![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Suits to

Slaughter

Fat, greedy and full of itself--what's not to like about the music industry? Bill Flanagan tells all about the waning days of A&R in new novel

By Gina Arnold

IN RECENT WEEKS, the dialogue about the digital downloading revolution has become positively deafening. Everyone has an opinion on Napster, MP3 and the like, from Deadheads to United States senators, but few people want to address an issue that will have equally long-term consequences for the music business: namely, that there are fewer and fewer new artists making it up the ranks.

Although record sales have actually increased by 8 percent for the year 2000, the charts are overridden with boy bands, teeny-bopper sensations and aggro-hate-rock groups--acts that have almost no long-term earning potential. Eminem and Britney Spears enjoy a celebrity life span of a few years at most, while bands with less trendy intentions are having a very difficult time getting heard or signed.

Indeed, just as file-sharing programs like Napster and Gnutella burgeon as a way for consumers to hear old music for free, the creative end of the music business--the side known in the industry as A&R, for "artist and repertoire"--languishes in a huge slump.

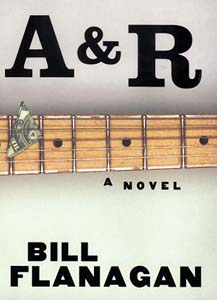

This is one reason that the new novel A&R, by Bill Flanagan, is so fascinating. The other is simply that it is a really good read; a cranky, poignant and fun-filled snapshot of the pre-Napster world of the music business in all its sleazy glory.

Had I read A&R 10 years ago--in 1990, when I first heard Nirvana, for example--I'd have been outraged at the industry it portrays. Now, I practically feel nostalgic, because Flanagan writes about a world gone by. And as such, the novel explains a great deal about the predicament that industry finds itself in.

Be Careful What You Wish For

THE BOOK BEGINS with three record company execs, including WorldWide Records president Wild Bill DeGaul, his right-hand man, J.B. Booth, and newly minted A&R guy Jim Cantone (the novel's Candide), taking a goofy trip on a private jet to Brazil "to check out our Latin markets," as the big guys tell Cantone with many nudges and winks.

The plot then careens merrily along through numerous trips to a Caribbean island--not to mention forays to Europe and London--as Cantone, a likable but slightly dumb college-radio DJ turned A&R guy, finds himself being paid a quarter of a million dollars to baby-sit bands and ends up turning a blind eye to various and sundry internecine wars and sleazy business practices.

In addition to various record company machinations, the book glides by many a stock character in the rock world, like the crack-fiend diva who is coddled through her addiction; the conniving new country star who sleeps with the president of the company; and the struggling alt-rock band that keeps pulling "integrity" moves on the company in order to counteract its "corporateness" (thus, inevitably, sabotaging the band's career).

The situations are fictional, of course--although it is hard to legally suppress names like Whitney, Mariah and No Doubt from swirling about in one's head while reading A&R. Meanwhile, everyone involved is continually getting wined and dined and wheedled and bribed--all on expense accounts, of course--with the expenses charged back to the bands' royalties.

Flanagan introduces us to various hilarious and pathetic aspects of the music business: negotiations with has-beens, recording sessions that go wrong, weird political fundraisers in the Hamptons, back-room schemes to fiddle with stock prices and take over the label, and so on. He even throws in a complex subplot involving a small Caribbean island that gets flooded with free cocaine, clearly a zany metaphor for the old adage "Be careful what you wish for; it might come true."

That is always great advice, both in the rock world and out of it. And yet, throughout much of the story, despite evidence to the contrary, Cantone continues to believe in the regenerative nature of rock & roll, and it is this belief that makes the book both bearable ... and poignant.

Smells Like Teen Disillusionment

IN THE END, A&R is a novel about disillusionment with both the record business and adult life in general--and that's a subject we all can relate to. That sense of weltschmertz for lost innocence is best addressed in a wonderful sequence in which Cantone drives up to his parents' modest Maine house in a Mercedes, and his sister cracks, "A Benz! I love it! I guess we've gotten over the trauma of Kurt Cobain's suicide then?"

Cantone is hurt by what he sees as her cynicism, but the scene really sums up much that is wrong with the record business. "His family," Flanagan writes, "made Jim feel like the world he was in was the most trivial and superficial place in the universe."

That's because it is, of course. And the fictional Jim Cantone's total inability to see the truth of that perception pinpoints the reason the record industry has slipped up on digital downloading and why the force of opinion in favor of Napster has taken them by surprise. It's the same lack of insight that Metallica's Lars Ulrich keeps exhibiting when he says things like "it's sickening to see our music treated as a commodity, instead of as the art it is," or calls Metallica's most devoted fans "common looters."

In fact, legally, Metallica has a great case against Napster. But it's hard to blame fans who've bought and rebought every Metallica--or Beatles or Stones or Bruce Springsteen--record in three formats, who will spend more than $100 to watch them play live and who continually see their heroes ensconced in mansions on hills for not feeling guilty when they do something as simple as download a song to their hard drive for their own personal listening pleasure.

Meanwhile, to complicate matters, the five major record labels currently suing Napster have themselves just been sued by 24 states and two U.S. commonwealths. They are being charged with having conspired to artificially inflate and fix CD prices, starting in the early '90s. The suit, if lost, could cost the industry as much as $480 million in damages.

Similarly, A&R showcases how the industry has failed to understand, partly through ignorance and partly through greed, the public's needs and wants, willfully mistaking its deep love of music for rank stupidity. The result is a summing up of sorts. Thus, near the end of the book, Booth tells Cantone the collective philosophy of the music honchos of the 20th century:

Jim, nobody knows what's going to happen with the record business in the next ten years. I don't know if people will be punching up music online or over the telephone or through the radiator. I don't know how much longer we few old shops are going to get all the money just because we own all the trucks and pressing plants. But I can tell you this. We've had a great run. A hundred years of keeping ninety-five percent of the money and all the rights! Who'd have believed it? How can we complain? If the roof falls in tomorrow, if the means of production go into the hands of the artists, or Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos, or whoever the hell it's going to be, just make sure you've got your ass covered. Get yourself an artist who'll make you rich before the bottom falls out. I don't care if it's a Britney or a Ricky or a Sporty or the return of the rhumba. But find something that won't take ten years to pay back your investment, because honest injun, in ten years I don't know if you, me or the industry will still be here.

Cutting the Fat

THAT PARAGRAPH is probably even more prophetic today than when it was written sometime last year. But then, author Bill Flanagan has long been in a position to know which way the wind is blowing. As a former rock critic and editor of Musician who currently heads programming at VH1, he has been observing the machinations firsthand for quite some time.

Even so, his prescience on this one is a little bit uncanny. Flanagan finished A&R in June of 1999--the same month Napster.com was being made into a company--and the result has turned what was originally just an ordinary novel into a fin de siècle statement.

"I didn't anticipate that when I started it," he says now, "but it did wind up being an elegiac kind of thing, a sort of Edith Wharton, end-of-the-century, 'there it goes' moment-in-time thing."

Does the book reflect how people in the music business are thinking now? "Oh yeah," he says. "More than ever. The anxieties that propel the leading characters--the idea they have to make a bunch of money fast or it's all going to go away, what with mergers and being sucked up by the Internet, is very much present.

"Working in the music business today," he adds, "is a lot like working in the horse-and-carriage industry in 1905. All your life, you've thought people will always go places by horse and you'll always be in business. And then all of a sudden, there's this hint that maybe they won't."

The music industry's greatest fear is that the digitalization of music distribution will send down its costs--thus cutting the fat off the profit per CD. One might think, Well, so the big guys won't be able to fly to Brazil so much anymore. But, in fact, the effects will be more far-reaching than that.

For one thing, as Flanagan says, "Someone will always be flying to Brazil. Only now, it'll be whoever ends up as toll taker on the Internet music highway."

For another, it takes a lot of money to make a superstar like Madonna. And as Hilary Rosen, head of the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America), pointed out recently, 15 percent of the artists in the music industry pay for 100 percent of the music produced by the industry. The Michael Jacksons of the world--even with their big-budget videos and lifestyles, and concomitant huge sales of CDs--pay for the Wilcos, the Tom Waits and so on.

That's why the place where any loss of profit will be felt most is in A&R. Flanagan thinks that, in the next few years, the A&R departments of the world "are going to mean less and less. I think Napster is an interim technology, like streetcars or the 8-track tape, that's going to go away, but eventually, digital downloading is going to liberate musicians entirely, because listeners at home won't be prejudiced by whether music they hear is made by million-dollar labels or in a bedroom. They'll just decide what they like."

With that prospect ahead, it's no wonder the music business is reacting with fear and trepidation. Last week, EMI inaugurated a digital downloading system of its own--where consumers can, if they so desire, download MP3 files of CDs for the exact same price they pay in the store (only with more restrictions on their use). Emusic.com has instituted a subscription service ($9.99 a month to download anything on their files), and other record companies will be following suit with differing methods of downloading and payment schemes. With Napster (and programs like it) still in existence, none of the schemes are particularly appealing. But that doesn't mean digital downloading isn't a working proposition for the industry--eventually.

"I think, in the long run, it's a real positive thing," Flanagan says, "but in the short run, it's a pain in the neck. I feel sorry for artists who are stuck contractually to the old way while this is being worked out. But 10 years from now, it won't be an issue. Royalties will be paid out, the intermediaries will be pushed aside and the artist will be king."

Flanagan is wholly in favor of that development. Nevertheless, he says, there's an inevitable sense of sadness when he surveys the history of rock. Despite the greed, the corruption, the sex and drugs and so on, the '60s, '70s, '80s and '90s were a pretty amazing time, storywise, and it's hard to look back in anger.

"You know, when I started the book," Flanagan says, "I already knew who all my characters were going to be, and I imagined it would be a lot more scathing--more like Money by Martin Amis. But when I finished writing it, I ended up feeling a lot more affectionate toward them all than I ever would have thought. You know, I spend all day long fighting and cursing and tearing my hair out at a lot of people just like this. But I don't know--when I separated them out and made characters of them, I really ended up getting a kick out of them.

"I guess I figured out why they were behaving how they did, and I realized they all had good hearts deep down. In the end, it was kind of like high school. It drove you crazy to be there, but there's a fondness you feel looking back."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

The Past Recaptured: Bill Flanagan captures the waning glory days of record-industry excess and offers some clues to the future of the music business in his new novel, 'A&R.'

National Fret: Novelist Bill Flanagan finished 'A&R' the same month that Napster.com became a company and challenged the old model of the music industry.

National Fret: Novelist Bill Flanagan finished 'A&R' the same month that Napster.com became a company and challenged the old model of the music industry.

A&R: A Novel

By Bill Flanagan

Random House; 368 pages; $22.95 cloth

From the August 16-23, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.