![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The Toxic Hit Man

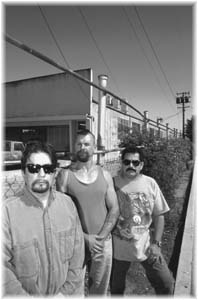

Photo by Robert Scheer

Many people knew that Alton Tobey's Westside plant was a health hazard, a dangerous workplace and a toxic mess--but it took county health officials almost 20 years to clean it up

By Kelly Luker

PERCHED BACK BETWEEN Safeway and Ferrell's Donuts on Mission Street, the industrial buildings and old shacks of Tobey's Rasp Service would catch few people's attention on their way out toward the stunning views of Highway 1. But there behind a chain link fence, a scene reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch has been unfolding for at least two decades.

Records show that Tobey's was a toxic industrial nightmare. Employees here toiled over a toxic stew of cyanide-laced chemicals, fishing out parts with their bare hands. Protective clothing, when it was provided, consisted of paper dust masks, mechanics' coats and rubber gloves with gaping holes carelessly patched with tape. A "cyanide room" offered only a broken window for ventilation from the deadly fumes.

Hundreds of rusting barrels filled with toxic sludge sat unmarked. Hazardous waste was hidden, shipped out illegally to landfills, dumped down sewer drains or simply poured out on the grounds surrounding the property.

Remarkably, little of this was a secret to those paid to protect the environment.

Beginning in 1980, TRS and its owner, Alton Tobey, were repeatedly cited by city, county and state officials for serious environmental violations--including improper use, storage and disposal of deadly chemicals. But no court case was ever brought against Tobey's until last year, when the Santa Cruz District Attorney finally won one of the largest civil penalties in the county's history.

Two ex-employees of TRS claim that repeated exposure to toxic compounds destroyed their health. And the grieving daughter of another former Tobey's worker says that the illegal work conditions killed her father.

Besides their anger, Marcus Banuelos, Frank Medina and Sandy White share one question: What took the District Attorney so long to put a stop to this foul business?

Public documents on Tobey's Rasp Service are voluminous, filling three bulging files in the county's Environmental Health Department. They are necessary in telling the story, because Alton Tobey is now dead, and the relatives familiar with this family business will not comment. Tobey's attorney, Nick Drobac, did not return several phone calls.

Although county officials and former employees paint a vivid picture, it is left to the documents to partially answer the question that troubles Banuelos, Medina and White.

By all accounts, Alton Tobey was a brilliant man and an accomplished inventor. Tobey's Rasp Service grew out of one of his most successful inventions, a rasping tool used in the tire retreading process. Creating an abrasive surface for this tool required a variety of toxic chemicals, including sodium cyanide, tungsten carbide, tetrachloroethylene and copper paste, as well as known carcinogens such as nickel and lead. Nevertheless, the risk factor from these toxins could be kept within reasonable limits in a carefully controlled work environment.

Tobey's Rasp Service was anything but.

Death and Tires

'TOBEY'S COMPANY KILLED my father," says Sandy White, her voice trembling. "There's no other way around it." White remembers her father's constant headaches, dizziness and chronic upper respiratory infections. After 15 years with the company, Leland White had lost his sense of smell. He was 67 years old when he died four months ago of squamous nasal cell cancer, a rare and extremely aggressive form of cancer which three different doctors attest is chemically induced.

Lacking marketable skills, White did not consider looking elsewhere--he worked at TRS for 30 years--or complaining to Alton Tobey.

"My father was the type of man who made no waves whatsoever," remembers Sandy. "It's just the way he was."

Not that complaining would have done much good. Marcus Banuelos, who worked at TRS for five years in the mid '80s and returned for six months in 1995, remembers that workers who voiced concerns about safety were threatened with firing.

Banuelos recalls mixing chemicals and bringing them to a boil in the closed metal shed: "I'd run out to gulp air when Tobey wasn't looking," he says. "You'd have to feel the [metal parts submerged in the cyanide mixture] with your bare hands to check to see if the stuff was ready to fall off."

Banuelos says he still gets headaches. Muscle spasms jar him awake at night. His memory and concentration are shot.

Like Banuelos, Frank Medina also gets uncontrollable spasms and sees his memory and concentration worsening. He also has difficulty breathing.

"I just feel uncomfortable in my skin," he says.

Medina worked for Tobey from 1984 to '86, then again from 1992 until '95. He substantiated Banuelos' testimony to D.A. investigators that Tobey would have employees hide hazardous waste in dumpsters, stash it at the bottom of barrels, ship it offsite in unmarked trucks, pour it along the fence line or flush it down the sewer.

Steve Schneider of the county's Hazardous Materials Program says that about half of Medina's and Banuelos' claims have already been substantiated through soil samplings and further evidence.

Another former employee, Mark Cummings, echoes Banuelos' and Medina's memory of their experiences there--and says that the mishandling of chemicals was part of a deeper insensitivity.

Cummings recalls that Tobey called Banuelos the "dumb Mexican" and Medina the "short Mexican." Leland White, Cummings says, was often told he was stupid.

Given Tobey's alleged cruelty, the dangerous situation, the poor pay (after 30 years, Leland White was making $9 an hour) and the unethical if not downright illegal nature of their work, why did these workers all stay so long?

Desperation, they say. Both Medina and Banuelos say they had drug problems and, like most of the workers there, no marketable skills. Cummings says he stayed for the profit-sharing plan. Medina admits the question haunts him today.

"I didn't think of the consequences at the time," he says. "I saw it as a job, and it paid the bills."

They also all hint at something more troubling. His former employees say they might know why Alton Tobey didn't go to court for 16 years. "He used to say, 'If you have money, you can get away with anything,'" Medina says.

All three employees say they always knew when an inspection was planned, even though inspections are supposedly unannounced.

Schneider admits that somehow the business always did seem to know when inspectors were on their way. But he emphatically denies any allegations of bribery.

"That's absolute nonsense," Schneider flatly states. "It doesn't happen. I know these [inspectors] and they're dedicated to what they're doing."

Fine and Dandy

ALTON TOBEY AND HIS company first came to the attention of the county's environmental health division in May of 1980, after UCSC's campus newspaper, City on a Hill Press, published an exposé on the business and its blatant violations. A county inspection quickly followed and officials discovered more than 100 unmarked drums of toxic waste, as well as contaminated soil around the property where poisons were dumped. Tobey was cited and told to file a written plan of correction. No fines were levied.

In 1985, an inspection by the state Department of Health Services (DHS) again found violations so serious that it requested that the District Attorney file charges. The DA did not, and Tobey was found to be in violation again upon the next month's inspection--as well as the following inspection six months later.

Still no charges were filed and no fines were levied.

Tobey was cited again for noncompliance in 1988, then again in 1989. In 1990, he was still being asked by DHS to take corrective action. In 1994, his own daughter, Barbara Childs, phoned in a complaint on Alton Tobey about his illegal use of cyanide. Still no fines.

It wasn't until an inspection in October of 1995, when officials discovered a shed filled with unlabeled toxic waste, that legal action finally began.

"This is a nightmare," says the county's Steve Schneider. Asked how bad TRS was in terms of environmental violations, he responds, "It was one of the worst."

Schneider notes that each time Tobey was directed to clean up his act, he seemed anxious to comply. "Tobey said he'd do anything to get in compliance," Schneider recalls.

That, he says, is one reason no legal action was taken. Another reason, he says, was that many of the environmental laws affecting businesses are still relatively young.

"Most of these laws weren't on the books yet [1980]," Schneider notes. The laws that were in effect by 1985 were confusing--as they are today--and still poorly understood by many business owners, he says.

"We try to give people the benefit of the doubt," Schneider says. "Our primary goal is to educate businesses on how to comply with complex environmental laws which change all the time."

But officials were also tricked. Schneider says that inspectors would arrive, but were asked to come back another day or were detained in the front office for a cup of coffee while workers out back furiously covered up and locked away the most blatant problems.

Inspectors were told that barrels were full of metal parts, when the parts were merely sprinkled on the top to cover up drums full of toxins. Or inspectors were told that nothing was in the sheds, so they didn't bother to look.

"There was deception," Schneider says. But given Tobey's spotty compliance history, why would inspectors allow themselves to be dissuaded--either told to come back or guided away from certain areas?

"We're not used to things not working," says Schneider. "And we didn't have any real proof."

Easy on the Old Guy

IT WASN'T UNTIL WORD of the 1995 inspection leaked out that former employees came forward and directed officials what to look for, as well as where to look. "And," adds Schneider, "think of it from our perspective: Why would someone save this stuff?"

But Schneider admits that government didn't do enough to protect TRS's workers or the community. "We do share some responsibility," Schneider says. "We got too complacent."

Don Gartner was the district attorney who began legal proceedings against Alton Tobey in 1985, then stopped. Asked why he decided not to file charges, Gartner says that his office was assured by Health Services that the property had been cleaned up.

Alton Tobey's son, Robert, was vice president of the company. Grandson Mike Viviane and former son-in-law Ed Viviane held crucial positions. Other assorted relatives worked at various times and in various jobs at TRS. Bob Yoder, related to Alton Tobey by marriage, is now in charge of TRS.

Yet although public documents indicate that family members knew the nature of Tobey's criminal activities, none within the company ever blew the whistle. "Employees and family members were constantly threatened with their livelihood," Schneider explains.

Steve Baiocchi, the environmental health inspector who made the 1995 discovery that led to the civil case, had not covered that beat for several years. He was told, as were previous inspectors, that no one could get into the infamous shed.

However, Baiocchi says, he demanded that Tobey open the shed, then found the barrels full of toxic waste. The company site was sealed off, and the hazardous materials team was brought in to assess the situation.

Even after all the problems at TRS, Schneider says he was shocked.

"For us to find Tobey's was an eye-opener," Schneider says. "We didn't expect it. But after that, every one of my inspectors started thinking and looking differently [at businesses]. We're going to be more vigilant than we were."

Alton Tobey died last month at the age of 85, but his legacy is far from over.

Medina, Banuelos and White have begun litigation against the company they say robbed them of their health and, in Sandy's case, her father.

While hazardous materials clean-up continues at the company under the watchful eyes of governmental officials, Tobey's Rasp Service is still in business, still shipping out rasps throughout the nation.

And somewhere--maybe in the ocean, maybe in your drinking water, maybe in some abandoned field where your kids play--chances are that some of Alton Tobey's toxic sludge has found a final resting place.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Fumed: Former Tobey's Rasp Service employees Frank Medina (left) and Marcus Banuelos (right) say they were poisoned as the result of unsafe conditions at the Mission Street business. Co-worker Mark Cummings (middle) says his ex-boss, Alton Tobey, who passed away last month, was both mean and sloppy.

From the July 17-23, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.