![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Sacred Outing

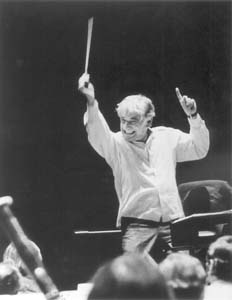

Dramatic Downbeat: As a composer and as conductor of the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein had a flair for the dramatic that comes through in the themes and music of 'Mass,' the opening production of this year's Cabrillo Music Festival.

The Cabrillo Music Festival comes of age with an ambitious production of Leonard Bernstein's 'Mass'

By Rob Pratt

GEORGE SANTAYANA left out an immensely important corollary to his maxim "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." What he didn't say is that the past sometimes repeats itself anyway. It's a cruel irony that John F. Kennedy Jr. met an abrupt end mere weeks before the Cabrillo Music Festival presents Leonard Bernstein's Mass, a work commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy to memorialize her first husband, Kennedy's father.

"Like his father, he had a real hope for people," says Douglas Webster, director and featured soloist for the Mass. "He wasn't playing with the public's affection for him, and he didn't have to sell pieces of himself. Though we're not going to put him into the production, he'll be there in all of our hearts."

History also repeats itself in marking a cultural achievement with Bernstein's Mass. Taking on such an ambitious production represents a coming of age for the Cabrillo Music Festival and Marin Alsop's tenure as music director in the same way as the premiere of Mass 28 years ago marked a national cultural landmark, the inauguration of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

As an indication of the enormity of the production, co-executive director Ellen Primack says she expects the festival budget this year to approach $400,000--fully a third bigger than the nearly $300,000 budget the festival has averaged in recent years. Even more than that, Mass director Webster (who also plays the celebrant, the lead character) explains that the show stands to lose money on the production even under the best of conditions.

At this point, Primack continues, fiscal concerns about taking on a major production came second. For Alsop and festival organizers, Mass represents a point of artistic growth, a necessary next step if the organization as a whole is to advance in sophistication and achievement.

"It's really an artistic decision--the festival has to push itself artistically," she says. "And when everything is put together and everyone sees the Mass, you'll know exactly why we did it. That's when we will indeed break even."

A CabMuFest mini event calendar

Mixed Measures

MEASURED IN terms of artistic achievement, the festival has almost continually moved forward since its beginnings in 1963 at the now defunct Sticky Wicket coffeehouse in Aptos. And it has always put music first: the immediacy of the contemporary and the shock of the new.

Under the spiritual guidance of Lou Harrison, who with Robert Hughes organized the very first concerts, the Cabrillo Music Festival at the turn of the millennium can count among the composers it championed over the years easily a dozen whom history will record as the most important of the century.

A mentor of Alsop's and a prolific contributor to popular music as well as to the symphonic repertoire, Bernstein made major contributions not just as a composer. Though Bernstein was certainly a man of his times, the musical polyglot that is Mass probably speaks to audiences more effectively now than it did at its premiere.

Mixing musical languages--sections of the 105-minute piece include a folky hymn, Esquivel-like vamps, odd-meter dances, instrumental solos, klezmer strains, rock songs and the irreverent song "God Said," seemingly snatched from a Jesus Christ Superstar-era Broadway show--appeals more to turn-of-the-millennium audiences than it did in 1971 (when Time suggested Bernstein's approach "reflects a basic confusion").

"Bernstein was one of those people who started the ball rolling in that direction by writing so much excellent popular music for orchestra," Alsop says of recent trends toward stylistic mixing. "He was blurring boundaries, and it ends up now being part of our culture."

For 20th-century music, technological advances and the search for a unique American idiom have meant an expansion of the language of symphonic music. At the time Bernstein's Mass premiered, Alsop says, few composers attempted to mix styles within one piece. Now the idea that a work of symphonic music could be influenced by rock & roll is not at all outrageous.

"It's less obvious with time--more abstract," she says. "It's literal at first. Composers impose other styles on the symphony. Then they learn that one can take the essence of it and not all of the particulars. The key to combining music successfully is to develop a style and vocabulary that are not derivative and evocative of something particular."

Other beats at the CabMuFest

Learning by Listening

TWENTY-EIGHT years later, Mass seems a prescient foreshadowing of the direction of new music at the end of the 20th century. But it also holds up as a fitting emblem of the Cabrillo Music Festival. Virtually every major composer of the post-World War II years has earned a featured spot on a festival program (and many have spent a season in residence).

The "Giants in Concert" offering (Sunday, Aug. 8), following the season-opening presentation of Mass, neatly encapsulates those themes. Three of the featured composers--Aaron Copland, John Adams and Christopher Rouse--have spent seasons in residence.

Though best known for his picturesque works using pioneer and Wild West themes (Appalachian Spring, Rodeo, Billy the Kid), Copland later in his career turned to less overt Americanism in his music, aiming for a more subtle and mature expression of national themes.

Though Alsop doesn't highlight the fact, Connotations for Orchestra (on the program for Sunday's concert) parallels Bernstein's Mass. Both were commissioned to honor the opening of a most important American cultural center--Copland's Connotations for New York's Lincoln Center in 1962 and Bernstein's Mass for the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., in 1971.

Like Copland, Rouse privileges expression of emotion in his music over almost any other consideration. Though he studied piano and percussion when young ("It didn't take," he admits), he declares that he's not at all an instrumentalist.

"Indeed, some of the best orchestrators have been some of the worst instrumentalists," he adds. "It forces you to hear in a different way and to work in a more interior fashion."

Before the technological advances of the 20th century, Rouse says, few noninstrumentalists could learn advanced composition and orchestration. Students had limited access to performances of master works. As a substitute, they could listen to important works in "piano reductions," or digest versions of symphonic works written for the piano--if they could play the piano. The invention of audio recording changed all that.

"I have an electronic keyboard that I do occasionally use, but that's pretty much it," Rouse says. "Any good composer should have a well-developed ear, and I was lucky that I started early and, not being an instrumentalist, by osmosis found my way through listening."

Rouse says that learning composition by listening instead of by playing has freed him to write what he hears instead of what he can play. His themes, however, are colored by a vastly different world than his mentor Copland worked in--a world well into the Information Age and perhaps with more aggressive attitudes about personal achievement. A baby boomer who grew up with rock & roll, Rouse translates his experiences into compositions both rhythmically complex and beautifully melodic, both lyrical and brutal in dynamic.

"A piece can have all the technique in the world, but if it has no expression, then it is doomed," he believes. "I really believe in the idea of expressive urgency--not only on an emotional level. It has to have some technical accomplishment. It has to have something to say and say it with a sense of passion."

In works featured at festival concerts (like Gorgon from the 1995 season and Symphony no. 2 done last year), Rouse expresses dark ideas often associated with death. Though at times brilliant with motion or soaring on a strong melody, his Flute Concerto (to be performed Sunday) also takes up dark themes, memorializing in the middle movement James Bulger, a two-year-old British boy murdered by a pair of 10-year-olds.

"Some people have associated dark themes with me--death," he says. "It was just that for six years every time I had a commission, it seemed there was a death that was important to me. The last few years my music has run more to the light than the dark."

Ultimately, he continues, the main point is to express one clear idea. "I don't like to shilly-shally around ... and usually there is a clear, expressive message," he says. "I'm blessed that I feel from audiences that they do understand what I'm trying to say."

Bernstein's Faith

THOUGH ALSOP has taken a look at prevalent ideas in contemporary music with her programming for the festival, she has generally shied away from grand themes, preferring to let the composers deliver their own messages. The message this year, though, comes through clearly with Mass:

"Bernstein had a faith in the concept of humanity, that we're all connected and the idea of integrating things together," Alsop says. "That's what Mass does--there are so many forces involved. By working on the piece you create a microcosm of what Bernstein was striving for in the world."

By getting to a point where it could stage a production of the grand work, the Cabrillo Music Festival also mirrors the world of Bernstein's Mass. It has faced a fiscal test of faith, endured an identity crisis and emerged with an optimistic vision of the future. Led by Alsop, who's lately gaining a much-deserved reputation as one of the finest conductors of her generation, the festival stands to meet the 21st century as a national showcase of a booming scene in contemporary American symphonic music.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

The Carson Office

The Carson Office

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the August 4-11, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.