![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Toast of the Coast

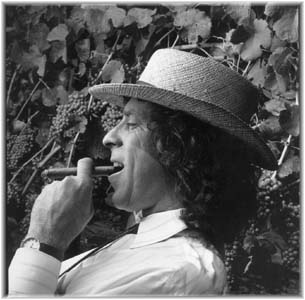

Been There, Doon That: Bonny Doon Vineyard's Randall Grahm and other California vintners lead a heady trend in overturning old wine-drinking preferences by introducing the public to wines like syrah, riesling and grenache.

As more and more vintners chart new ground, the good word is spreading about Central California wines

By Christopher Weir

'TWO TYPES OF PEOPLE drink pink wine," says Randall Grahm, owner of Bonny Doon Vineyard. "The terminally hip and the terminally un-hip." As the good-natured purveyor of the eminently pink Vin Gris de Cigare and other esoteric ambrosias, Grahm is the last person to pander to wine elitism. But his point is well made: Many of the most progressive California wines are those often confused with the dregs of the oenological netherworld.

They are the maligned, the misunderstood and the unknown. They are the ethereal dessert wines, the dry rosés and dry rieslings, the grenaches and the teroldegos.

And now, more than ever, they're coming to a wine list near you, thanks in no small part to the iconoclastic individualism of Central Coast vintners and the ever-expanding tastes of West Coast consumers.

"There's a huge revolution going on here, in Australia, all over the world," says Ridge Watson, winemaker at Carmel Valley's Joullian Vineyards.

"It's a real dynamic, fertile time for ideas and change," adds Jim Moore, program manager for Robert Mondavi Winery's Bocci and La Famiglia labels. "And the Central Coast helped catalyze it all."

Until recently, the California wine marketplace was literally hypnotized by varietals native to two French regions: Bordeaux and Burgundy. In other words, cabernet sauvignon, merlot, sauvignon blanc, chardonnay and pinot noir. Meanwhile, all but a few premium vintners and consumers remained unmoved by the notion that Germany, Italy, Spain and Southern France had forged their own stellar wine traditions via entirely different varietals and styles. Worse yet, the American wines that were supposedly evocative of these forgotten regions--white grenache, jug "chianti," one-dimensional sweet wines and cheap, mongrel red blends--had become the pariahs of an increasingly sophisticated yet provincial consumer base.

Undeterred, however, were a few wineries--including the Central Coast's Bonny Doon, Qupé and Claiborne & Churchill--that were willing to blaze trails and confront the marketplace with such things as syrah, roussanne and dry riesling. And while they may have had to put in serious retail and marketing overtime, their tradition of success is now paying exciting consumer dividends.

"They're the ones willing to take the risk," says Doug McCall, Central Coast regional manager for Wine Warehouse, a major wholesaler. "And you know that the big boys are in the wings, watching the entire time to see what works."

Indeed, that's exactly what's happening as more and more vintners, including such heavyweights as Mondavi and Kendall-Jackson, are emboldened to expand their portfolios into uncharted territories, such as those of Tocai Friulano and Tempranillo. And many wine enthusiasts are responding with broadening demand.

"It's just a normal progression in the sophistication of our society," says Doug Meador, owner of Monterey County's Ventana Vineyards and longtime booster of riesling, gewürztraminer and syrah. "We're experimenting with all different kinds of spices and food flavors from around the world, and learning that there are these different flavors of wine that will go with different food combinations."

Nevertheless, just because there are more choices out there doesn't mean that sangiovese is going to knock merlot off its hallowed perch anytime soon. While more and more American wine consumers may be open to new flavors and experiences, the majority still rarely hover outside familiar territory. It's a dynamic rooted to a large degree in decades of misguided elitism brokered by the broader wine industry.

For example, Grahm says, "People are phobic of pink wine, and they fear it's a great social faux pas to order it in a restaurant, even those who should know better. So it takes a tremendous amount of courage."

In other words, so what if a particular rosé or riesling is drier than the average $10 chardonnay? Or if syrah is often more supple and alluring than the average merlot? As long as consumers fear ordering, purchasing or mispronouncing the "wrong" wine, there is little incentive for exploration.

Mining Taste Patterns

SO FAR, THE SO-CALLED "new" varietals that hold the most promise for a mainstream market presence are syrah and sangiovese, which hearken, respectively, to the benchmarks of France's Rhône Valley and Italy's Chianti. "When you pour a glass of syrah for someone," Meador says, "they may not know what it is, they may not know much about it, but the predominant and immediate reaction is, 'Oh, I like that.' When I start seeing that over and over and over again, that tells me that's a flavor profile that matches the taste patterns of the American wine-drinking public."

Nevertheless, Watson maintains that most, if not all, of the newcomers will, for a long time, remain in the "faddish or high-end niche market." He adds, "A good example is gewürztraminer. There's a wine that goes with about 80 percent of anything you want to put with it. I predicted in 1970 that the next hot deal was gewürztraminer, that it was going to knock out riesling. Well, chardonnay knocked them all out, and you don't hear from any of them any more. You can't find two rieslings on a wine list."

For now, the consumer compelled to embark on an alternative varietal adventure should proceed with caution. Simply put, it's easy to confuse the unproven with the exotic, especially when navigating high-priced territory.

"You're paying for a lot of experimentation," McCall says, "You're paying the limited yields, the limited distribution, the cost of the marketing and sales. Not everyone is clamoring for these wines. They really have to be sold, and that costs more."

So how to find progressive wines that will deliver the goods at a justifiable price? The key is to become familiar with the different wines and their producers while consulting trusted retailers or restaurateurs. (Wine magazines can also provide purchasing direction, but beware the urge to obsess over their highly subjective and sometimes dead-wrong "scores.")

"You probably want to tie in with some of the local independent retailers," McCall says. "They have the best selections of allocated wines. Also, they regularly taste the wines, and they understand them."

Then, instead of jumping into $30 or $40 bottles, it's perhaps better to purchase two $15 or $20 recommended bottles of the same varietal or style. Chances are the quality will be comparable, which means double the experience, as well as double the pleasure.

"Find wines in a comfortable price range," McCall recommends. "Taste some together so you have a reference point, and go from there. Remember, price doesn't always equate to quality."

Tracing wines back to their European roots is also a good idea: The dry rosés of the Mediterranean, the spectrum of Rhône Valley offerings, the sophisticated dessert wines of Germany, the chiantis and riojas, as well as other archetypes that illuminate synergies with their California counterparts.

And, finally, it couldn't hurt to indulge in the adventurous enthusiasm shared by California's pioneering winemakers. "There's no formula or recipe to precede this," Moore says. "The next decade is going to be really exciting. I'm having the time of my life."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Jack McDonald

From the August 21-27, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.