![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[MetroActive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Court Intrigue

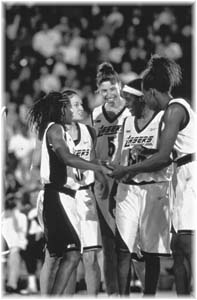

Photo by Aric Crabb

From nada to a wealth of riches--what took women's pro basketball so long to elbow its way into the big boys' spotlight?

By Ellen Farmer

WOMEN'S BASKETBALL--IT'S everywhere you turn. First the U.S. women's team, coached by Stanford's Tara Vanderveer, clinches the 1996 Olympic gold medal after a year of exhibition games. Building on that momentum, the American Basketball League (ABL) emerges the following winter season. Each of eight teams, including the San Jose Lasers, features Olympic and collegiate stars. Then the Stanford women's team comes within points of winning the NCAA final four in April. And, this summer, we have the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) on TV.

In a Santa Cruz Parks and Recreation summer league, we also have 12- and 13-year-old girls putting everything they've got into the game of basketball. No shrinking violets these, worrying obsessively about clothes and diet, they tilt back their water bottles between halves, sweating and laughing, fully embracing the vigor of youth. What's the big question on their minds?

"Will Jennifer Azzi be at the Lasers' basketball camp this August in Santa Cruz?" asks one.

"I have her autograph from the first Laser game!" says another, as starstruck as my generation was by the Beatles.

"It's not a product, it's a movement" is the ABL motto. At the 25th anniversary of Title IX, upheld last April by the U.S. Supreme Court, professional sports opportunities for women are finally a reality. Skills once taught to sons to ensure adult success are now also passed on to daughters.

"You learn how to compete. You learn teamwork. Women have a right to develop those qualities as well as men," says Lynette Woodard, two-time U.S. Olympian and the first woman in the Harlem Globetrotters. At age 37, Woodard has returned to the game to play for the WNBA's Cleveland Rockers after several years as a successful stockbroker. Pro women's basketball finally caught up with her.

Some of the WNBA-TV commentators need to catch up with the '90s, however. Often they seem to get tongue-tied trying to describe great moves by strong women. But turn down the sound, and you can catch some good, clean ball. "Some of the best and purest basketball played today is among the better women's teams," says former UCLA coach and present Hall of Famer John Wooden.

Despite the poor commentary, there are two great things about the WNBA's coverage this summer. First, it keeps people interested in women's basketball year-round. Second, viewers are barraged with a heavy dose of well-produced commercials and player bios. Even though they overemphasize the femininity of WNBA athletes (a little homophobia at the storyboard, perhaps?), one commercial after another depicts smart, strong, confident women as big-time stars.

The opening game of the inaugural ABL season was played before a sold-out crowd right in our own back yard at the San Jose Arena. Former Olympic teammates Jennifer Azzi of the Lasers and Teresa Edwards of the Atlanta Glory gave each other a spontaneous hug before the tip-off, then battled each other with unqualified zeal all the way to the final buzzer and a San Jose victory.

It was a historic moment. Being able to play professional sports for $50,000 to $120,000 a year is a very visible measure of the success of the women's movement. It represents a great new opportunity for the coming generation, confirmed by the fact that 570 women tried out for 80 spots in the ABL.

"I love the physical play," says Noel Trepagnier, who's either been a softball player or ump for 25 years. "If you're gonna go inside, you better be prepared to get it. That's the game of basketball.

"A lot of us old jocks have been raised on men's sports because that's all we had," she continues. "Now I watch the young fans of women's pro ball, and they can't get enough."

And there are whole basketball teams of uniformed kids fresh from practice at each Lasers game. Groups of 10 or more get their name displayed on the electronic kiosk at halftime. Ticket prices are reasonable (anywhere from $5 for front-row seats in the bleachers to $35 courtside) and, except for a few games like the season opener and playoffs, tickets are usually available.

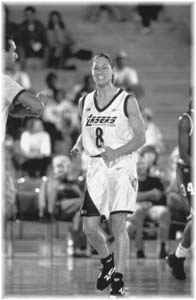

Photo by Aric Crabb

Then and Now

MARY O'NEILL was selected "Most Outstanding Player" more than a few times at her Catholic high school in Fremont during the years when the details of Title IX were still being hammered out. She's such a Stanford women's team fanatic that she once spent a whole day of her vacation driving all over Kauai trying to find a sports bar where they would show the NCAA women's final four rather than the men's. She predicts the women's pro leagues will thrive because the tide has turned.

"When I was young, I was always as competitive as the boys," O'Neill says. "That made me different. People called me a tomboy, and I hated it. I would correct them and say, 'No--I'm a girl who wants to play sports.'

"The pro women's leagues will flourish because of the talent being developed from junior high on up," the Santa Cruz house painter says. "The girls will require professional opportunities."

O'Neill describes her friends shuttling their daughters to games all over the region with a wry smile. "They have uniforms and good shoes, serious coaches and plenty of girls to make a league. I wish someone had taken me aside in high school and helped me develop my skills, but there was no opportunity to go on."

On U.S. soil, that is. Although basketball is the one major sport strictly of American origin (it was invented by James Naismith in 1891 at the YMCA in Springfield, Mass.), for decades women have only been able to turn pro by leaving the country. Female leagues thrive today all over Europe, Asia and Latin America, and they offer big bucks to U.S. women players.

Throughout the 1930s and '40s, crowds gathered regularly to watch women play. The AAU--Amateur Athletic Union--consisted of teams sponsored by companies such as Hanes Hosiery and Dr Pepper. The All-American Redheads were an exhibition team much like the Harlem Globetrotters. Before TV, women's basketball often drew larger crowds than men's, according to Elva E. Bishop's documentary Women's Basketball: The Road to Respect.

But in 1953, the North Carolina legislature outlawed the girls' state competition for white high schools because they feared high-level competition was dangerous to the physical and psychological health of young women. In order to even play the game at school, girls had to follow "girls rules," which called for six players, two of whom had to remain in the back court, with only two dribbles per player before a pass. These restrictions spread like wildfire.

American women's teams couldn't hope to compete overseas if they couldn't practice a more competitive game. Due to the sexism of the 1950s and '60s, women's basketball was placed on the back burner. With the advent of television coverage, basketball appeared to be a man's sport.

"These pro women's leagues are long overdue," says peace worker and "lipstick feminist" Kathleen Hughes, who was surprised to find herself yelling from the bleachers at the San Jose Arena last winter. "I'm not an athlete--never cared about sports. But watching these women players and coaches excel on the court is a real inspiration."

For Hughes, basketball has become one big metaphor for how people face life's challenges. "We all have struggles in life. It's easy to over-analyze everything and get discouraged," she says. "In basketball, the great players get back on the court and give it their best. The great coaches use their intelligence to create new strategies on the spot. I need to be tougher like that myself."

Contemplating the purchase of Lasers season tickets and the questionable coverage of the WNBA, Hughes adds, "I want the ABL to make money and thrive. I hope it doesn't have to sell its soul to the circus to get there."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Goodness Gracious--Great Balls of Fire: The smiling, dribbling, passing, three-pointin' San Jose Lasers are the South Bay's first professional women's basketball team.

Azzi Oz-Borne: Former Stanford star and present Lasers playmaker Janet Azzi was a big reason why women's pro basketball finally reached over the rainbow to become a real player in the boys' club world of major sports.

The San Jose Lasers are sponsoring basketball camps for kids Aug. 1114 at the Santa Cruz High gym (call 271-1500 for details). Local fans also can greet the two new Lasers coaches, Angela Beck and Bobbi Morse, at a public rally and reception from 4:30-5:30pm on Wednesday, Aug. 13, at the Santa Cruz Hotel Sports Grill (Cedar and Locust streets). Several players will be on hand to sign autographs and a raffle for game tickets and T-shirts is planned.

From the August 7-13, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.