![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Future Shock

Otherworld: Raised in the Bay Area and splitting his time between Palo Alto and London, author Tad Williams imagines an online future not dominated by America.

For sci-fi author Tad Williams, mid-21st-century cyberspace looks a lot like today

By Rob Pratt

"HOW OLD ARE YOU?" bestselling author Tad Williams asks me. "I bet you're about 10 years younger than I am."

I had called Williams at his Palo Alto home to talk about Otherland, his cyberpunk saga, a tetralogy (one Amazon.com wag dubbed it a "megaology") following an eclectic, mid-21st-century band of adventurers through a virtual world as engaging--and dangerous--as "Real Life." I asked about his vision of the future and whether he thinks the sci-fi future in general has changed in the past decade from one of postapocalyptic Road Warrior scenarios to something a little more optimistic.

It was a funny response, asking how old I am. But he guessed my age--10 years younger than his 42--exactly right.

"I was talking with my brother at a family gathering, and he's as old as you are, 10 years younger than me, and there were some of his friends with him, all of them about the same age," Williams explains. "We were talking about the '80s, and he and all of his friends remember growing up then with this constant fear of nuclear war--like every day.

"That's one reaction I never had to the '80s," Williams continues, already talking fast and building momentum. "People my age remembered the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Vietnam War, and by the time the '80s came around, we just figured that Reagan and those Bozos couldn't hurt us. So Otherland is a bit of a litmus test. Some people say what a pessimistic future it shows, and others say what an optimistic future.

"Overall, my feeling is that human beings have muddled along for however many thousands of years, and they'll keep going for however many thousands more," he adds. "People always talk about how the generation behind them is going to hell in a handbasket--but people have been saying that since Plato's day."

When Williams stops at the Capitola Book Cafe Tuesday on a tour supporting his latest novel, Otherland, Volume III: Mountain of Black Glass (Daw Books), he will arrive with more questions than answers about the future. They're big questions about the role of technology in the world--that much is obvious by the sheer size of the Otherland books, each running in the neighborhood of 700 pages. Despite the epic proportions of the story (perhaps a literary indication of Williams' mile-a-minute thought process), Otherland has sparked a phenomenon, drawing even fans who don't normally read science fiction with a mix of futurism, fantasy and social criticism.

The saga opens with an unlikely pair of cyberheroes: Renie Sulaweyo, a black South African woman specializing in network studies at a university, and her savvy Bushman pupil, !Xabbu (which Williams indicates is roughly pronounced as "KAY-bu"), whom she introduces to the online world. When Renie's younger brother, a teenaged "netboy" named Stephen, ends up in a coma after hacking into an exclusive online club named Mister J's, Renie and !Xabbu stumble into Otherland, a secret online realm constructed by a cadre of the world's most powerful capitalist mavericks. Trapped--unable to sign off and return to Real Life--they join a band of other unlikely heroes caught in Otherworld and travel through simulations of insect kingdoms, cartoon worlds and an Osiris-dominated ancient Egypt to track down the secrets of Otherland's ruling clique, the Grail Brotherhood.

Like a jumble of larger-than-life Nintendo Playstation backdrops, e-commerce malls and sleazy chat rooms, Williams' idea of a mid-21st-century Internet casts a long shadow backward to the inequalities and monolithic culture of the contemporary online world. It's a place where class divisions are stark--only the wealthy can afford attractive, full-featured avatars on the 'net, and everybody has to pay by the second to walk the better districts of the online megalopolis. And everything seems vaguely American.

"I grew up in the dogmatic days when white, military males were always expected to put the world right," Williams says, adding that those days haven't necessarily ended. (He was "deeply and vastly irritated" at exactly that attitude in the movie Independence Day.) "The entire world standing back helpless while the U.S. saves the world is an idea of ridiculous arrogance. From living in the U.K. and Europe, I've learned that the shining pre-eminence of America is a pretty blinkered view. I've deliberately picked several characters who didn't have that. The culture of the world still looks American--that's where it comes from. But America doesn't dominate it once it gets out into the world, and Renie, a black South African woman, is about as far away from that as you can get."

!Xabbu, by contrast, Williams explains, reveals not only how far technology might advance in 50 years but also how little the world has changed since the entire scope of human experience was limited to hunter-gatherer societies.

"There's a dichotomy--perhaps a false dichotomy--that says there's a divide between the human ways of doing things and the technological ways of doing things," he says. "But that's a fallacious idea--it's not a dichotomy. More and more we're moving toward a universe that's somehow connected to an earlier idea of human experience.

"Just look at the notion of the observer in quantum physics," he continues. "What happens is totally dependent on your point of view."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

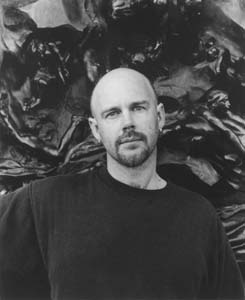

© Patti Perret 1996

© Patti Perret 1996

Tad Williams gives a free talk Tuesday (Aug. 31) at the Capitola Book Cafe, 1475 41st Ave., beginning at 7:30pm.

From the August 25-September 1, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.