![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Mobile Homeless

Photo by Christopher Gardner

Between the shelters and the streets , there's a place where some homeless people have discovered they can retain their dignity and enjoy the view--the great publicly funded outdoors

By Traci Hukill

EDITH WILLIAMS IS A PRAGMATIST. While some women in her position would be mourning the loss of a sense of place and belonging, she misses her washing machine. "It wasn't great, but it worked," she says with a good-natured grin. "It beat spending $25 a week on laundry like we do now."

Edith's washing machine is in storage, along with most of her family's other possessions. Edith, her husband, Richard, their five kids and two dogs now share a tent at Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, 130 miles and two months from their last home in Sacramento.

When the family was evicted on June 1 following an act of charity (they took in some homeless friends), the Williamses headed to Santa Cruz, where Edith's sister lives. Now they spend some nights in motels and others in Edith's sister's place. Much of the time, though, they stay in campgrounds.

It's not easy to find a place to camp around Santa Cruz this time of year. The area's state parks, all popular vacation destinations, fill up with weekend reservations months in advance. On the weekends at Henry Cowell, most of the park's 112 camping spots go to travelers who planned their camping trips through Destinet, the state park system's reservation service--not to folks who have resorted to campgrounds as temporary homes. So by the time Edith and her family have just gotten settled into a site, the weekend comes and they have to move.

Her greatest worry is that this lack of stability is having an adverse effect on her kids. In fact, she and Richard chose not to use the shelter system--even though it would be cheaper--because she feared the environment would be too disturbing for the youngsters.

The five kids--three boys and two girls--are polite and well-spoken. The oldest daughter, 14, misses the privacy of her room, but overall everyone seems content. The din around camp is a happy one.

When Richard pulls up in the family van, the kids swarm around to see what he brought from town. He has groceries and a few toys, which he doles out like Santa Claus.

Ironically, this man whose family was uprooted two months ago used to be a homeless advocate. When asked if he's frustrated to find himself homeless, he answers with equanimity, "No, it doesn't bother me, because it puts me back in focus."

Though the family collects AFDC and Social Security for Richard's disability (he has heart problems), the money is just enough to keep food on the picnic table, gas in the van and use fees--$17 a day for state parks, $10 for county parks--paid up. They're looking for a place, Edith says, but with no jobs or savings, and with move-in costs hovering in the thousands, it looks like it will take nothing short of a miracle to get them safely in a house. That's what they're hoping for.

"We're taking this thing one day at a time," she says.

Home Sweet Camp

LAST NIGHT'S WINE-and-mushroom sauce is still sticky in the pan as Linda White* (some names have been changed to insure privacy) eases back in a lawn chair next to her campsite's firepit, novel in hand and dog at her feet. Dressed in stretchy leggings and a bright T-shirt, she looks just like scores of vacationers enjoying Uvas County Park and other parks throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains. She skipped the makeup this morning. She's relaxed and grateful for the peace, happy to not be working today. But Linda isn't on vacation. She and her boyfriend, Glen Roberts*, live here, and this is her day off.

To another camper here at Uvas, Linda and Glen's campsite--with its aging travel trailer and smattering of lawn chairs--might look like any other site. They're sharing a space with a couple from the Midwest, Ken* and Marie*, whose roomy purple tent rests on a springy bed of pine needles. They could easily be friends just getting away from it all for a week.

But a fellow camper on her way to the cinder-block restrooms 50 yards away might pick up on something indefinable about the site as she passed: a subdued sense of calm, the presence of everyday rhythms rather than the blithe chaos of vacation. These four haven't pulled a La-Z-Boy up to the campfire, but they're settled in, nevertheless, and it shows.

"This is a respectable way to be homeless," Linda says evenly, her gaze unwavering. "We're not pushing a shopping cart somewhere. We're not begging for money. We all hold jobs, we all pay taxes."

Well, almost all of them do. Glen, a civil engineer, is in town seeking work today. It's been hard since he and Linda arrived here from Southern California two years ago, but things may be looking up: Not long ago he was short-listed for the position of assistant director of public works in a Bay Area city. Linda herself works as a medical assistant for people who don't know she lives travelling from campground to campground.

"People don't understand," she says. "They look down their noses at you."

Linda and Glen would have been in a house a long time ago, she explains, reaching down to scratch her goofy Rottweiler-mutt's head, if housing weren't so expensive--and if more landlords took dogs. In the meantime she presents a seamless facade of normalcy to most of the world.

Maintaining the illusion of a mainstream lifestyle poses special problems, she explains. You need an address and a telephone number in order to get a job and a job in order to get a house. If you land a job, you need to be able to shower every day, to show up groomed and dressed in clean clothes. That's hard to do in the woods.

Since most of the county parks don't have showers, Linda and Glen use a solar shower bag. They have a mailbox at Mailboxes Etc., which provides them with a street address that looks on paper like a residence.

They use a cell phone hooked up to an answering machine in their trailer so Glen won't miss calls from possible employers.

It's not a luxurious lifestyle, but it's cheaper than a motel and better than a shelter. At $10 a night--and split four ways at that--a space in a county park is the cheapest housing around.

With the money they save they're able to splurge now and then. Last night they even dined on pork tenderloin in mushroom sauce with Caesar salad and wine.

"We eat well because we can afford it," Linda shrugs.

"The human species has made good with cooking over a fire for a long, long time," adds neighbor Ken, who works as a school kitchen manager.

In his early 30s, Ken has an optimistic air about him these days. In less than a week he and Marie are moving into a condominium after doing the campground circuit since their arrival in the Golden State last fall. Just as it serves untold numbers of other newcomers to California, the park system provided the couple with lodging while they got on their feet.

"If I had it all to do over again, I'd do it again like this," he says, popping open a Pepsi from Linda's propane-run fridge.

But Marie, who with her pale, veiny skin and jet-black hair looks like Morticia Addams in jeans and a tank top, is relieved to be leaving this lifestyle behind. Her spacious tent's interior bears the stamp of a woman restless to do some good old-fashioned nesting. It has a tiny bookcase, a houseplant, and a right- angled tidiness that looks almost military. As she files her beautiful nails, which, like Linda's, are manicured but dirty, she adds her piece to the conversation.

"You get crabby every two weeks when you know you're going to have to move," she murmurs.

She's referring to the county parks' summertime 14-day stay limit, a condition imposed to ensure that all the taxpayers get a piece of the park pie. That means small bands like these two couples, who migrate together for security against thieves, are constantly on the move. Linda's an old hand at it by now and knows the ins and outs of the circuit. "You do your two weeks at Grant and Coyote early in the summer," she says, "because it gets too hot there later." Next it's Uvas and Mt. Madonna, followed by Sanborn Skyline. They'll run out of campgrounds before they run out of summer and will probably head to Half Moon Bay to finish out the season.

Linda, Glen, Marie and Ken consider themselves "regular people who ran on bad luck at a bad time." They're friends with the park rangers, they say, and help keep an eye on the place. But they warn that not everyone doing this is desirable company. They've seen people set up ramshackle tent cities in the parks and met families with 10-year-old kids who can't read because they've never gone to school.

For Linda and Glen, the campground circuit may become a long-term solution to the problems raised when a single income meets astronomical rent prices head-on. And although it's better than life in a shelter, the lines in Linda's pretty but tired face suggest that the constant relocating is getting old.

"After two years, I'm tired of it," she admits. "It's hard to stay clean up here. They should have showers." Having obviously put a lot of thought into this, though, she quickly adds, "But then again, they attract people."

Too many people, not enough money. It's the song heard 'round the circuit.

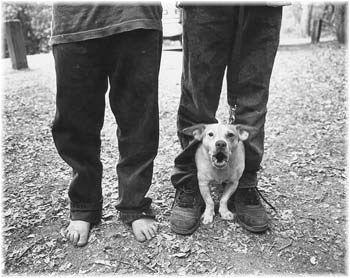

Dog Soldier: Milo the Jack Russell terrier stands guard for a family of seven living at Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park. He barks at the slightest provocation, ensuring the family some safety.

Traditional Householders

PITCHING A TENT WHEN money gets scarce is nothing new. During the Depression Yosemite National Park overflowed with people "camping out" for the summer. "Up until 20 years ago, it was quite common for people to spend the whole summer here," says park historian Jim Snyder. "We had no way to tell who was homeless. Some were doing their normal summer routine, others were living here because there was nowhere else to go. Oh, they weren't dirt-poor homeless. They had to have a car to get here."

A large automobile or an RV, in fact, is often one of the first steps out of homelessness, says Karen Gillette of Santa Cruz's Homeless Community Resource Center. People who are utterly indigent can't usually get to a campground to begin with. And since many of the Santa Cruzbased homeless who camp out in the nearby Henry Cowell and Sunset state parks continue to participate in meal programs, vehicles are doubly necessary.

But not everyone who uses the park system as temporary housing is leaving the shelter system, as Linda and Glen's story illustrates. Many of them are newcomers to the area who can't or don't want to pay $50 to $60 a night to stay in a motel while they look for housing.

As everyone knows, the housing markets in both Santa Clara and Santa Cruz counties are notoriously tight, and move-in costs exorbitant. Two thousand dollars for first and last month plus security deposit for a one-bedroom apartment is commonplace. Add to that burden the sheer masses of people looking for housing and depressingly low vacancy rates (which plunged to below one percent for six months last year) and a grim picture begins to emerge of--what else?--too many people and not enough places.

Sunset Beach State Park Supervising Ranger Stephanie Price has seen it all before. "I've seen the same thing everywhere, from Orange County to Henry Cowell: people camping out so they can scrape together first and last month's rent plus deposit," she says. "We don't discourage them from coming as long as they're paying their fees."

Last spring, a Santa Cruzbased homeless activist group called Save Our Shelters proposed using the state park system to house homeless people. A public outcry against the idea followed. Starting in December, Save Our Shelters placed about 40 people at New Brighton Beach for several months, courtesy of the Santa Cruz City Council and private donors.

"I think it's an appropriate use of our state parks," says SOS organizer Sherry Conable. "But people from all over the country were calling saying, 'Now we can't come to California. We don't want to be next to homeless people.' The state parks had been looking the other way, but when it became a formal program, they did everything they could to stop it."

Bob Culbertson is the chief ranger for the Santa Cruz District of the State Parks and Recreation Department. He's also an active volunteer in the Interfaith Satellite Shelter Program, a consortium of churches which house Santa Cruz's homeless during the winter months. As compassionate as he is toward the homeless, he doesn't see it as the state parks' job to house them. "Our department's main goal is not to provide housing but to provide recreation--to maximize the access people have to lakes or forests or beaches."

Caught between compassion for people in need and the department's don't-ask-don't-tell policy on the subject, most of the rangers remain close-mouthed. It's understandable. Nobody wants to play cop, and besides, people do have a right to enjoy the park system, no matter who they are or what their houses are made of.

Transitional Housing

THE PARKS SYSTEM HAS BEEN a godsend for Greg and Jacque Amdal, a disabled couple in their forties. In May they were living in a duplex in Cupertino when they learned that Greg's benefits, which included half pay while he was on medical leave, had been severed. Out of money, without medical insurance and facing an eviction, the two started the laborious process of moving out. It was slow going. Jacque, who has osteoarthritis, is in a wheelchair. Greg suffered a back injury a year and a half ago and has been on medical leave ever since.

In mid-June, after nearly three weeks spent moving their household into storage, the two found themselves with no place to go. Family wasn't forthcoming with help, Jacque says, and as for friends, well, "My husband's a very proud man," she explains briefly, and leaves it at that.

A shelter was out of the question--"Not with my bird and my cat"--and so the Amdals loaded up their Ford Econoline 150 conversion van (on which Jacque's still making $200 payments) and went camping.

Camping isn't easy for people in wheelchairs, as Jacque has learned. At Grant, where the campground lies on a hill, even the handicapped space is too steep to negotiate in a wheelchair. She's dependent on Greg for everything, even trips to the bathroom.

They've been here a week when I meet Jacque. She's a petite, attractive woman with a boyish haircut that's at odds with the dark circles under her eyes. Clean, dressed in tie-dyed overall shorts and wearing a gold cross, she's determinedly chipper. Her campsite is immaculate and well-appointed. Candlesticks grace the picnic table and a trunk in the large tent which serves as a coffee table. The Coleman stove, grill and lantern are all shiny and new, and an assortment of bright mesh bags for silverware, dishes and dirty clothes hangs from the park-furnished food safes. I comment that she's well prepared for this.

"You know, I've always been a camper and I enjoy camping. If this weren't a have-to, it would be enjoyable."

Inside the van, a fluffy 14-year-old cat lives with a caged cockatiel.

The Amdals are on the slipperiest of slopes: One wrong move, one more minor catastrophe, and they could slide from their precarious position as "people in transition" to "homeless couple." The peace, privacy and dignity afforded them by the park system helps keep that specter at bay and allows them to believe their situation is temporary, and that it isn't hopeless.

Aspiring Slum Lord

IT WOULD BE BAD FOR BUSINESS, in a county like Santa Cruz, where tourism is the leading industry, to advertise that the family in the next campsite might be wondering how they're going to stretch two packages of hot dogs into next week. Nor would it pay to publicize that park rangers are stalking around sniffing out people in unfortunate circumstances.

Here in Santa Cruz County, the Parks and Recreation department's reluctance to address the reality of homeless campers reflects our culture's deep ambivalence about unsightly or unfortunate people: No one really wants to look at them, but no one wants to be the curmudgeon who kicks them out of the way, either.

My ex-boyfriend jokes that Santa Cruz should just post a sign that says "Closed."

When we moved here almost two years ago, we knew no one in town. We had no jobs, and since UCSC's fall quarter had just begun, housing was next to impossible to find. It didn't matter, anyway--we first needed jobs in order to get a house.

So we used the Cupertino address of a friend, signed up with an answering service accessible to us by pay phone, and car camped while we looked for jobs and sent out resumes typed up at a Mailboxes Etc. on a rented computer.

Try dressing for an interview in the woods. We were rumpled, tired and sick of driving. I landed a job in a coffeehouse after a couple of weeks, and a week or two after that we rented a room from an aspiring slum lord.

A month isn't long to camp out. Families do it for fun all the time. We became experts at pitching our tent in the dark. We could break camp and be out of Henry Cowell or Mt. Madonna in minutes. At first we joked about hanging our diplomas on the tent walls. We joked about being the Beverly Hillbillies.

About a week and a half into it we stopped joking. The camping life is hard if it's not truly a vacation. Tiresome as it became, there's no doubt in my mind that we would have left California had it not been for the park system. And who knows? Maybe we should have. California already had too many people when we showed up.

The idea of camping out still shimmered with adventure even after the reality of it had begun to rust. We knew that later we would reminisce about our camping days, mentally filter out the dirt in the tent and the cold nights and the scared feeling we started getting as the weeks rolled by, and determine that we'd been plucky. Staying in a shelter, on the other hand, would have felt like disaster from beginning to end, and we would not have put the photos from that time in an album.

Before I fell asleep each night I imagined how my house, when I finally found one, would look. It would have plants, a bathtub lined with bottles of bubble bath, a shelf for tea. I coveted drawers and closets and lusted after a porch to sweep.

It's been said that most people--even those on suburban streets with Toyotas out front and VCRs in the living room--are just a few paychecks away from homelessness, just two or three bad months away from lying in bed shivering and fantasizing about rolling out of a warm bed and showering in their own bathrooms. Just a season's time away from dreaming, as I did each night before falling asleep, as Marie does when she straightens her sleeping-bag bed so that it's perfectly centered in her impeccably clean tent, of a place to unpack their bags and call home.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Look Homeward: Greg and Jacque Amdal lost their duplex when Greg's disability benefits were severed. The couple has been living in parks, including Mt. Madonna, ever since, but long for a real home.

Robert Scheer

From the July 23-30, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.