![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Oral World's Return

From the Catskills to the Monterey Bay area, storytelling is enjoying a renaissance, thanks to the tales of Donald Davis

By Traci Hukill

JONESBORO, TENN., is a gingham-lined, potpourri-scented pocket of nostalgia tucked deep in the Appalachian hills. Locals, tourists and history buffs know it as the Volunteer State's oldest settlement, but what Jonesboro is famous for nowadays isn't its wealth of hand-stitched quilts or its cozy, cluttered antique stores but the National Storytelling Festival, an annual autumn extravaganza that swells tiny Jonesboro's population by thousands and is ground zero for a nationwide effort to revitalize the art of storytelling.

Of course, most storytellers will tell you, storytelling never really died out. People have bragged, moralized, exaggerated and embellished since the first mastodon hunt. They always will. Parents still tell children bedtime stories, and gossip, which is the real national pastime, is probably storytelling's liveliest ambassador. Spinning yarns, in fact, seems as natural as eating, foraging for intoxicants and falling in love--it's just part of human nature.

"All of us are storytellers instinctively," insists Erica Lann-Clark, a Santa Cruzbased storyteller who specializes in ethnic folk tales. "We come by it because we all speak. We come out of the womb telling our first tale: 'WAAAH!' And that story gets us lots of pretty good attention."

But storytelling as a community activity, as proof of common heritage, has suffered some devastating blows at the hands of technology. Gutenberg's printing press seduced the Western world away from the oral tradition, offering up literacy as the most desirable way to communicate. It immediately proved a divisive trend. Storytelling became the entertainment of poor illiterate folk, while wealthy, educated people sat reading in well-appointed ivory towers.

Eventually, literacy trickled down the socio-economic pyramid, but its democratization didn't make it a substitute for the oral tradition. The trouble was, as Lann-Clark points out, that literacy interiorizes both reader and writer. As intimate as literature can be, it is a medium one step removed from the creator. Reading Maya Angelou is good--really good--but seeing her eyes twinkle slyly as she tells a naughty poem and listening to the rustle of her bright red dress as she strides around stage making grand gestures is great.

When radio came along in the early part of this century, it made listeners of us again--but passive listeners. The human element was still too far removed to satisfy the need for close personal contact. Television didn't do the trick, either, although it fooled a lot of people into thinking it made a great babysitter or drinking buddy. Computers, the Internet and email all further isolated us to the point where people in the same office now choose to type messages to each other rather than speak them.

Crazy for Closeness

ALL OF WHICH LEAVES us in a much- discussed but little-addressed crisis in communication. Recently a Cupertino radio announcer observed that Japan is raising a generation of nerds--children who are extremely computer literate but whose social skills have atrophied from years of neglect. They can't talk to each other because no one talks to them. And this is where storytelling comes in.

"People respond to a real interaction with a living human person," drawls North Carolinan Donald Davis, a retired minister and nationally known storyteller who will be appearing at the Capitola Theater on July 23. "The big deal with the Internet is it's trying to do that, but it can't. TV doesn't totally do it because it's one-sided. The Internet is two-sided, but the trouble is there's not a real person there. With storytelling you're meeting a real human who has to respond to a real audience."

Lann-Clark is more succinct: "The computer and the TV are making us crazy for closeness."

All good stories have a few elements in common: interesting characters, a strong sense of place and a point. Told stories, says Jay O'Callahan, a storyteller from Boston and one of the country's finest, are a lot like written ones. "It's just like writing, only you're writing in the wind," he muses.

For O'Callahan, characterization is the key to storytelling. He tells original, fanciful tales with an actor's flair for expressive dialogue that brings Robin Williams to mind. "The commitment to characters has to be total," he says emphatically. "Each character must have its moment to come alive, and it has to come not just from mimicry but from down low. As the storyteller, your body is kind of loaned out."

Part of storytelling's spell lies in the immediacy of audience response. O'Callahan knows his magic is working when his listeners laugh or get very quiet. "If it's working, the silence kind of gets deeper. It gets velvet and black. That sense of everyone being together, being concerned with these characters, is one of the nicest things that can happen to me as a performer."

To Donald Davis, good stories, like God, are in the details. Details bring stories to life, details make people laugh. And laughter, he's learned after years of preaching to dozing congregations, is the gateway to real communication.

"There's no compassion without humor," he says. "That's a mistake people make--thinking they can be serious without being humorous. Humor enables us to feel. It's the doorway to really being serious.

"But it's not about jokes," he warns. "Nobody remembers jokes because they're not about real people. When we laugh, most of the time we're saying, 'I see it.' Most humor comes from the descriptive parts, not the plot parts. Every time people laugh, that tells me they just saw a picture."

Learning Something Old

RUTH STOTTER DIRECTS the storytelling program at San Rafael's Dominican College. She explains the difference between a storyteller and a stand-up comic this way: "With storytellers you get double your money," she explains. "You get to know them. You have an idea about whether you could ask them for money or invite them into your living room." Donald Davis, she says, is one of the most beloved storytellers around, and one of the few who actually grew up hearing stories.

Raised in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, Davis absorbed the Appalachian tradition of storytelling as a boy. When he went away to Davidson College, though, he left all that behind. In "Stanley the Easter Bunny," a story scheduled for release on cassette this fall, a young Davis, eager to fit in with his citified peers, sheds his ties to home along with his country clothes.

"I got t' Davidson College," Davis declares, "and the day I got there, I became a liar. I mean, I got there wearing blue jeans and plaid flannel shirts and before the day was over, all that stuff had gone in a Salvation Army box, and I had cleaned out mah daddy's bank account buying pleated trousers, Gant shirts, Bass Weejuns so I could fit in. And I lied about where I'd come from. 'Sulphur Springs, North Carolina? I've never heard of that. I'm from--" his words slow to a carefully enunciated crawl-- "close to Asheville.'"

One bachelor's degree and one master of divinity diploma later, Davis had nearly succeeded in forgetting how to tell the stories he'd learned before college. More correctly, they'd nearly been schooled out of him. He reconnected with the old habit in an effort to get his congregation's attention. "Once I recovered from what I learned in school," he recalls, "and let the oral world I'd grown up with into my sermons, people woke up. And it wasn't learning something new, it was learning something old."

What began as a tool to enrich his work as a minister eventually evolved into an independent career. Twenty-three years after finding his first congregation, Davis decided to become a full-time storyteller. He's been doing it for more than 10 years now, has made more than 30 storytelling recordings, published eight books and travels about 300 days a year performing as a storyteller and leading workshops.

It's a pretty nice way to make a living, he chuckles. "I used to think, 'I'm cheating! This is easy!' But then I'd think, 'No, I'm not cheating. I've been preparing for this all my life.' "

This year will mark the National Storytelling Festival's 25th anniversary. And no doubt among the thousands who gather in Jonesboro to listen to Davis and other storytellers there will be a few who think, "I've been waiting to hear this all my life."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

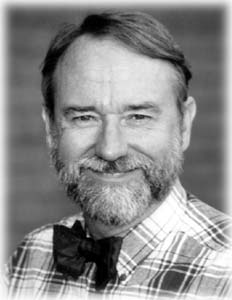

Bow and Constrictor: Renowned storyteller and retired minister Donald Davis leaves his Appalachian home to tie one on at the Capitola Theater on Wednesday for a night of nuanced storytelling.

Donald Davis will tell stories from Appalachia at the Capitola Theater on Wednesday, July 23, at 7pm. Tickets cost $6 for adults and $3 for kids. Reservations are recommended. Davis is also leading a storytelling workshop that day at Seeds of Change Children's Bookstore in Capitola. For more info on the workshop or the show, call 464-1601.

From the July 17-23, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.