![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

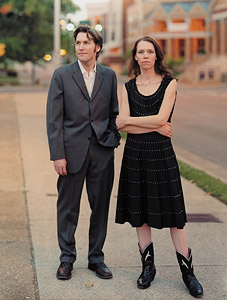

Photograph by Mark Seliger

Roots Seller

How former Santa Cruz songstress Gillian Welch beat the odds to become an Americana sensation

By Mike Connor

THESE DAYS, critics are raving that Gillian Welch is the New Hope of contemporary folk and American roots music, like some kind of down-home-storytelling, banjo-wielding Jedi. Two of her three albums have been nominated for Grammys. Her songs have been recorded by Emmylou Harris, and she performed on the multiplatinum, Grammy award-winning soundtrack to O Brother, Where Art Thou?, besides appearing in the movie itself and the subsequent concert film Down From the Mountain.

But it wasn't always that way. First, Welch had to put behind her all the suggestions that her citified self had no "right" to get within a coon's holler of the old mountain music. She had a tough time especially when she first began recording in Nashville, where she faced accusations that she was "faking it" from people who apparently think that Ralph Stanley's musical kill count--which at somewhere between 43 and 4,300 exceeds that of Ice-T, Ice Cube and Tupac combined--has an actual basis in reality.

"She got a lot of shit when she first started playing, because she wasn't a hillbilly," says her former band mate Mike McKinley of the Santa Cruz bluegrass band Harmony Grits. "Like you have to have black lung to write about mining. If she did all the things she writes about, she'd be dead by now."

So, yeah, Welch never killed a man in a stillhouse. She never ran a poker shack out in the swamp or wrestled a bear. She never even sold her soul to the devil at the cross- roads--or at least she won't fess up to it.

But as she returns to Santa Cruz, the very place she first began playing this kind of music, with a show at the Catalyst June 26, Welch is finally getting the props she deserves for the authentic sound she and longtime partner David Rawlings bring to their impossibly beautiful contemporary folk music.

Here Is Where It All Began

McKinley and the Harmony Grits have been playing in and around Santa Cruz for years, and while Welch was working her way through photography classes up at UCSC back in the early '90s, the band was playing regular gigs at Sluggo's pizza. Sort of a campus legend now, Sluggo's was the precursor to the Hungry Slug up at Porter College, and is still remembered for its buckets of beer.

"She would come down with her friends to drink beer, or sometimes just sit and do homework for part of the show," recalls McKinley.

"That was some of the first live bluegrass I heard, and Mike was actually the first one who played live Stanley Brothers records for me," says Welch.

McKinley lived in a communal house on the West Side at the time, and invited Welch to move in when a room opened up. "We started to get her going on bluegrass," he says, "and at one point she had a revelation, it's the story she likes to tell. It was a Sunday morning and I put on the Stanley Brothers. She came out looking really drained and she was like 'What is that?'"

Yet one listen to any of Welch's three albums reveals an intuitive feel for the music and a drawling voice steeped in the lilting, yearning voices of the Appalachian bluegrass legends: Bill Monroe; the Stanley Brothers; Blue Sky Boys; Flats and Scruggs. Tight, soaring vocal harmonies with her partner Rawlings loose a heart-stilling, purifying resonance.

What's striking about so many Welch songs is their power to affect the mood of a room. Say I'm listening to the bittersweet ballad "I'm Not Afraid to Die" from her second album Hell Among the Yearlings, and then my housemate turns to me and says something like, "Dude, I'm going to the market to get some smokes. Want anything?" I suddenly recognize the epic undertones of what he's saying, the interconnections between the journey to the store and the journey of life, and the ineffable sadness and nobility just below the surface of every human interaction, no matter how banal. Her songs are like that; they're like little pieces of myth, connected to a larger, sadder whole. It's difficult not to feel like Welch and Rawlings are playing the soothing soundtrack to your own little movie, you sad-eyed little drama queen.

Plaid Tragedy: The pioneers of bluegrass may have had it rough, but we bet they didn't have to put up with this upholstery.

'O Brother,' Hit Art Thou

Welch was also one of the most talked about artists on the soundtrack to the Coen brothers' O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which to date has sold 6 million copies worldwide. The record was 2001's runaway hit, snagging a Grammy along the way.

It sounds like a pretty big deal, but when I ask Welch if she had great expectations for the soundtrack's success, she replies simply, "I liked the record," thus steering the conversation away from the grandeur for which I'd been aiming.

"I mean, I really like that kind of music, as you can probably tell--that's my life's work," she says. "But we were just making the soundtrack for the Coen brothers' new movie. What's surprising about this is that Joel and Ethan Coen and T-Bone Burnett and myself made an album of songs that we liked, and so many other people liked it. If you'd asked me who the total think-tank, six-times platinum record-making team would be, me and T-Bone and Joel and Ethan is not what I would have come up with."

To some extent, making a hit record is a lot like rocket science. Nashville has been churning out prefab "New Country" stars like Garth Brooks and Faith Hill for years now, and some point to the success of O Brother as a sign that many fans are fed up with the formula and are pledging their allegiance to the roots-music movement that's been brewing just outside the mainstream.

"The people in Nashville want Faith Hill to be No. 1," says McKinley. "They want Tim McGraw or some prancing big hat, something you can take to the cash register. I hope [the success of O Brother] sends the message that they need to put out the right kind of music."

"T-Bone was really smart," says Welch. "He's the one who guided it through and didn't at any point ruin its chances, you know what I mean? He's the one that made sure that there wasn't a Shania Twain track on there. At the last minute, I was just waiting, I was just sure at some point someone from the record label was gonna come and say, 'That's great, but you know, if we could just put a Shania Twain song on there, we'd feel a lot more comfortable about how it's going to sell.' But that never happened, and I give credit to T-Bone for that."

A live performance of the soundtrack was filmed in Nashville as a benefit for the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. The documentary, entitled Down from the Mountain, also catches snippets of Ralph Stanley, with whom Welch performs live. Stanley's attitude about proprietary rights to the music is: "We were born in the hills way back in Virginia. [The sound] is born and bred. I don't think you can really get this sound unless you were born into it."

Certainly, when you're the biggest living legend in your chosen genre, you have the right to lay claim to it the way Stanley does. But like nearly all of the newest generation of roots musicians, Welch has an entirely different connection to the music.

"When I was a kid, all I knew was folk music, and it was 'This Land is Your Land' and Carter Family songs," she says, "which was the crazy thing about when I met Mike and I heard the bluegrass records, because I knew those songs, but I'd never heard the records. I'd been singing some of those old folk songs since I was a kid, but I'd never heard the Carter Family or the Monroe Family do them. That was part of why I freaked out so much that no one understands. I heard these records and I was like, 'Oh my god, what is this? This is the music I've known all my life.'"

Roots vs. Rock

According to Welch, everybody playing bluegrass and roots music today has a damn good reason to play it, because there's not a lot of money in it, and before O Brother, roots music had almost no mass exposure.

"I started going to Strawberry with Mike and the Grits every year, sometimes twice. That's when I really think I figured out that those people I was watching onstage there, that's what I wanted to do," she says.

McKinley remembers the Strawberry Festival days: "The first time I heard her sing was at Strawberry, and she had such a beautiful singing voice. We were sitting around a campfire and people just wander around playing and singing, it's an open-ended thing, and she just picked up her guitar and started playing."

"Until I bumped into that world of music, I thought that being a professional musician meant that you did what you saw on MTV, and I didn't do anything like that," muses Welch. "I didn't wear spandex and I didn't have big hair. I have flat hair! And so I think as a kid growing up and hearing heavy metal and glam bands and hair bands on the radio, it never really occurred to me that I could be a professional musician, until I really started hearing this bluegrass and American roots music world."

On their third and most recent effort, Time (The Revelator), Welch and Rawlings calmly put rock & roll to bed, as if all along it was just some red-faced 2-year-old looking for a bit of attention, and they tenderly return the child to the crib to rest while they play a few tunes. They pay homage to folk and bluegrass artists who stuck to their roots, even when the whole world wanted to rock.

Still, Welch cites bands like the Velvet Underground, the Pixies and Throwing Muses as some of her early influences.

"I've played rock & roll," she says. "That was probably one of the first times I performed in front of people, playing bass. We had a lead singer, so I just sang a couple songs. I pretty much looked like Jan Brady, I'd wear these little red, white and blue halter tops and little miniskirts and I had my glasses and these crazy pigtails, so I kinda looked like a whacked out Jan Brady sorta thing. Again, flat hair though."

It's easy to hear her penchant for rockin' electric guitars in the "implied arrangements" that Welch talks about on Time. Her banjo-playing on "My First Lover" implies a sonic wall of distorted electric guitar about to drop into the song like a squadron of Angus Young paratroopers, but it never actually happens.

"We hear all that stuff in our head. Like in my head, that's as close as we've done to an AC/DC song, really. We're headbanging when we do that, but we can't move around that much because of the microphones. That's a very Santa Cruz song. I would always picture West Cliff when I was writing that song."

I wish that I could somehow play Gillian Welch songs in your head now as you read this. To use a well-worn expression, it's a shame that we can put a man on a moon, yet I can't share the sparse and hauntingly beautiful sounds of Ms. Welch's music with 37,500 people via newsprint. She makes the kind of music that makes sharing it with others feel like an altruistic deed, like giving some wayward stranger directions to the best watering hole in town, where you know they'll get a cold beer and a hero's welcome when they get there.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

America's Most Haunted: Welch and partner David Rawlings put the spooky back in roots music.

America's Most Haunted: Welch and partner David Rawlings put the spooky back in roots music.

Photograph by Mark Seliger

From the June 26-July 3, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.