![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Skate of the Art

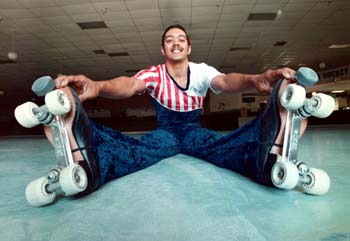

Honor Roll: Roller skater Edrick Stewart epitomizes a world-class balance of strength, precision and artistry.

World-class--and strictly old-school--Edrick Stewart redefines artistic figure skating with his roller revolution

By Mary Spicuzza

THE SONG'S SOFT BEAT breaks into a pulsing rhythm. Edrick Stewart strikes a sharp pose and stands frozen, commanding attention without moving a muscle. Moments later, he explodes into action. He unwinds his long arms and thrusts forward, flexing his lean legs as he effortlessly glides across the rink. With perfect poise and captivating dance moves, the graceful Stewart proves he is world-class before completing a single loop around the floor of the Rink in Scotts Valley.

He'd never admit it, but this teen and other members of the Scotts Valley Artistic Skating Club are leading a revolution in the world of figure skating--an especially remarkable feat considering that there's no ice for miles--Stewart carved out a top-flight skating career without blades of any kind. And he's creating new proof that the days of disco may have come and gone, but old-school roller skating is eternally cool.

As the tempo of his routine's music, borrowed from The Mask of Zorro soundtrack, builds, Stewart weaves across the floor with increasing velocity. He blazes past baby-blue murals lining the rink, all dotted with fluffy silver clouds and colorful hot-air balloons. Balancing on the back of one heel, his other leg held parallel to the ground, he twirls into a red, white and blue Lycra-clad blur. Then he suddenly arches back, leaning into a move that puts his head upside down and spinning remarkably close to the ground. Among insiders in the figure-skating business, the difficult maneuver is known as the inverted camel.

"See that? They don't do that on ice," Jim Pringle, Stewart's coach, says proudly from his raised observation deck.

Stewart breaks from the spin and dances across the floor, sending other skaters rolling toward the edge of the rink. Pink-clad little girls sporting neat blond ponytails stop in mid-chatter, watching with awe as Santa Cruz's world-class skater leaps into the air and completes a flawless triple axle.

For most of the world, figure skating is still synonymous with the cold world on ice and its frigid queens. But at growing numbers of arenas like the Rink, down-to-earth champions like Stewart are staging a creative coup with their emerging sport, known as artistic roller skating.

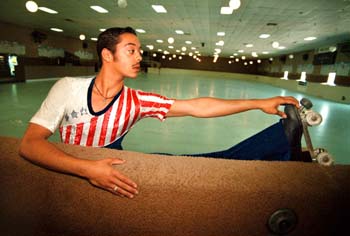

Hot Feet: If Stewart captures the world championship, it could make Scotts Valley an international roller skating mecca.

Skate of the Art

FOLLOWING HIS breathtaking short routine, one of a trio of categories he competed in during last year's world championships in Bogota, Colombia, Stewart glides directly toward the DJ's deck, where coach Pringle and I stand chatting. He flashes a smile at me but fixes his eyes intently on his mentor.

"That last triple sal-chow--you dropped the edge a little," Pringle notes. A "sal-chow" (pronounced sow-cow) consists of a 360-degree turn executed in the air before landing on a single skate. For a triple, the skater must complete a rapid series of three spinning leaps. To my novice eyes, it looked like a 10.

Pringle, an Oakland native, has been coaching skaters--of both the ice and roller variety--for more than 45 years. During his own career, he was a national champion in U.S. Artistic Roller Skating's senior division. "They didn't call it 'world-class' in those days," he says.

Besides making his own accomplishments, Pringle has trained dozens of champions, many at the 9-year-old roller arena tucked behind the Scotts Valley post office on Kings Village Road. "They have different levels of coaches. There's status, junior, elite. I'm an elite," Pringle shrugs humbly. "I guess there are only 25 of us in the whole United States."

Pringle, a member of the prestigious National Coaches Hall of Fame, has also taught for the U.S.A. World Team at the Pan-American Games. After founding numerous rinks, Pringle hopes to build a state-of-the-art arena in Watsonville.

I try to show off insider knowledge by asking about rumors that artistic roller skating will soon be an Olympic event. Pringle patiently explains that artistic roller has been a Class A sport for years and that roller champions have long dreamed of a chance at Olympic gold. But only 20 different nations participated in last fall's world championships in Bogota, not enough to qualify for an event in the games.

Still, it's not exactly a fledgling sport. The U.S.A. Roller Skating website boasts 32,000 members, including speed skaters and roller hockey players, and there are more than 1,000 skating clubs in the country. The bustling Bay Area hosts more than a dozen. And the inclusion of roller speed skating in the 2002 Winter Olympics bodes well for the future of artistic roller athletes.

"Folks are working on it. New roller rinks are opening up all over, all the time," Pringle says, adding, "I teach both ice and roller, and I can tell you we do things on roller that they won't let 'em do on ice."

With a broader base of support, four wheels instead of a single blade and more "edges" to lean on, roller skates allow moves the ice crowd can only imagine. Apparently Pringle is an expert in the physics of roller skating.

"My old coach was very good for me; he taught me to love the sport," Stewart tells me. "But he'd never had a world-class skater before. Jim's been coaching for years, and he's had tons of champions."

After making the switch three years ago, Stewart quickly climbed up the skating ranks--from primary, elementary, freshman, sophomore, and junior to senior. At only 18 years old, Stewart is now pure world-class.

Stretching His Limits: Stewart, a 12-year veteran in his field, has spent most of his young life on wheels.

Speed Demon

STEWART TAKES my hands in his and guides me around a turn. We're working on leading into a forward turn from the scissors, the most basic move for skating backward.

"OK, weight on your right side. Lift your skate, open your hip, now shift to the left and turn." He's more patient with me than most parents struggling to potty train their toddlers.

"And where are you looking now?" he asks suspiciously.

Busted. I'm looking straight down at the glittered toes of my silver skates--a faux pas in roller skating. The sport is all about balance, and that means looking ahead of you, back straight and knees soft. The theory goes something like, Keep your eyes on the ground, and you'll end up falling on it.

With a neat mustache and his black hair sleeked back, Stewart displays a physical presence and emotional maturity unlike thos of any teen I've ever met. He transcends the trendy and is already a man with integrity--Stewart remains devoted to old-school skating, never straying into the inline skating craze. Only his pierced tongue and funky serpent necklace hint at traces of youthful rebellion.

"I'm going to speed you up a little," he says, gently pushing my shoulders as I glide backward.

I ask how he found his calling, secretly hoping to distract him from my jerky scissors. He quickly corrects my posture, then launches into a familiar story of going to a Saturday open skate with his family when he was 6 years old. During the session break, there was a skate club exhibition.

Stewart smiles. "I started lessons the next week."

Watching the polished skater as he wheels gracefully from shag carpeting to the smooth floor, I find it impossible to imagine him stumbling onto a roller rink for the first time. Now he commutes from Marina to Scotts Valley nearly every day of the week, just to skate.

Then there's the public's bias toward the other figure skating, which has long been an Olympic sport and a favorite of traveling Disney shows. Many skaters, like Tara Lipinski, make the switch from roller to ice in search of Olympic gold, fame and fortune.

"I thought about changing to ice, but it was never as convenient for me," Stewart explains. "And it costs twice as much money."

The wealthier sport, which requires renting expensive rink time and personal skating coaches, has launched its Dorothy Hamills and Michelle Kwans to international fame. Meanwhile, the more working-class roller art form too often remains in the shadows. After all, when was the last time an artistic roller skater received big corporate sponsorship or graced a box of Wheaties?

But both Stewart and his craft are now coming of age. The trim, toned teen practices more than 30 hours a week, often for five hours at a time. When Stewart isn't at the rink, where he also works as a DJ during open-skate sessions, chances are he's taking care of his sisters, studying or lifting weights.

"I easily pull 16-hour days. Easily. I skate, baby-sit and live on very little sleep," Stewart laughs. "And I'm not ashamed to say, I love my double nonfat mochas."

Coffee fix aside, Stewart keeps going with a healthy diet and religious vitamin regimen. Not that he need worry about getting pudgy. During intense training before a competition, Stewart sometimes loses up to 15 pounds in one week.

"I've passed out at practice, and sometimes I go into the bathroom and vomit for a half-hour, just out of exhaustion," Stewart says. "But I never stop skating. My little clock just keeps going."

Stewart also takes classes at Monterey Peninsula College and plans to transfer to California State University-Monterey Bay. When asked if friends understand his demanding schedule, Stewart looks at me and laughs. "You act as if I have a life."

Hold the Ice

BRIGHT SUNLIGHT filtering onto the edges of the rink hints at the beautiful summer afternoon outside. But on the floor, skaters are intently focused on their coach.

Pringle stands on the DJ's deck, peering over a donated light from the top of an old police car, and calls out warm-up exercises. He announces "The Blues," and youngsters immediately slow into a soulful stride. A couple pairs off and sways in unison. Both look on with admiration at Stewart and his partner as they glide across the floor.

"His mom isn't very supportive of skating," Stewart later says of a younger male student. "I give him all of my old outfits. And try to be there for him."

A young girl tumbles onto the floor just as Pringle calls for a waltz. Dancing to an instrumental version of "My Favorite Things," Stewart spins his partner, both maintaining professional poise. But nothing is more amazing than watching a couple do the cha cha on wheels.

When I explain that I'm not just a skate groupie but a journalist writing about Stewart, another fan giggles jealously. "Lucky you," she coos. "He's an amazing skater and a great guy. He's wicked. He's too sweet."

"OK, everybody. Denver shuffle," Pringle shouts, interrupting her sighs. "This is Edrick's favorite."

Tensions may rise at the Rink leading up to competitions, but during club practices there don't seem to be any Nancy Kerrigan-Tonya Harding ice-queen rivalries. If anything, Pringle and his students rely on teamwork for their success. The coach spends hours picking his skaters' music, sifting through segments on his old reel-to-reel player. Meanwhile, Stewart inspires and encourages the younger kids, and Pringle's wife and co-coach, Roberta, comes up with all of their champion's tournament costumes.

"She's very good with my outfits. My favorite was last year's. It was all black with a gold dust, covered in rhinestones. So beautiful," Stewart marvels. "They just make me feel so good to skate in them."

As Stewart leaps through the air, wearing royal-blue velvet pants and a white-and-red top covered in rhinestones, he unleashes another competition-winning smile. With the outfit and our photographer's spotlights, he seems made to wear crushed velvet and have four wheels attached to each foot.

But later, donning baggy workout wear as he glides me around the rink, he still looks like a champion. And he breathes a Zen-like understanding of skating. Stewart speaks of staying centered with proper balance, the importance of keeping your eyes focused on a destination and the difference between flexibility and forced movements. But before I'm lost pondering the spiritual wisdom of my wheeled guru, Stewart keeps me grounded in physical realities.

"Oh, and skates don't like to roll sideways," he points out wisely, glancing down at my hot-pink wheels.

Difficult as it is to imagine him without wheels, Stewart says he doesn't always plan to be on skates. He's thinking of a career as a psychologist. But his retirement--which usually comes before a skater hits 30 years old--is the furthest thing from anyone's mind when he takes the floor for his long routine. Again everyone respectfully hurries to the sidelines. Despite his effortless grace, I can't help wringing my hands with every leap. He's just someone who deserves a perfect 10.

"I've never broken anything, but I've sprained everything imaginable," he reassures me. "But I've hurt myself more off skates than on them."

He explains that most of his injuries have occurred when he was skating too cautiously, making mistakes while trying to be perfect.

"He was a little guy when he first came. But he's grown," Pringle says simply, never one to ooze saccharine-sweet praise.

"He's coming along fine. Senior world-class is tough, but he'll hold his own."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

For information on the Scotts Valley Artistic Skating Club, call the Rink, 251 Kings Village Road, at 438-2222 or 438-2233.

From the July 7-14, 1999 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.