![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Victorian Vigor

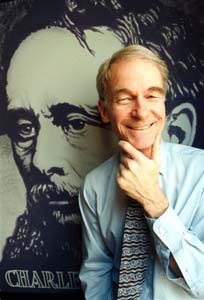

To the Victorian Go the Spoils: John Jordan wants the world to know about Dickens.

UCSC's Dickens Universe explores the novelist's obscure object of dissent, 'Barnaby Rudge'

By Richard von Busack

WHO READS Charles Dickens anymore? I see that the Bantam edition of David Copperfield is still in the Amazon top 150,000 (#142,275)--but most students are keelhauled through Copperfield one way or another. Dickens, however, intimidates many casual readers. He's in danger of becoming admired without being read, after decades of being adored wherever English was spoken.

Dickens survived a literary wave of backlash right before World War II. Aldous Huxley deemed him "vulgar." Worse was the Twilight Zone-ish sequence in Evelyn Waugh's satire A Handful of Dust, in which it is proposed that hell is a place where you have to listen to Dickens read aloud for eternity.

Only relatively recently--the last 30 or 40 years or so--has Dickens been considered serious enough for scholarly study. His old-fashioned, brambled plotting, his by-the-pound writing, his heavy, quaint use of caricature, most of all his very popularity--all ensured that Dickens might not be welcome in the academic pantheon. Now that's changed; the study of Dickens is almost a humanity department in itself. UC-Santa Cruz, for instance, houses the Dickens Project, a major center for the dissection of all things Dickensian. By contrast, the general population knows its Dickens mostly from film adaptations. His most popular character is Ebeneezer Scrooge--it's as if Ella Fitzgerald were known only for her Christmas albums.

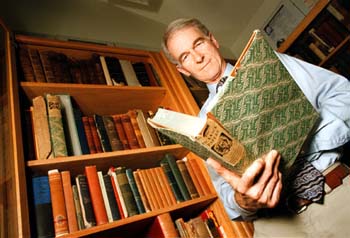

Is Dickens becoming a writer for other writers? Novelist Nelson Algren was asked by journalist Studs Terkel what he felt he'd lacked in life, and Algren answered, "A leather-bound set of Dickens; a writer ought to have that." Algren was right. Such a thing is an indispensable writer's tool--all you'd need on the desert island with the Shakespeare, the OED and the portable typewriter. One hopes "leather-bound" means an edition as it once was, with the longer novels broken into volumes.

When Dickens is read today, readers too often take a big forced march through a cheap paperback edition, complete with microscopic print and cramped leading. Most of the used Dickens volumes I see at friends-of-the-library sales are portable ones: leather-bound but smaller than the tiniest trade paperback. One that I bought on Charing Cross Road was a decayed, green-leather, tissue-paper copy of A Tale of Two Cities meant to be shipped out to India for the overseas British. Reading an edition of that size takes either devoted love or the threat of a low grade. Too often, for students, reading Dickens is a task, then a drudgery.

A Universe in a Book

EVEN JOHN JORDAN, the English professor who leads UC-Santa Cruz's Dickens Project, admits that bringing a modern, short-attention-spanned student to Dickens is a daunting pedagogical task.

"It is difficult to teach long books of any sort," Jordan says. "Dickens published his novels as serials. They weren't intended to be read in one sitting. When students realize that, it's a little easier for them. Sometimes I put a prohibition on reading ahead in the novel, explaining that what Dickens is doing it like a TV serial."

Dickens study has just been made easier by the editors of the Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens (654 pages; $45), in which 60 scholars contribute essays on every aspect of Dickens, from childhood poverty in a shoe-polish factory to adult celebrity at Gad's Hill in London. Full of trivia, great themes, contemporary photographs and biographies, this compilation is the best study of Dickens in many years.

Closer to home than Oxford, the Dickens Project mounts its 19th-annual Dickens Universe, a week of workshops, panels, film screenings, lectures, performances and "Dickensian conviviality" at UCSC, starting Aug. 1. It's certainly not just a boot camp for reluctant scholars, although the lineup this year is impressive: among the guests are Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, authors of The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), an important feminist critique of the portrayal of women in Victorian fiction.

Jordan explains that the Dickens Universe provides a chance for academics and Dickens fans to mingle. "One of the things that is very special," Jordan says, "is that [the event] brings together people from all backgrounds. We have Elderhostel groups and 12-year-old boys, high school teachers, lawyers and social workers as well as world-class scholars. It's unique--a cross between a conference and a festival."

Get a Grip

EACH YEAR, the Dickens Universe focuses on a single book. This summer's main topic is 1841's Barnaby Rudge, Dickens' fifth and perhaps least-loved novel. The Oxford Guide claims, "Barnaby Rudge met with little favor in its day and (with notable exceptions) that judgment persists."

It's a formidable historical novel about the religious and civil strife of the late 18th century that culminated in the Gordon Riots of 1780. The ambitious work was as much trouble for Dickens to create as it is for casual readers to absorb.

"One of the reasons it was difficult," Jordan notes, "is that Dickens was writing the novel in weekly installments. The chapters are shorter, and he's more comfortable when he has more room to develop. Dickens said he was 'writing in teaspoons instead tablespoons.' "

"One generalization I could make about the Dickens Universe," Jordan adds, "is that the best universes are on the most obscure books. We had a very good one on The Old Curiosity Shop. A lot of people find the eccentricities--their weirdness--of Dickens' early novels appealing," Jordan notes.

"People who give Barnaby Rudge a chance find that they enjoy it," the professor continues. "For example, Poe liked Grip the talking raven, using a similar bird for his most famous poem. We're going to have one lecture comparing Edgar Allen Poe's raven and Dickens' raven. It's said that Poe read the early installments and, based on some of the things Grip said, predicted how the novel was going to come out."

Yep, Grip is a fine bird; he's based on some pet ravens that Dickens himself owned. Barnaby Rudge, however, starts off on the wrong foot, in a slow first 150 pages that set up the drama to come. Once the book enters the hot summer of 1780, it's as compelling as anything Dickens ever wrote--and eccentric and weird enough for any Goth.

Barnaby Rudge's narrative builds to a now-forgotten episode in English history, the Gordon Riots. A brief lesson is in order--no fidgeting. In the first week of the sweltering June of 1780, a demagogic nobleman named Lord George Gordon led a crowd of some 40,000 people to the Parliament. They protested against the lifting of legal restrictions that kept English Catholics second-class citizens.

To be fair, only 100 years previous to the Gordon Riots, the English had chased out James II, their Catholic king, who tried to rule as absolutely as if he were chosen by his God. Two hundred years before the riots was the martyrdom of the Protestants at the hands of Queen Mary I, called "Bloody Mary" (a terrible queen is, ironically, honored by a delicious cocktail).

To Thine Own Shelves Be True: People 'find the eccentricities [and] weirdness of Dickens' early novels appealing,' says Jordan.

Wonderful Gargoyles

BACK TO THE STORY of Barnaby Rudge, an untidy Dickens labyrinth. "Rotten architecture but wonderful gargoyles" is how George Orwell described the more-overgrown Dickens plots. The title character, Rudge, is a powerful but saintly idiot. His boon companion, Grip the raven, has been trained to cry, "I'm a devil."

Another character is Mr. Chester (later Sir John Chester), a skunk by any sobriquet. As Napoleon said of the politician Tallyrand, Chester is ordure in a silk stocking. There's Chester's cat's-paw Hugh, a would-be rapist; and his pal Dennis the hangman, clad in clothes that he got from his dead customers.

For decency to match the decadence, Dickens gives us Gabriel Varden, a locksmith and a bell-hanger. (Bell-hanging is an occupation you won't learn at Heald or DeVry. These were the plumbers who installed bells used to beckon the servants in the mansions of the gentry.)

For the ladies in the house, the novel includes a star-crossed romance. For the men, there is the provocative Dolly Varden, a hotty, a flirt. "The perfect abandonment and unconsciousness of the blooming little beauty," the author comments appreciatively. "Dickens' male gaze at its most suggestive," retorts the Oxford Companion. Yet Victorian readers appreciated Dolly's allure enough to name many things in her honor--everything from popular songs to a breed of horse to a calico fabric to a species of trout.

The story's atmosphere of revolution is mirrored symbolically in the breaking down of the ties between generations. An innkeeper's son, Joe, runs away from his domineering father. And the juvenile Edward Chester is urged by his father to drop his Catholic girlfriend and marry some money fast: "'A mere fortune hunter!' cried the son. ... Returned the father, 'All men are fortune hunters, are they not? The law, the church, the court, the camp--see how they are all crowded with fortune-hunters, jostling each other in the pursuit.'"

Night Cellars

THE NIGHT SCENES of London show a chaos held back only by the sun. The streets are haunted by the creaking of hanging signs--"a strange and mournful concert for the ears"--with armed figures popping out of the murk or, suddenly, runners carrying a sedan-chair, leaving nothing behind them but the sparks of their torches. There are lights, however, from the "night cellars," which open for "the reception and entertainment of the most abandoned of both sexes." Not exactly what you'd see at the Dickens Faire.

When Lord Gordon is rebuffed by Parliament, the crowd goes ape. The soft-minded Rudge is swept up in the anti-Catholic riots; so is Grip, who learns to squawk, "No Popery!" Caught up with the mob--among whose members are "The Associated Rememberers of Bloody Mary"--Rudge and the villains indulge in the looting and burning which left 800 dead. The riot scene tops even Dickens' description of the Reign of Terror in A Tale of Two Cities.

My first impression upon reading this neglected book is how strange it is that it hasn't been filmed since 1915. The book is Dickens-noir, worthy of the lens of a Fritz Lang. One thinks of Lang especially in the early stages of the Gordon Riots.

Dickens writes: "A vision of coarse faces with here and there a blot of flaring, smoking light; a dream of demon heads and savage eyes, and sticks and iron bars lifted in the air." This is an almost exact description of the lynch mob that tries to burn Spencer Tracy alive in Lang's 1936 Fury. The proto-cinematic language of Dickens matches the quick cuts Lang uses to scan the grotesque faces.

This year's Dickens Universe, picking up the historical theme of Rudge, includes a series of films about revolution: the 1936 David O. Selznick version of A Tale of Two Cities, Dr. Zhivago and the Gerard Depardieu version of Emile Zola's Germinal. Also added is what is no doubt the most popular today of all silent films, Lang's Metropolis, which gives a very Dickensian view of revolution, with both sides declaring peace at the end in a spirit of true populist vagueness.

As Dickens wrote Barnaby Rudge, unrest was stirring in England; the Chartists, agitators for the right to vote, threatened the domestic tranquillity. When the book was published, the Communist Manifesto was but seven years away from its debut, along with the Continental revolutions of 1848. Barnaby Rudge is a key to understanding the political ideas of Dickens. In his vivid horror of a riot, the novelist shows himself not a revolutionary but a liberal--untouched by the "smelly orthodoxies" (Orwell again) of the extreme right or left.

On the whole, his sympathies for the poor are ageless. If you think that the current crop of children is lacking in empathy, maybe it's because Dickens isn't read to children much anymore. A modern reader sees that Dickens faces the same social problems that a person in 1999 faces. Unfortunately, the aforementioned reader faces these problems in the same way Dickens did. Check the spellbinding way Dickens wrote about a homeless man in Barnaby Rudge, "a houseless rejected creature," and what a night on the streets entails:

To pace the echoing stones, hour after rejected hour, counting the dull chimes of the clocks; to watch the lights twinkle in the chamber windows, to think what happy forgetfulness each house shuts in; that there are children coiled together in their beds, here youth, here age, here poverty, here wealth, all equal in their sleep ... this is a kind of suffering on which the rivers of great cities close full many a time, and which the solitude in crowds alone awakens.

But what is to be done about it? (In this case, the "houseless" man is a criminal anyway.) Dickens' unforgettable scenes of poverty are, as Orwell noted, flawed by the idea that certain classes deserve the noose, the dungeon and the slum. "Although he [Dickens] is well aware of the social and economic causes of crime," writes Orwell, "he often seems to feel that when a man has once broken the law he has put himself outside human society."

Dickens' novels reflect today's middle-class faith that almost everyone who is in prison belongs there. We can answer Scrooge's rhetorical question: Yes, there are still prisons and workhouses. Even chain gangs are now back in style in America's sunbelt. (On the radio in Phoenix, Ariz., you can get directions to where to see them at work.)

Dickens set an example for us, then, not just to look at the underside of prosperity but to progress beyond mere sympathy to action. His lesson is missed by those who only read as far as the story of Scrooge buying the biggest goose in the market.

Pickwick Symphony

BUT NONE OF THE ABOVE talks about Dickens' humor, which is inimitable. Fretting over this article, I went to a free performance by an amateur orchestra in a suburb near where I live. The recital had been announced in the daily paper, making the event sound very professional indeed.

You'll never know how good an orchestra is until you see a bad one, and this bad one would have been crippled by "Pop Goes the Weasel." The conductor was a wizened, hunched man in a T-shirt. The soloist was an aged lady with a look of panic on her face. The violinists scowled with concentration as they tried to answer the elderly lady's lead.

Outside, a few blocks away, an ambulance siren picked up the refrain, matching the lead fiddle note for note. Only Dickens could have made this particular sort of failure sound funny instead of mean or tragic. The giantess who played the cello, the infirm string section--he would have known how to caricature them while honoring their hard work, their eccentricity, their underdogness. It's a lost art.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

The Dickens Universe takes plays Aug. 1-7 at UC-Santa Cruz. Events are open to the public but call first for details, 459-2103, or check the schedule online at http://hum.www.ucsc.edu/dickens/index.html.

From the July 28-August 4, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.