed Scottish fiddler Alasdair Fraser, founder of the Valley of the Moon fiddling camp, now plays host at an annual convocation of musicians, singers and dancers at Boulder Creek's Camp Campbell.

Amateur Ours

NO EXPERIENCE IS necessary to attend this school, so its ranks swell with novices. This year almost 200 people of all experience levels paid over $400 each to attend a week's worth of workshops with Fraser, six-time Irish fiddling champion Martin Hayes, Appalachian fiddler Bruce Molsky and a handful of other artists. The camp culminates in a grand concert each year (this year it's at Cabrillo).

The school is so popular that enrollment is partially determined by lottery. In spite of the cost and the time commitment, everyone agrees it's well worth it. Fiddlers, cellists, guitarists, pipe players, singers, drummers and dancers have trailed in from Scotland, Australia, all over the eastern United States and, of course, California to attend.

"There's an element that can't be captured by playing a record or reading the notes," says Greg Berger, owner of Joplin & Sweeney Music Co. in Los Gatos and himself a teacher of Scottish fiddling to a score of Santa Clara Valley students. "There's a sense among the campers that here's really an opportunity to mine these gems and learn from these people."

The instruction is priceless, but what happens outside the workshops is what keeps people coming back. Every hollow and glen in this spacious, canopied property cradles musicians. A woman practices her harp alone at a picnic table. Listeners creep up one by one to hear Scottish singer Norman Kennedy and a friend exchange stories and songs. Master guitar teacher Dennis Cahill and fiddle recording artist Laura Risk jam together in a redwood grove while a pipe player embellishes the tune.

In a shallow hollow, 10-year-old Rosie Newton of New York, here for the third year, works on a tune on her fiddle until she gets it. "I wish I could be here all the time," she says, her blue eyes twinkling. "We also square dance at night."

Dance is an integral part of the school. Many of the musicians are also folk dancers, and it's typical to see people practicing their steps while they listen to the musicians. As Cape Breton pianist Barbara McDonald Magone demonstrates the pure, swinging style for which her North Atlantic home is known, a couple of women in the back of the room nod in time and surreptitiously shuffle their feet in the Cape Breton step dance.

Dance instructor Eileen Carson is on her way, coffee cup in hand, to spend some time alone before her class begins. A straight shooter with dark silvering hair and a steady gaze, Carson directs Footworks, a Maryland-based ensemble that performs ethnic and roots dance forms like Appalachian clogging and flatfooting. On paper her job here is to coach dancers for Friday's performance, but she downplays routines and practice, focusing instead on coaxing individual style from her novice students.

"I'm trying to emphasize the person coming out, so it's not to be critiqued. In some ways it doesn't even belong on stage," she says. "Some people view that as namby-pamby-how-sweet, but I'm process-oriented, not product-oriented.

"When you're an artist, you're what? Vulnerable. Especially if you're a beginner and especially if it's your body. People see that, and they respect it. And people get off on it."

Experimental Enlightenment

CARSON WILL TEACH a routine eventually, but today's class is about dropping inhibitions. In a lofty, well-lit room, some two dozen students are experimenting with body movement while Fraser plays an achingly sweet "Oh, What a Beautiful Morning." The hall is silent except for the plaintive fiddle and the swisp of bare feet across the floor.

People raise their arms and twirl like kids playing ballerina or dance as if they were waltzing with ghosts. "Be experimental," Carson urges. "Don't look at others for what you should do."

Across camp, Abby Newton is teaching a dozen cellists next door to Barbara Magone's piano class, making a happy cacophony of the porch between the two halls. Outside, at the base of a sloping hill, Chris Caswell leads a rhythm class for students of the bodhran, or Irish drum, and up a short footpath, traditional singer Norman Kennedy starts his workshop.

Seated before a small group, the white-maned singer closes his eyes, tilts back his head and breaks into a haunting, intricate melody sung in lilting dialect. Those who know the chorus join in softly. Most just listen, soothed by Kennedy's brogue and the tune's hopeful sorrow.

And between the halls and groves where instruction takes place, a contemplative sense of community joins player, dancer and observer alike. This outdoor conservatory, where airs and melodies float on every breeze, sets the scene for another chapter of fiddling's grassroots musical revolution.

This is the music of the common people, and it has endured for centuries despite legendary crackdowns like the one that once had every fiddle on the Isle of Skye burned.

That's not to say these musicians are burdened or somber. Those moods are best reserved for the mahogany-paneled conservatory, not the fresh-air school of rhythmic heat and tired dancers' feet.

These are people like fiddler Howard Booster and cellist Susan Stewart, who laugh between songs from their practice room inside an enormous hollowed-out redwood trunk--folks with open faces and ready smiles who play music that make the dancing and living worth doing.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Robert Scheer

Robert Scheer

Valley of the Moon Scottish Fiddlers: Over 170 musicians, singers and dancers perform a grand concert of airs, jigs and Scottish and Appalachian dance tunes on Friday (8pm) at the Cabrillo College Theater, 6900 Soquel Ave., Soquel. Tickets cost $12/$10, less for kids and seniors. For more info, call 479-6331.

From the Aug. 27-Sept. 3, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.