Can We Talk?

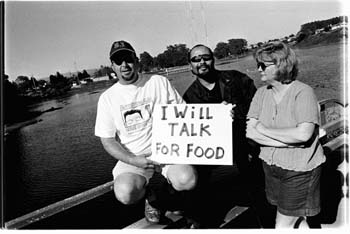

Sign Language: Former talk-show hosts and salesperson (from left to right) Noel Murphy, Rob Roberts and Helen Meline say that KSCO's owners exploit and abuse their workers.

Former talk-show hosts of KSCO say that the local radio station's policy of unpaid labor is illegal and exploitive. Kay and Michael Zwerling say that workers should be grateful for the opportunities they have been given.

By Kelly Luker

WITH HIS MORNING-drive show dubbed "Fred for your head," KSCO-1080AM radio personality Fred Reiss built an audience by cracking jokes, skewering local politicos and generally tickling funny bones.

Yet despite appreciative listeners and a glowing profile in one of the local entertainment papers, last year Reiss was told by station owners Michael Zwerling and his mother, Kay Zwerling, to take a 50 pecent pay cut. When he refused, says Reiss, he was fired--two weeks before Christmas.

Reiss' story is unusual in two aspects: He was one of only two hosts in the history of KSCO to actually receive a wage for his services, and he is one of the few to fight back by filing a complaint with the California State Labor Commission about unfair labor practices.

Although Reiss stands alone in some respects, he has plenty of company when it comes to miserable memories of working for the Zwerlings. More than a dozen former KSCO on-air personalities and salespeople have come forward, branding the station's owners exploitive and abusive employers who routinely flaunt labor laws.

Meanwhile, the Zwerlings insist they have done nothing wrong. In fact, they argue, people who want to be on the air should be grateful for the privilege.

The controversy illuminates a debate not unusual in a town like Santa Cruz. With a huge pool of creative people and few avenues of expression, is the situation at KSCO exploitation or opportunity?

Reiss' Pieces

FRED REISS was hired by Michael and Kay Zwerling in the summer of 1996 to host the afternoon drive-time show. His agreement was virtually the same as for all talk-show hosts: He would be an "independent contractor" and receive no cash for his services. Instead, he would be given air time each hour to sell for advertising--a practice known as selling "avails." It is a practice that general manager Michael Olson says may be used elsewhere, but he admits he has not encountered it at any of the other four radio stations where he has been employed in his career.

Reiss' ratings were so impressive that Michael Zwerling wanted to switch him to morning drive-time, which Reiss refused to do without pay. So the Zwerlings agreed.

Opinions differ on exactly why things went south beween Reiss and the Zwerlings. The talk-show host says that the owners broke a two-year contract by trying to get Reiss to take a 50 percent pay cut less than a year after he began. Michael Zwerling does not dispute he tried to break the contract but claims that the station could not afford to continue paying Reiss at that rate. Reiss' response, say the Zwerlings, was to attack them on his show.

"We had to let Freddy go after he badmouthed us on the radio," says Kay. "He was difficult and whiney."

Mike Mason, a staunch Reiss supporter and former fill-in host at KSCO, admits that is true. "He absolutely savaged a mythical business owner," says Mason. "He didn't mention any names, but everyone knew who he was talking about."

Regardless of how the relationship was defined or ended, the State Divison of Labor Standards Enforcement will be more interested in how that tricky term "independent contractor" actually worked in practice.

According to the California Labor Code, "the most important [determining] factor" in defining an independent contractor "is the right to control the manner and means" of delivering the work.

It's a relationship that works well between homeowners and housepainters, or publications and freelance writers. Payment may be by the hour, by the word or by commission, but the key is that independent contractors pay their own taxes and benefits. As a result, some employers are tempted to stretch the definition of independent contractor and avoid the headache and expense of hiring. For those reasons, the labor commission and the IRS look closely at such relationships.

"[The Zwerlings] say you're an independent contractor," explains Reiss. "But if you are, why do you have to follow station policy?" Reiss says he was told that there were certain performers he couldn't interview, or businesses in town he could not mention because that would constitute free advertising. His contract also prohibited him from working at any other radio stations during his tenure.

"Based on those facts--being prohibited from working at other radio stations--shows there is direction and control over their work," says State Labor Commissioner Jose Millan, when asked about the legality of such an arrangement. "There's a presumption in every case that there is an employer/employee relationship. The burden is on the party claiming that there's an independent contractor relationship."

If the Labor Commission finds in Reiss' favor--a hearing for Reiss and KSCO is scheduled for July 29--it will not be the first time the Zwerlings have misused the independent contractor status.

Helen Meline worked for four months in 1997 as an ad salesperson at KSCO. She says she left when Michael Zwerling tried to get her, as he did with Reiss, to take less money when he pressured her to sign a letter agreeing to no longer take commissions on station commercials that she had been servicing. Contesting the independent status, she filed for unemployment with the Employment Development Department, which found in her favor when it determined that she was an employee.

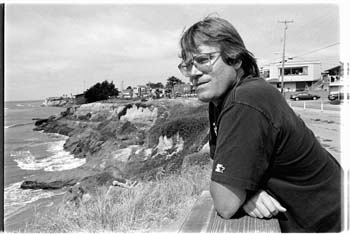

Cliffhanger: Fred Reiss has filed a complaint with the state Labor Commissioner against former employer KSCO to contest his status as independent contractor.

Radio-active

THERE'S SOMETHING charming and offbeat about the little radio station perched on the edge of Corcoran lagoon east of town. The bizarre inside stories and juicy gossip dished by former employees add an air of resemblance between KSCO and that popular '80s sitcom about another radio station owned by a middle-aged man and his mother, WKRP in Cincinnati.

Purchased for $600,000 by the Zwerling family in 1991, KSCO had already been broadcasting to the Central Coast for more than 40 years. It has been the first--sometimes only--news source to tune into during the region's history of natural disasters.

KSCO tried to offer a breath of fresh air by turning much of its airtime over to local folks. Although some hosts were the auditory equivalent of a train wreck-- too awful to witness, too awful to turn away--Michael Zwerling also had a gift for finding talent--and the outrageous.

Eric Schoeck and "Sleepy" John Sandidge have made their mark in the cultural circles of Santa Cruz. Brian Malone, Rebecca Anderson and John Adams have moved on to other, bigger stages like KGO, Seattle or Internet-related programming. Still others, like Daryl Alan Gault and Rob Roberts, had a talent for inflaming listeners with their right-wing rhetoric. Although deeply divided by politics and personal styles, many former employees have found unity in their struggle with the Zwerlings.

Now head of the entertainment booking agency Snazzy Productions, John Sandidge worked for KSCO for about six years from April of 1991. Although he was paid when he first got there, Sandidge says, he was also asked to take two pay cuts, then told he wouldn't be paid at all since none of the other talk-show hosts received money. He agreed to work for ad trades but left when he was told which ads he couldn't accept, he says.

"One day I came to work, and there was my picture with crosshairs on it," says Sandidge. The picture was left by evening host Dave Alan, known for his interest in the paranormal and conspiracy theories. "[Michael] Zwerling said it was a joke. What other workplace could you do that and not get reprimanded?"

John Adams, now a program director for Imagine Radio, worked at KSCO from 1994 to mid-1996."Everyone there is verbally abused," he recalls. "Kay would call me in the middle of my show and yell at me. She would call to express her disapproval of different segments." As Adams speaks, he admits he was embarrassed that he stayed there so long taking the abuse--and for no pay.

"It's weird, in radio you have that environment where people are passionate and committed to the art. But in a market like Santa Cruz, there's not much opportunity for people to get on the air.

"But, if you don't get on the air, you can't move up. So, [the Zwerlings] can take advantage--they can get people to volunteer or to work in what would seem unfair paying practices.

"Yet," Adams admits, "The people who turn on the mike knew what they were getting into."

Lip Service

OPINIONS OF MICHAEL Zwerling from these former employees are mixed, running from pity to bemusement. Kay Zwerling, however, comes in for much deeper criticism.

"This woman makes Leona Helmsley look saintly," says Sandidge.

"Kay Zwerling is the ultimate Dragon Lady," adds conservative Rob Roberts, a popular talk-show host until Michael Zwerling asked him to debate for his job--on the air.

Adds Mason, who once considered himself a lifelong friend of the family: "I used to have a love-hate relationship with that radio station. Now it's a hate-hate relationship."

Mother and son appear stunned that so many former employees have had so little good to say about them or about working for KSCO. They do not dispute the two most common allegations--that they not only don't pay their talk-show hosts, but feel that the hosts should be paying them. The Zwerlings say they provide a valuable service to people who want to break into the business.

"In exchange for allowing them to be on the radio, we'd not only not charge them, we'd compensate them [in avails]," explains Kay.

Most radio is syndicated, Michael Zwerling explains, and the syndicated shows are paid in ad time.

"If we had to pay cash for our programs, there would be no station," he adds.

As far as Michael and Kay are concerned, the detractors are nothing but disgruntled former employees who all brought on their own problems.

"Staff who have been here can be high maintenance," observes Kay. "And Freddy was one of the highest. He has a personal vendetta against us now."

General manager Michael Olson shows a contract signed by Reiss, agreeing to the terms of his leaving. One of those terms is to agree that, as an independent contractor, he would not apply for unemployment.

Reiss admits signing it but says that Michael Zwerling told him he wouldn't give him the money owed him unless Reiss signed it.

Michael does not deny that, but he seems not to care that the contract was of dubious legality, or that asking Reiss to sign it suggested that Zwerling knew his employment practices were questionable.

"Of course I told him I'm not going to give him any money unless he signed," Michael responds. "I wanted to get a release."

Dean Fryer, public information officer for the state Department of Industrial Relations, questions the legality of such a release.

"You cannot hold pay of funds due an employee in requesting this type of waiver," Fryer explains. "[And] you cannot ask an employee to sign a waiver for unemployment insurance."

And, if Michael Zwerling disputes the employee/independent contractor status, Millan adds, "he has the burden of proving it's an independent contractor relationship."

The Zwerlings are asked about some of the popular talk-show hosts they have let go recently. There was Gault, known by his initials, DAG, on the radio.

"At the beginning he was so grateful," remembers Kay. "But as time went on he got [to be] more of a prima donna." He was fired, say the Zwerlings, for allegedly critizing his bosses on the air.

"We were shocked when he talked about us on the radio," says Kay.

There was Roberts, who says that Michael fired him for a sexist slur allegedly made about a female politician. Then Michael changed his mind when Roberts played the show's tape, proving that he did not. However, Michael then commandeered Roberts' time slot, asking the audience to debate whether Roberts should keep his job.

Again, Michael Zwerling admits he went on Roberts' time slot to ask for listener input on Roberts, but says it's because "I got complaints about him."

Asked if he thought that might have been disrespectful and humiliating, Michael Zwerling becomes agitated.

"He's a big boy," storms Zwerling. "He can dish it out, but he can't take it?"

Those who remain at KSCO rally to the Zwerlings' defense. Program director Rosemary Chalmers has worked for KSCO seven and a half years. She says she receives a good wage, use of the company car, health care benefits and a cell phone.

"I have a great package," she says. She also denies allegations by former co-workers that she is often verbally abused by the Zwerlings.

"I'm not the type to stand for verbal abuse," Chalmers says. "I think my longevity here speaks for itself."

The verbose Dave Alan has plenty to say about both his employers and the people who have left. Hosting an evening show as "The Nighthawk," Alan has been with KSCO for six years.

"Zwerling provided an open format," insists Alan. "All these on-air personalities had a generous opportunity to be on a major AM regional market, and they let their egos get in the way.

"They blew it and now feel disgruntled because they're back to being nobodies."

Michael Olson insists there are plenty of employees who have left on good terms, and offers two phone numbers. Julie Lima worked in ad sales for two years until she quit to have a baby.

"I had a lot of fun working there," she says. "It was commission only, but it was a great commission--they were very fair."

Now living in San Clemente, Stephanie Tufts says that the Zwerlings provided her with her first after-college job and valuable experience. Like Lima, Tufts insists the commission structure was generous.

However, the Zwerlings are sadly out of touch with the experience of other former staffers that radio station owners insist left happily. Both Michael and Kay point out that Eric Schoeck left on mutually agreeable terms with the station.

"In fact, we'd love to have him back," smiles Kay.

She shouldn't hold her breath. Schoeck, who had a popular daily show on KSCO for five-and-a-half years, recently left to work as Assemblymember Fred Keeley's district manager. Schoeck says that he is also preparing to file a complaint with the Labor Commissioner about his nonpaid status. Like his peers on both ends of the political spectrum, Schoeck does not leave with happy memories of either Michael or Kay.

"One of the last contact I had with Kay was when she screamed at me," recalls Schoeck of a dispute about mentioning a nonprofit benefit function on the air. "She went off on me and got in my face and screamed at me."

Pork Futures

THE LAST YEAR or so has seen other changes around the Live Oak radio station. In 1997, the Zwerlings bought an unused Watsonville station, KOMY-1340, and moved the bulk of the local programming to that frequency. That left almost 80 percent of the weekday programming on KSCO to be filled with national "feeds," or syndicated shows.

Although it has altered the landscape of KSCO from local voices to Dr. Laura, Dr. Wallach and Rush Limbaugh, Michael Zwerling explains that it makes more sense to use KSCO's 10,000-watt channel for syndicated programs, and KOMY's 1,000-watt channel for local programming.

"It's the best of both worlds," he figures.

Although they now own two radio stations, the Zwerlings have dropped from as many as four salespeople to one--general manager Michael Olson.

"We had a lot of sales staff that couldn't sell," explains Michael. Also, ads may not be as vital to the stations' financial health as they once were. Michael Zwerling has found a profitable tie-in with veterinarian and controversial vitamin pitchman Joel Wallach. Wallach's successful multilevel marketing business for products like his "Pig Arthritis Formula" and "Stud Horse Formula" have been boosted by his talk show, "Dead Doctors Don't Lie," now syndicated by Zwerling to 94 radio stations.

"That's absolutely true," Michael responds. "We don't need salespeople anymore.

"Salespeople," he sighs. "They've been a nightmare. I wish I'd never bought a radio station."

Kay chimes in, looking pointedly at me: "We'd give people a chance, and then they'd turn around and make anonymous tips to newspapers."

However, it's Olson who makes an important distinction about where he works. Olson has been with the company six years and says he is compensated fairly.

"I'm proud to be a part of KSCO," says Olson. "And it's important to remember that KSCO is more than two people--it is about hundreds of staffers, hosts, volunteers and guests who have worked to make this growth possible."

In the final analysis, it will be left to the State Divison of Labor Standards Enforcement to determine who were "staffers" and who were "volunteers."

Adds Millan, "If we have information that this is someone repeatedly violating this law, we would look at criminal provisions."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

From the July 16-22, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)