![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Swing Shift

It's always a beautifully cool day in Dave Brubeck's neighborhood of pioneering jazz sounds

By Rob Pratt

Young jazz fans quickly come to know Dave Brubeck. Even if their parents aren't enthusiastic fans of jazz, budding aficionados often find dust-veiled copies of the Bay Area-born pianist's Jazz Goes to College or Time Out among the record collections left over from their parents' youth.

Once a young person gets one of Brubeck's albums on the record player, the sound is instantly recognizable--Brubeck's cool-jazz style echoes in the upbeat melodies of John Costa, who accompanied Fred Rogers on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood for more than a quarter-century.

Despite the childlike nonchalance and serendipity of the sound, the music of Brubeck, who plays the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium Tuesday, is heady stuff. In the most famous recording by his quartet, "Take Five," composed by longtime Brubeck collaborator Paul Desmond, the group lays down one of the most difficult meters in music with effortless grace. Recorded in the same year as Kind of Blue, Miles Davis' breakthrough foray into modal jazz, "Take Five" similarly points the way ahead for avant-garde jazz with an extended modal vamp during the solo section.

Born in Concord and schooled in Stockton, Brubeck and his 1950s quartet, along with other California-based groups led by Gerry Mulligan, Shorty Rogers and Art Pepper, founded the West Coast cool jazz sound: pale tone colors, little vibrato and less-aggressive drumming than the engaged interplay common to bebop. With the addition of alto saxophonist Desmond to his trio, Brubeck earned national fame in 1952, culminating in 1954 with a Time magazine cover story.

Brubeck's cool, however, was a departure from the filagreed East Coast cool of trumpeter Davis, who pioneered the movement in jazz during a series of 1949 recording sessions later compiled into the album Birth of the Cool. Critics mistook the group's subtle swing for stiffness and misunderstood polyrhythmic experimentation as a fundamental inability to "keep time together" (as one critic wrote after a 1963 Carnegie Hall concert). Even Davis, long an admirer of Brubeck (who had a hit with the Brubeck composition "In Your Own Sweet Way"), wrote that Brubeck couldn't swing.

"Any jackass can swing," Brubeck says when asked about the critical backlash to his music. What he was trying to do, Brubeck explains, was to inject new sounds and rhythms into jazz and still make it swing.

And it did swing.

"And that's the answer right there is if you're reaching the people and they're feeling that beat, you swing," Brubeck recently told jazz critic Hedrick Smith. "And I've reached millions of people and they've been swinging and I'm still doing it."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

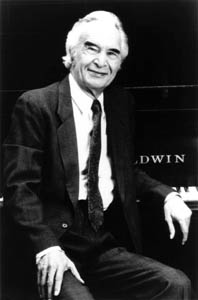

C'mon Get ... Happy?: Jazz innovator Dave Brubeck is either smiling or really angry with us. We can't tell.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet. Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium, 307 Church St., Santa Cruz, Tuesday at 8pm. Tickets are $60 gold circle, $35 and $25 general, available in advance at Logos and Ticketweb. 831.427.2227.

From the June 11-18, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.