![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Real Goal Getters

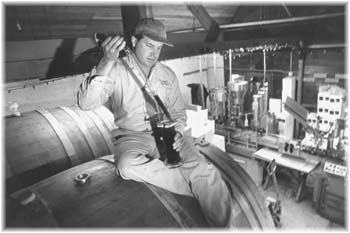

Robert Scheer Riding Those Pipe Dreams: Oenologist John Schumacher extracts a red wine sample with a 'wine thief' for a blend tasting he'll use to determine the proper mixtures for future bottlings of Hallcrest's offspring, Organic Wine Works. Organic wine, beer and spirits producers hope to revolutionize their industries, make a buck andoh, yeah!save the world By Christina Waters THE GROWTH CURVE of organically produced wines, beers and spirits is soaring visibly if gently skyward, thanks to increasing numbers of eco-entrepreneurs mining the appetite for natural libations. Still occupying a slender outpost of the national alcoholic beverage empire, the growth in organic-specialty beverages reflects interest in sustainable-production practices, especially in the West. In Felton, UC-Davis-trained oenologist John Schumacher has gradually expanded his Hallcrest winemaking operation to embrace a second label, Organic Wine Works. But in Schumacher's case the "organic" designation doesn't simply apply to agriculture--it permeates every inch of the winemaking process, from chemical-free growing conditions to additive-free fermentation. "We were determined to serve customers who were sensitive to sulfite additives," says Schumacher, whose chardonnay was the first organic, sulfite-free wine of its kind to be released in the U.S. Though all wines contain naturally occurring sulfites in minuscule amounts, those containing more than 10 parts per million must be labeled with the "contains sulfites" warning. Schumacher believes that the consumer for his additive-free wines is more concerned about the sulfite issue than about the organic factor. "There's not much added value to an organically grown grape," Schumacher says, "just because in California there's such a lack of product." But once they do try the sulfite-free wines, Organic Wine Works customers tend to be loyal, says the winemaker/owner. With his product on the shelves of most natural foods stores in 30 states, Schumacher believes that all things being equal, organically grown grapes are desirable. However, he notes gloomily, "Grape-cost instability is incredible. I'd like to keep the prices down--people should be able to afford wine every night. But the competition from Europeans, Australians and South Americans--where grapes are abundant--is intense." "How large is the organic beer business?" Sonoma brewmeister Peter Humes chuckles. "Very small." Aside from a handful of artesanel groups in Europe and a few experimental false starts here and there on the American beer map, Humes may well be the sole creator of bottle-conditioned microbrew beer made entirely from organic ingredients. His Humes Brewing Company quartet of ales and stouts appeals to those interested in natural cultivation of hops, barley and malt, as well as to finicky connoisseurs.

What's the problem with sulfates? And just what does organic really mean?

Real Growth Industry A TRIP TO CALIFORNIA almost 10 years ago convinced Humes he was in the midst of an organic revolution. " 'Why wasn't anybody making organic beer?' I wondered. Having been a chef for a long time, I had loved organic foods, so I just started in on beer," he says. Unlike pasteurized beer, whose foamy head is the product of injected carbonation, Humes' non-pasteurized beers continue to age in the bottle, thanks to a dose of fresh brew added just before bottling. Filtered, gravity-fed spring water forms the backbone of Humes' beer, which gets its flavor via organically grown grains from Canada and Scotland. Hops for Humes' 600-plus barrels of annual output are imported from organic growers in New Zealand, Tasmania and Germany. Once their work is done, spent grains and hops are composted back into the landscape surrounding the small Sonoma brewery. Humes' handmade beers have found their way to London competitions, upscale spirits emporia and natural-foods markets all over the country. Humes entered the California market in 1993 at Whole Foods stores in Berkeley and Mill Valley, quickly adding more natural-foods purveyors as word got around. "I go to the Great American Beer Festival each year in Denver, and distributors get to know me that way," Humes explains. Given the labor-intensive style of production and the brewery's small size, Humes admits his product is aimed at the high-income, educated consumer, rather than exclusively at the natural-foods customer. One look at a freshly poured glass of unfiltered Cavedale Ale--the full glory of whose thick, creamy head takes long minutes to form--and then a taste of this golden brew, lends credibility to its upscale price tag. "It's definitely a niche market," he says. Footsteps of the Giant IN BEER, MAYBE, BUT ORGANIC winemaking is attracting the attention of even large-scale operations. Up in Mendocino, Fetzer Winery--at 3 million cases annually one of the giants of California winemaking--added a new proprietary label, Bonterra, in 1992. Dedicated to producing premium wines made exclusively from 100 percent organically grown grapes, Bonterra has expanded in five years to 120,000 cases annual output, with no end in sight. "We saw the label as a great opportunity for a product marketed exclusively as made from certified organic grapes," says Fetzer director of public relations George Rose. What that means is that these wines are made from either certified vineyards in which no pesticides, herbicides or synthetic fertilizers have been used, or are grown on Fetzer's own certified organic vineyards--at 360 acres, Fetzer is the largest organic grape grower in the country. While the wines themselves aren't considered "organic"--to bear that label, as do Hallcrest's Organic Wine Works products, the wines themselves would need to be fermented without added sulfites--the California Certified Organic Farmerapproved growing conditions for Fetzer grapes give the Bonterra label a value-added cachet. "It makes a statement about our farming practices," Rose says, pointing out the Fetzer company philosophy to encourage all its vineyard growers to follow sustainable techniques. Fetzer has long been an eco-industry pioneer, vitalizing its agricultural base through extensive composting, use of cover cropping and experimenting with sound environmental practices on its showcase Bonterra Garden. Very low levels of sulfites are used during fermentation and aging of Bonterra wines in order to ensure shelf stability and prevent oxidation, and to ensure preferred aging of the wines. "The wine is marketed in the conventional sense--we haven't made a major push to market it to the natural-foods segment yet," Rose notes. "It's been an education process, but now it's time to go after the natural-foods clients." To hand-sell the wines and expand Bonterra's growth potential, Rose says, the demonstration process is key. "We'll be showing the product in the Fresh Ideas tent at the Natural Foods Expo," he says. "And we've been invited to various national and regional eco-tastings." Eye-catching shelf talkers and strategically placed back cards highlighting Bonterra's ecologically correct pedigree already are part of the marketing program for natural-food market shelves. Meanwhile, conventional distribution continues to work well for the oak-aged varietals created by Bonterra winemaker Robert Blue. Spiritual Calling ALL THE ACTION on the organic elixir front isn't centered on the West Coast. A distillery in Kentucky is currently busy turning out the national tipple of Russia from organically grown American grain. RAIN vodka is a new micro-distilled vodka made at the Leestown Company distillery in Frankfort, Ky., legendary for its fine sipping bourbons. Given the interest in sustainable agriculture, it was only a matter of time before grain grown free of pesticides would be used in making fine spirits. RAIN begins with Kentucky limestone water and ends with four distillations and diamond-dust filtration. The vodka turns out as pure as rainwater--hence the marketing hook. RAIN vodka is something of a departure for its parent company, Sazerac, better known as the corporate giant purveying an array of spirits like Ancient Age bourbon, Speyside Blended Scotch and Herradura tequila. To reinforce its new interest in sustainable production--RAIN is packaged in recyclable containers made from recycled paper--Sazerac recently became a sponsor of The Wilderness Society. In September 1996, RAIN vodka premiered with 17,000 cases to test the waters of consumer interest. Sazerac Director of Public Relations Rudy Moeller admits that "the fact that there are quite a lot of worthy competitors out there" is the organic vodka's biggest challenge. "So far the organic angle seems to be working for us. Those who've had experience with organically produced grains in other products believe there's more flavor--not unlike a free-range chicken compared with a factory chicken." While not available in natural-food stores, RAIN vodka is distributed in liquor stores all over the U.S., retailing for a competitive $13.99 per 750 ml. "I think the organic ingredients--and we really do use the organic label prominently in all our advertising--makes a statement about how to best use the earth's resources" says the RAIN man. Now that's a sentiment well worth toasting. [ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.