![[MetroActive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

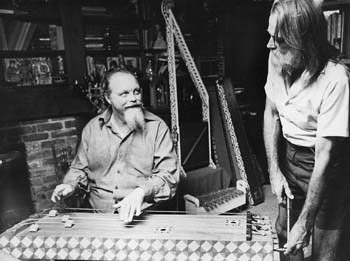

Sound Mechanic: With longtime partner, composer Lou Harrison (left), Bill Colvig created many unique musical instruments, making an indelible contribution to classical music. A Sound Life Longtime Lou Harrison partner Bill Colvig crafted an artful contribution to music that resonates with ingenuity By Phil Collins WILLIAM COLVIG'S quiet exit from this planet on March 1 left hearts saddened the world round. Composer Lou Harrison's lifetime partner, musical collaborator and sometime secretary had come to renown in his own right by age 82. As the co-designer and primary builder of three gamelans (Indonesian percussion orchestras) and innumerable new instruments of his and Harrison's invention, Colvig is now recognized as a major--albeit behind-the-scenes--contributor to the soundscape of American music. Those who knew Bill personally hold his character in equally high regard. Bill was quietly remarkable, as wise and kind a person as I've ever met. He had a relaxed way that could instantly put people at ease, a quick mind and disarming sense of humor. When attending events in Lou's honor, he would gracefully skirt the limelight. But at the drop of a hat Bill could break whatever ice there was, and his incisive remarks would invariably demonstrate that he was more than the genius' better half. "Bill always knew who he was," Lou said during a drive to San Francisco one month after his lover's passing. "When we were together in public, he knew the importance of what we had done, even when others did not." Bill eschewed attention; formality meant little to him. It was the actual "doing" that counted, and he was aware that he'd made indelible contributions to Western music history through his creation of beautifully resonant instruments. AT BILL'S APRIL 16 memorial, Charles Hansen, Lou's personal assistant and archivist, read from Bill's autobiography-in-progress (written at age 12). In addition to precociousness and wit, Bill's writing revealed an incredible sense of self-assurance. Raised in Weed, Calif., near the base of Mount Shasta--which he climbed a dozen times during adolescence, often alone--Bill was the third-born of Donald and Star Colvig's six children, and oldest of their four boys. Like his siblings, Bill took up music at an early age. His father, a local bandmaster, made music a staple of the Colvig household, and he inspired all of his children (Claire, Donna, Bill, David, Richard and Ray) to take up musical instruments. Bill played four: piano, trombone, baritone horn and tuba. Bill also had a knack for things mechanical. He fixed engines, toys and tools and invented new ones. He rigged up massive antenna structures and placed them on buildings and treetops so that his family's radio could pick up San Francisco&-based classical music broadcasts. He reconfigured a 78rpm turntable so that it wouldn't require winding up. And, of course, he kept all the vehicles in running order, especially a 1923 Chevy touring car the family called "Bill's crate." Although a music scholarship brought Bill to the University of the Pacific, he was drawn most to the courses in electrical engineering. He furthered his studies on the subject at UC&-Berkeley, and in Fairbanks, Alaska, he worked as an electrician, which became his life trade. Music-making would continue, but on a purely for-pleasure basis. Three of his siblings went on to have professional careers in music: David became principal flutist for the Houston Symphony; Donna, an accomplished jazz pianist; and Richard, a music librarian and organist. Bill, though, wanted to see the world. The electrical trade optimally served Bill's wanderlust. During his time in the Army signal corps during World War II and afterwards on his own, Bill pulled wire and explored spectacular landscapes throughout the Middle East, Africa and South America. He was a quintessential gallivanter, keenly observant of the world's diversities and ever eager to experience them firsthand. I always enjoyed listening to Bill reminisce about his travels because his inclusion of unusual details--weather, geography, quirky individuals and, of course, music--made the descriptions especially vivid. After the war, Bill re-enrolled at UC&-Berkeley, joined the Cal Band and became an avid appreciator of the Bay Area's diverse cultural expressions and entertainments. He surely dated a lot, too. Bill had the chiseled good looks of a leading man, and San Francisco wasn't a bad place to be gay in the 1940s and '50s. To provide a sense of the life Bill lived, Charles Hansen dug out a couple of pages of Bill's calendar from the late 1940s for me to peruse. From early childhood until his final year, Bill scrupulously recorded his itineraries (and later, Lou's as well) on hand-drawn 8 1/2-by-11 calendar grids. Entries between January 1948 and August 1949 encompassed a typically eclectic mix of cultural events and social activities--climbs on Mt. Diablo on Jan. 25, 1948, and the Pinnacles on Feb. 21, 1948, the Ballet Russe performing Aaron Copland's Rodeo on Nov. 23, 1948, the movie Key Largo on Oct. 15, 1948. In 1949, there was Tuolumne Meadows, a screening of Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and a performance of the musical Kiss Me Kate, to name a few entries. There were climbs year-round, in fact, as a hike leader for the Sierra Club. Bill led hundreds of them over the years. Between working full time as an electrician, hiking on weekends, concert-going and the like, Bill still found time for musical intimacies at the piano, sight-reading baroque and classical literature, and--like his father--filling in with amateur concert bands on whatever wind instruments were needed. There were family jams, too. Living in the Bay Area afforded Bill extra playing opportunities because several of his siblings lived nearby, and Colvig get-togethers usually included music-making. They still do. I remember Lou recounting with amazement (and amusement) the vigor and expertise that Bill and his siblings displayed when playing together at the Colvig family reunion last year, which turned out to be the last time that the entire family was together prior to Bill's passing away. Lou's presence at Colvig gatherings was never rare; he'd long been considered one of their own. Ray Colvig (youngest of the four brothers) explained in a phone conversation that his family had been happy for Bill when he and Lou met in 1967. At age 50, Bill seemed truly happy. And very much in love. "Bill went through lonely times after the war," Ray said. "Meeting Lou opened up entirely new worlds for him, and for us. ... Lou is like a brother to me."

LOU AND BILL'S MEETING after a performance of Harrison's music at the Old Spaghetti Factory proved pivotal for both men. Lou's immersion in Asian and Indonesian music struck a chord in Bill; the sound world he'd encountered abroad had made a deep impression on him, and the composer's music brimmed with ethnic echoes from outside the then-fashionable Eurocentric orbit. For three decades Lou had been scouring junkyards and hardware stores for objects of specific resonant qualities to use as instruments. He now felt a need to build new instruments, precisely tuned ones, maybe even an entire orchestra of them. For Bill, the notion of instrument building--with a bare-bones budget--was exhilarating. He had always thrived on challenges, and bringing Lou's sonic ideals to fruition required a thorough melding of his mechanical ingenuity and musical ear. The joys of musical communion that Bill had experienced with his family were newly kindled with Lou as they learned to play many of the instruments they built. Both developed competency on multiple instruments of Indonesian, Chinese and Korean origins. Bill's experience as a brass player made him a quick study for wind instruments, and I recall particularly his tender playing on the sheng, a Chinese bamboo mouth organ. During the 1970s, Bill, along with Lou and musician Richard Dee, presented over 300 concerts of Chinese and Korean chamber music to grade school children throughout the Bay Area. I came to know Bill through my association with Lou, as did many a young composer. After all, Lou's fame had been worldwide for a quarter-century when I first visited him at San Jose State University in 1976, and Bill was already helping moderate the incoming flow of up-and-comers on the home front. I remember waiting for the sound of footsteps while standing on the porch of their little Aptos cabin, wondering if I should comment on the "Love Your Mother" poster that hung in front of me. Bill opened the door and greeted me with a slightly bemused tone and added with evident suspicion, "So you're the fellow who wants Lou to write this piece of music." And then, dimenuendoing afterthought: "It's a lot of work, you know." I was only slightly intimidated by Bill's remark; he was the most charming gatekeeper imaginable. A rugged "man-on-the-mountain" exterior (a worn Pendleton shirt, khaki shorts and hiking boots) was offset by a tuneful, sotto voce delivery and an easy smile. In fact, as Bill came to know a person better, his pronouncement of their name would settle into a melodic gesture (based on the vowel contour) which he would half-sing in greeting. Mine glided downwards, almost an octave sometimes. And then there was the punning. Bill was incurable and unusually swift. He delighted in springing puns and punch lines on the unsuspecting. He had a puckish quality, or maybe a little bit of coyote. But Bill spoke his mind unflinchingly. He would be tactful, but never false. There were cantankerous moments, times when Lou and Bill bickered like an old married couple--which, of course, they were. However, the basis of their love was one of the strongest and most enduring I've seen. Their common ground covered acres compared to most couplings. In addition to their musical links, both were indefatigably supportive of organizations that championed human rights and ecological preservation. Prior to meeting, each had been supportive of radio station KPFA, which since its inception has been a broadcast bastion for gay rights and social justice. Bill was particularly devoted to listening to KPFA's morning and evening news programs, which were heard at the Harrison-Colvig household with the regularity of Catholic lauds and matins services. Reading aloud was another of the couple's cherished daily observances--there were many daily routines. Weekly ones also. The Sunday routine began with their resplendent waffles-and-eggs-breakfast and ended in the evening at Manuel Santana's restaurant above Seacliff State Beach in Aptos for margaritas and enchiladas. I WAS THRILLED when Bill, in 1978, phoned to invite me over for Sunday breakfast. I had recently begun working as Lou's copyist, and the opportunity of socializing a bit with Bill and Lou was a welcome, if unexpected, prospect. The meal, which they jointly prepared, was of banquet proportions: a lavish spread of eggs, waffles, assorted fruits, stewed prunes, jams, syrups, juices, coffee and more. Lou and Bill delighted in pampering their guests, and their hospitality routinely included hosting out-of-town friends and colleagues who were passing through or visiting. I can't remember exactly when Bill began calling me "Dapper Dan," except that I was probably wearing an ill-fitting suit at the time. Bill coined nicknames for a number of friends, and although mine was originally reserved for the times I donned formal attire, I was Dapper Dan more often than not during our final encounters. Throughout most of my last visit with Bill, I read aloud to him from O. Henry's Strictly Business: New York Stories. Despite his weakened (and medicated) state, Bill made faint chuckles and hmms at the narrative's bright spots. Late in the afternoon two days after my visit with Bill, I received a call from his and Lou's close friend Frank Foreman, warning me that Bill's time to die was close at hand. It was too close. By the time I got to Bill's room at Pacific Coast Manor, he had passed away. After saying my goodbyes to the body that I'd known as William Colvig, I helped Lou, Charles and composer Robert Hughes (a former student of Lou's and Lou's sole arranger and orchestrator) pack up our friend's few belongings, which we had brought to the rest home to brighten his stay there. Essentials included a transistor radio (for news reports) and assorted pieces of Mexican folk art on the walls and table tops. They were just a glint of the nearly completed redecoration of Bill's room at home. "We Mexicated it," Charles said. In anticipation of Bill's return home, Lou and Charles had painted his bedroom in vibrant primary colors, which, together with several carved-wooden icons, created a festive Mexican atmosphere. Although Bill didn't live to see his room's Mexication, its radiance endures as a loving tribute in his memory. And Bill's beautiful instruments still resonate; they will continue to do so for many years--and ears--to come. [ Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the August 9-16, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Eclectic and Electric: While working full time as an electrician, Bill Colvig also managed to craft unique musical instruments and to master the Chinese sheng, which he played in impromptu jams and landmark concerts.

Eclectic and Electric: While working full time as an electrician, Bill Colvig also managed to craft unique musical instruments and to master the Chinese sheng, which he played in impromptu jams and landmark concerts.