![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

![[MetroActive Dining]](/dining/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Made in the Shade

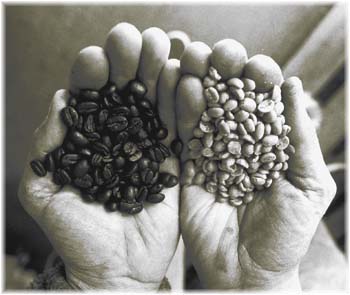

Robert Scheer Bean There, Done That: Outland Java's light raw and roasted coffee beans are shade-grown to produce a full, rich flavor without all the chemicals. Environmental and ethical concerns brew over organic coffee By David Templeton THERE IS A revolution brewing out on the fringes of America's highly lucrative coffee-peddling industry. It is a revolution of ethics and philosophy--spearheaded mainly by the roasters and promoters of organic coffees--and it could end up reshaping the entire industry's economic and agricultural ideologies. It could even change the future of the planet. As is usually the case in such grass-roots industrial revolutions, the decision is solely in the hands--and coffee mugs--of the consumers. And at the moment, the vast majority of this country's faithful caffeine addicts are unaware of this potential turning tide. Most consumers are not acquainted with the ethical issues represented in each and every cup of java that is sipped or swallowed in the kitchens, cars and coffeehouses of this, the largest coffee-consuming nation on the planet. While the lack of chemicals and pesticides is the primary factor that most people associate with organic agriculture, it represents only the tip of the ethical coffee bean mountain. The sustainability revolution that has energized efforts to save the rain forests and educated consumers worldwide also includes those who are striving to give economic stability to the indigenous farmers and laborers in impoverished, coffee-producing countries. Encompassed in the organic ethos are efforts to save these regions' rivers and streams, routinely poisoned by high-yield coffee-processing methods. There are forces working to establish small banks to assist women in coffee-growing villages in launching their own micro-businesses. And--with an eye-opening issue that many insiders believe will finally capture the conscience of the mainstream consumer--there is a growing effort to expose a trend in coffee production that is having a devastating effect on the world's migratory song birds, species that are now rapidly disappearing from our own North American back yards.

Just what does organic really mean?

Respect and Fragility ON TINY Noyo Harbor, in Fort Bragg on Mendocino's windy coastline, Paul Katzeff strides into the bright, aromatic warehouse of Thanksgiving Coffee Company, the iconoclastic coffee-roasting operation he founded with his wife, Joan, in 1972. Specializing in organic coffees, Thanksgiving annually roasts 1.5 million pounds of coffee, all from beans that were purchased from native co-ops and small-scale farmers for 40 to 70 percent above market value, with additional profits (15 cents for each package sold) returned to the growers through nonprofit village banking programs. An outspoken political activist (he once sued President Reagan for implementing the trade embargo on Nicaragua, and marketed a coffee from which a percentage of profit was sent to the Sandinistas), Katzeff has firmly established himself as one of the more dedicated, innovative and aggressive leaders in the coffee industry's ethical revolution. "Look at this," he exclaims, bending down to scoop up a handful of green coffee beans spilled from one of the hundreds of exotically labeled burlap sacks piled all around us and stuffed with coffee from Mexico, Panama, Ecuador, Columbia, Africa, Peru and Hawai'i. "I hate to see beans spilled like this. All of this will be swept up, thoroughly cleaned and reused in one of our blends. If something travels 10,000 miles to get to you, you have to respect it." Respect is a word Katzeff uses often, and it is clearly a vital force behind his business: respect for customers who demand a quality cup of coffee and expect it to be free of toxins and chemicals, respect for the coffee itself--much of which is packaged in bags with a valve that allows the beans to breath--respect for the workers who put the beans in these bags and for the communities in which they live, and respect for the fragile ecosystems in which the coffee plants are nurtured. In recent months, Thanksgiving has introduced a program called Beyond Organic, a system of choosing and promoting coffees that are produced under a strict set of social, environmental and fair trade criteria. Potential coffee growers are rated according to a numerical value chart that gives high marks to coffees that are certified organic, with additional points given when land ownership promotes "strong cultural survival of indigenous peoples," when workers are guaranteed a fair labor wage, and when coffees are shade-grown beneath a natural rain forest canopy. Coffees produced under these conditions are sold in markets with a "Love the Earth" seal. Katzeff's philosophies and practices are further reflected in his company's slogan, "Not just a cup, but a just cup." This concept of coffee justice is being championed by a growing number of organic-coffee companies around the nation. For them, such ethical and humanitarian ideals are a very short stretch from the health-conscious motives that led to them to organics in the first place. Because of their significant collective buying power, these companies already have shown that they can indeed make an impact on the environment--and the way business is conducted. All they need now is an infusion of consumer support. "When Joan and I started this company, I knew that organics was a way to politicize the product," Katzeff says. "We made a stand for what was right. Now, after a lot of work, we've broadened our base. We've found acceptance in the marketplace, and organics is no longer thought of as just a bunch of health nuts afraid of pesticides. "But organics is limited, narrow," he goes on. "There are bigger issues. Humanitarian issues. Right now, 'shade-grown' is the big one. You ask how a coffee company can change the world? I'll tell you--they can support, buy and get the word out about shade-grown coffee." This traditional form of coffee growing requires that coffee be planted beneath a canopy of native trees. Grown in the shade, coffee develops more slowly, creating a higher sugar content that, when the beans are roasted, gives the coffee a richer, fuller flavor. The trees fix nitrogen into the ground, resulting in fertile soil that requires little or no fertilizer or additional help. Pesticides are unnecessary because of the birds that thrive in the shade-giving overstory. Organic coffee, by definition, is almost guaranteed to have been shade-grown. The Fall of the Wild OVER THE LAST TWO decades, this canopy has been torn down as coffee growers convert to a process known as technification. Able to grow coffee three times faster than the traditional method, technification employs a hybrid plant that grows in full sunlight. Valuable to farmers for its profit-producing yield, sun-grown coffee lacks the nitrogen supplied by trees and depends on a steady diet of fertilizers and chemicals. In the absence of a leafy canopy there is consequently an absence of insect-eating birds, thus creating a need for insecticides to protect the ripening coffee bean crop. According to a recent report from the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, this trend toward technification--17 percent of Mexico's coffee crop is now sun-grown, 40 percent in Costa Rica, 69 percent in Columbia--amounts to a devastating loss of habitat for the birds, which have taken to the coffee plantations in past decades due to the deforestation of their original rain forest homes. Of the 150 different species of birds that live on shade-grown coffee farms, many are migratory, wintering in southern climes before returning home to North America and Canada. Some of these migrant species are beginning to dwindle in number. Many coffee roasters, in response to these numbers, have begun marketing "bird-friendly coffees," organic blends purchased from shade-grown coffee co-ops. Counter Culture, in Durham, N.C., has introduced a brand called Sanctuary. Thanksgiving recently unveiled Song Bird Shadegrown Coffees, sales from which (15 cents per package) are donated to the American Birding Association. Thanksgiving's Peter Matlin says, "Who wants something that they know will pollute the watersheds and trash the birds? There is an ethical and moral beauty to shade-grown coffees that people will embrace once they understand the issues." "Shade-grown is the hot button," agrees Mark Inman, co-founder, with Chris Martin, of Taylor Maid Coffees, a small organic roaster based in Occidental that buys nothing but shade-grown coffee. "You'll hear a lot about it in the future. Not only is shade-grown good for the birds, it's better for the people. A grower can plant bananas and other fruit crops and earn extra money while providing a canopy for the coffee." Inman, a roaster for 10 years with a mainstream coffee company in Oregon, became disgusted by the profit-hungry business practices he observed. With Taylor Maid, he's been able to put his interest in human rights into effect, contributing to such organizations as Coffee Kids and the Foundation for International Community Assistance, groups dedicated to economic development in impoverished nations. "What would be a milestone now," Inman says, "is for companies like MJB and Folgers to go shade-grown." This is unlikely, though not impossible--Proctor & Gamble recently produced a product named Millstone, a certified organic coffee. Is this proof that the tide is turning, or merely that a limited market for organic coffees has developed and that some manufacturers are aiming to exploit it? The answer is probably a little of both. "The growth in organics, the reason that so many larger companies are coming around to it, is that they see that there is obviously a market for it. People are concerned about the chemicals they are ingesting," says David Griswold, president of Sustainable Harvest Coffee Company in Emeryville. Begun in 1995 as a brokerage operation that sources exclusively shade-grown coffees and provides the green coffee to organic roasters around the country, Sustainable is the first--and so far the only--brokerage with this shade-only focus. "The cup of coffee represents every sort of issue or element in the world," Griswold says. "You'd be hard-pressed to find another job where you can do this kind of meaningful work, work that is good for people, for the environment, where you can meet people like the farmers and pickers we work with, where you can feel excited about getting up every day. "You can probably take any product and use it to live out your own ethics," Griswold continues, "but with coffee, the issues are limitless." Drew Goings owns the Outland Java Company in Watsonville. Since he began roasting coffee in 1993, he's seen demand for organic coffees build to the point where more than 90 percent of his product is now certified organic. According to Goings, most of the buzz about ethics--from the bird-saving politics to the village-building efforts--is within the industry itself. Few of his customers ever mention such issues. "People like that it's organic," Goings says of his product, pointing with pride to an "unwashed" coffee--a product that protects the village streams where coffees are traditionally washed using methods that pollute the water systems. "I can't keep it in stock," Goings says. "They like the taste. When they learn that it's good for the environment, that's just an extra kick. I believe that the consumer, ultimately, will be the catalyst. If the consumer wants it, the importers will demand it from their growers." [ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.