![[Metroactive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Take the Morsel And Run

The American obsession with spending as absolutely little as possible on dining has finally hit bottom

By Christina Waters

HASN'T ANYONE ever heard the expression "You get what you pay for"? Well, you do, and never more so than in the case of food, where mediocrity is invariably signaled by rock-bottom prices.

It constantly amazes me that people who think nothing of dropping $200 on a Donna Karan tank top will balk at the thought of spending $7 on a salad of organic lettuces. What are they afraid of? Great flavor? Health? These same shop-till-you-drop bargain hunters will carbo-load on indigestible, preservative-laced burgers ("they're only two dollars") while trying to keep ketchup stains off their designer jeans and Coach purses.

Hypocrisy aside--wasn't it Star Trek's Data who observed that human behavior is rarely consistent--there's something flat out mindless about this obsession with cheapness at all costs. Where did it all start? Was it the day that the very first discount house opened and convinced millions of Americans that greed was part of Walt Disney's plan? You could really stretch your dollar at one of these discount stores, coming home with (and this is the operant phrase ) more stuff than you'd ever dreamed possible.

In a capitalist culture, quantity is not only equated with quality--it shoves quality right out the door and down the River of Compromise. We want lots and lots of whatever the commodity is and we never once question whether what we're getting so cheaply is worth having. (Somewhere in here I can hear Socrates mumbling that the unexamined life is not worth living.)

There are several swollen strands to this issue of cheapskate dining. One is the tendency to equate value with portion size. "The more money I spend, the more damn steak I want to see on my plate"--that sort of thing. But even more unsettling is the tendency to not want to spend money on disposable, intangible experiences, i.e., when you're finished with a fine meal, there's nothing you can take home and put on your mantel. But when you've made those three easy payments of $29.95 each, by God, you get a 24-karat gold-plated hand-painted commemorative plate of Amelia Earhart. You can put it in your den. You can look at it. Your neighbors can look at it. It's tangible, solid, material. Now that's money well spent, we think, never daring to indulge in something that occupies only psychological space.

Point is, if we can't hold what we've purchased in our hands--or more importantly, show it off to others--we don't actually believe that it's real. And that's one of the reasons why we are so reluctant to part with money for life-affirming experiences like romantic overnights, spiritually renewing journeys to places we've always dreamed about, and, yes, utterly enjoyable two-hour dinners during which we don't have to cook and after which we don't have to clean.

It's only food, I hear some of you saying. Right. And vacations are only obligatory absences from home.

The Cheapskate Olympics

My father and uncle are tied for first place in the All-Time Cheapskate department. They both love dining out. They both love dining out when they don't have to actually use their own credit cards to do so. But mostly, they love dining out at places that are dirt cheap.

It's not, however, just their Depression Era generation that loves to spend the least possible amount on food. (But it's true, these are the folks that keep the "all you can eat" King's Table mentality in business. "All you can eat"--think about the sheer piggishness implied by that phrase. It takes the breath away.) Younger Americans are cheapskates, too.

People ask me all the time where they should go for a great meal. When I rattle off the names of a few reliably fine restaurants, they gasp, "But aren't they expensive?" I always lose patience with this attitude. There are no free lunches. You want greatness, you should be willing to pay for it. But the fact of the matter is--pay attention--that you can easily spend just as much on a meal at a so-called inexpensive place as you can choosing wisely at a so-called expensive place.

A recent lunch at a self-serve, family-friendly restaurant reinforced the point that cheapness is never a good deal. This dining room had all the atmosphere of a state prison, high school cafeteria and day-care center rolled into one. Screaming children and banging dishes filled the air. We paid, we waited, we picked up our orders, got our own silverware and applied our own condiments. As we considered our $7 sandwiches prepared with spartan dullness in this ambience-free zone, one male companion murmured something about his college dining hall being cheaper than this. No frills, no atmosphere, no service--and no pleasure.

It's true we didn't have to tip our waiter--whoa, maybe that's it. Maybe we feel we're being fleeced when we tip the hard-working server who explains the menu, brings us extra bread, serves the various courses, clears the table, etc., etc. Maybe we feel that we're somehow being tricked out of our money when it comes to tipping. That's why people like their drive-through fast food experiences. Back to the state hospital lunchroom.

For that same $7, I could have been having a nice plate of pasta in a noninstitutional setting. Or an interesting, handmade sandwich on great bread at a favorite downtown wine bar. Point is, you can do a lot better than this slop you're settling for. Downscale, generic dining isn't necessarily cheaper. It just feels that way.

Das Bloat

Back to the issue of portion size. "You really get a lot of food," people insist defensively, in an effort to explain why they continue to frequent mediocre eateries they don't even like. "But you get so much," I've heard people enthuse of a meal that gave them heartburn and indifferent service.

Why is quantity the issue? Because we enjoy being the most overweight country in the world? Because we're painfully insecure and desperate to wrap our mouths around the reassurance we fail to find in our marriages, careers or friendships? What is this pig-out consciousness that has dried up consumers' ability to do the simple math--quantity does not guarantee quality. Worse, people seem not to care about the quality of what they eat at all. Is this a self-esteem issue? I'm not good enough to eat something with a knife and fork. Only fit for cheap, greasy, amorphous stuff I can grab with my hands and stuff down my throat.

The need to get really full for not much money is destroying what's left of our self-respect. We are what we eat, and that means that we are turning into a flabby mass of processed salt and fat. Culinary con artists looking for a free meal. Why do we cheapen the quality of our lives in an effort to eat cheaply? Life is too short to keeping making a deal with dignity. Every day of your life matters. Get out of the trough and treat yourself with some respect.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

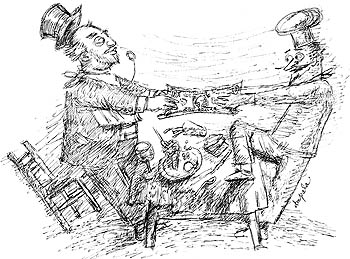

Illustration by Impala Corona

From the August 7-14, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.