No News Is Bad News

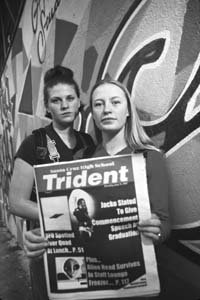

Full Court Press: Santa Cruz High School's student newspaper, the Trident, stopped publishing after Greta Hansen and Willow Bicknell were fired as co-editors-in-chief.

When Santa Cruz High School's award-winning student newspaper bit the dust this year, folks read between the lines that there are far more serious problems on campus

By Kelly Luker

WITH SUMMER UPON them, most kids and teachers are dreaming of vacations, barbecues and sweet relief from those bloody textbooks and exams. But at Santa Cruz High, many staff members and students are leaving school scratching their heads, wondering why their award-winning newspaper was shut down most of the year.

Many say the Trident--and the principles of independent journalism--ended up as casualties in a showdown between the faculty and disciplinarian principal George Pérez. Since Pérez's hiring in the fall of 1994, some teachers and staff have made repeated attempts to oust him. Mediators and therapists have been brought in to facilitate meetings between the sides. Almost two dozen teachers have transferred to Soquel High School since 1994, while last year the faculty gave Pérez a vote of no confidence.

The Trident stopped publishing after co-editors- in-chief Greta Hansen and Willow Bicknell were fired last October. The class responsible for its publication, advanced composition/journalism, lost more than half its students that semester, then was canceled in the spring semester due to lack of interest. A group of student leaders published an issue of the Trident in April, but few would compare it with the paper that was.

The newspaper's demise was symbolic of the bigger fight going on behind the scenes, and the issue, say observers, was the same--the right to free speech.

"We were the paper that other high schools were trying to copy," says Hansen. For a school newspaper, the Trident has surprisingly strong graphics and layout qualities. Most eye-catching, however, was its content--articles that reflected the harsh, controversial world that kids inhabit. There were hard-hitting pieces on AIDS and a student's account of a 15-year-old friend's suicide, along with first-person accounts of drug abuse, abortion, divorce and mental illness. Poems were interspersed with the feature articles and sports updates, including one chilling poem of a young girl's experience with date rape. Many of the issues are bilingual, an attempt to be inclusive of the campus's large Latino population.

For Hansen, the problems began when Trident adviser Jeremy Shonick transferred to Soquel High School a week before the beginning of the 1997-98 school year. Hansen had been involved with the paper since her sophomore year, working under Shonick variously as section editor and advertising manager until she and Bicknell were selected as new co-editors in time to put out the last issue for 1996-97.

When she returned to school after summer vacation, Shonick was gone, replaced by new adviser Ken Bowen. The tensions began immediately.

"We met with Mr. Bowen, and he told us that most of the ideas [for the Trident] were completely inappropriate," Hansen recalls. "He wanted more news and we wanted features and personal stories." Hansen and Bicknell, who were used to Shonick's style of guiding from behind the scenes, could not adjust. Students, parents, the adviser and administrators met more than once without success to try to work out the conflicts.

"One day in class, [Bowen] said, 'You can stay in the class, but I'm going to be looking for other editors,' " Bicknell recalls. "He gave us no warning, no probation-- he said, 'This relationship is not working.' "

Both Bicknell and Hansen dropped the class, and it dwindled from 15 students to six. School was out for the Trident.

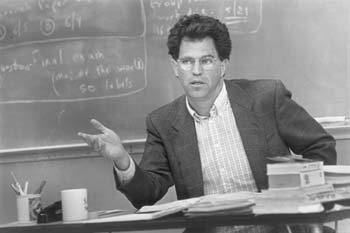

Blackboard Jungle: Former Trident advisor Jeremy Shonick cites acrimony between faculty and administration as a contributing factor to the campus newspaper's demise.

My Way or the Free Way

'THE TRIDENT IS A CLASS," Pérez explains. "There's a teacher and there are expectations." He would not comment on the specifics of what transpired between Bowen and the girls, citing employee and student confidentiality. But he says he's always had "total confidence in the advisers."

Although Shonick says he enjoys teaching at Soquel High School now, he admits, "It broke my heart to leave Santa Cruz High."

He leaves no doubt where he places the blame for his departure. "I felt forced to leave [by Pérez]," says Shonick. "I felt like I had no administrative support for anything I tried to do."

Shonick makes no attempt to hide the bitterness he still feels about the destruction of the Trident. "It was an exceptional paper because it was a student-run paper," notes Shonick, who served as the Trident's adviser for four years. He is particularly incensed at how the students were treated.

"They fired these kids?" Shonick says with amazement. "Isn't this what we're not supposed to do? The role of the teacher is to be a guide, not a jailer."

"My job was to advise [the students] and let them do it," he continues. "But from the get-go, Mr. Pérez didn't support the paper. He didn't believe in that freedom of speech."

Shonick is convinced that the power battles fought over the paper's right to free speech were symbolic of the deeper problems between the principal and his staff.

"I'm interested in a paper that discusses issues," says the former adviser. "But just as Pérez hated that about the paper, he hated that about teachers--that's what we've been telling the school board for years.

"I think you'll find the silencing of the paper reflects the silencing at Santa Cruz High," he continues. "A lot of teachers are running scared, planning to leave or have silenced themselves."

Shonick says that Pérez constantly fought for control of the paper, eventually forcing Shonick to take his case to the school board three years ago. Shonick says that the assistant superintendent in charge of curriculum, Sarah Gonzales, found in Shonick's favor.

Shonick is more than a little chagrined at the ad hoc paper that student leaders published in April. "That," he snorts, "was an embarrassment."

Indeed, the April 1998 edition of the Trident fell far short of the high standards set by previous issues of the paper--or for that matter, minimal standards for any high school. The paper was riddled with grammatical and spelling errors, featuring headlines like "The Admazing [sic] Hitchcock," "Is the Sentinel Prejudice [sic]?" and "Queans [sic] of the Hoop."

The issue's editor, Ryan Deane, stands behind it and his principal. "Nothing is George Pérez's fault," Deane states emphatically. "I feel like if I need him, he'll be there. He's been a mentor of mine." Deane mentions the decreased crime rate on campus and the one-to-one attention Pérez gives students to support his view of Pérez's positive impact on the school.

Deane paints a far different portrait than Hansen and Shonick of the problems behind the Trident. He believes it was a conspiracy by Shonick's co-workers that prevented the paper from being published.

"The teachers who were on Shonick's side didn't want the Trident to publish," says Deane, citing as an example allegations that teachers and other staff sabotaged Bowen's efforts by hiding desktop publishing equipment.

"Shonick didn't do jack," says Deane. "Kids missed deadlines, and Shonick was the one to let the kids go down to The Bagelry. No one always went to class--it was run pretty lax."

Hot Type, Cold Facts

ENGLISH TEACHER Nancy Migdall also holds Bowen blameless. Migdall says that Bowen "had his own ways of discipline." She is careful to not label Shonick as lax but says the kids would not follow Bowen's expectations. "It was these stupid little self-centered little brat things," says Migdall of the students' behavior in Bowen's class. "They would not follow directions like: Don't eat in class, don't wander around class."

That, combined with the students' unhappiness about Shonick leaving, resulted in a reaction, Migdall says, "typical of adolescence--they quit."

Reminded that the two editors were fired, Migdall still holds the teens at fault. "It was an extended tantrum that overindulged teenagers do," she says. "Look, I was in one of the meetings with these kids and their stories didn't match."

As far as Migdall is concerned, the changes that Bowen instituted are typical of the real world of newspapers and not about censoring or repression. A new boss has the right to change direction, she figures, and it is up to the employees to decide whether they want to go along or go away. The English teacher believes that Bowen was a pawn in the problems that ensued. Bowen did not return several phone calls for this story.

Both Shonick and Bicknell deny ever missing a deadline for the Trident. Shonick laughs at the allegations that kids wandered around campus. "No good newspaper works like a regular class," he says. "Reporters need to follow their stories, and that means they have to be out interviewing people."

Migdall also does not give the Shonick-advised paper particularly high marks. She is quick to note that the paper won awards under Julie Minnis, not under Shonick. As far as Migdall was concerned, the paper's content was "self-indulgent."

English teacher Minnis is the one who brought the Trident under the auspices of the English department, instead of applied arts. With Minnis as adviser from 1989 to 1994, the paper won 27 state and national awards for excellence. A wall of her office is filled with impressive plaques and award certificates.

"I attempted to guide students to meet a journalistic standard," Minnis says. "I wanted the quality to not be tied to the editors but to the paper."

The English teacher felt comfortable passing the torch to Shonick, who continued the hands-off style of guidance. Contradicting Migdall, Minnis says the paper fell apart after Shonick left, not before.

"I feel dreadful that our editors were not supported," she sighs. "I was the lone wolf. But that decision [to fire the girls] was about people, not about the paper. And the paper was sacrificed to make people look good."

Asked how things are now, Minnis looks away.

"Life is uncomfortable under this [Pérez's] administration," she says.

A walk through Soquel High School halls and offices finds other teachers who, like Shonick and Minnis, found it uncomfortable at Santa Cruz High.

Sandy Augustine's voice starts to shake as she discusses her tenure under Pérez. A school counselor for two decades, she recently transferred to Soquel High from Santa Cruz High.

"After some 20 years, these last three years were the first and only three years I felt intimidated," says Augustine. "[Pérez] is extremely threatening, both publicly and privately."

Augustine talks about Pérez moving her office, taking things out of her secretary's desk, rearranging student caseloads, making adjustments in master schedules--all without prior discussion or notification. Halfway through our discussion, she stops abruptly.

"I can't talk about this," she says, voice quavering. "It's still too painful."

School of Hard Choice

PÉREZ INITIALLY REFUSES to answer questions, brusquely claiming employee or student confidentiality. His phone voice is clipped and short, offering no room for negotiation. However, he quickly agrees to meet in person, which we do on two separate occasions. Sitting behind his desk, Pérez cuts an authoritative figure. A compact man with a neatly trimmed beard, he smiles often. Although he is a little more responsive than on the phone, Pérez answers almost every question with a dismissive laugh, a response that has an oddly disquieting effect over a period of time.

Pérez denies interfering with the Trident, but says that he would step in if he thought the paper contained too much profanity. "I deal with the kids when I have a problem or issue with the paper," he says. The principal says he never tried to take control away from Shonick and does not remember any meeting with assistant superintendent Sarah Gonzales.

(Shonick questions Pérez's recollection, producing the documentation from the meeting that includes a memo from Pérez demanding final review of the paper before it goes to the printers. "He will often say he can't remember--that's very typical of Mr. Pérez." Shonick also says that "the issue of profanity was never raised to me by Mr. Pérez.")

The principal notes that there has been an effort every year to remove him, but he blames it on "a few disgruntled people here." He denies being autocratic or intimidating. But Pérez agrees that people have strong opinions of him and his style.

"When I came here," says Pérez, "parents and staff were asking for a strong administrator." And for good reason. As one teacher puts it, things around Santa Cruz High by the spring of 1994 were "hellish." Gangbangers, racial tension and reverberations from restructuring--a new approach to teaching that was replacing traditional lecture methods--had left the campus in disarray.

"My directive was to pull it together," Pérez continues.

"I have a highly intelligent, intellectual staff that is not afraid to express their opinions," says Pérez, then adds with a grin, "That's great for the kids, but it doesn't make my job easier."

About 20 Santa Cruz High teachers have migrated to Soquel High during Pérez's tenure. Pérez believes it is for a myriad of reasons, including that some teachers live closer to that campus.

As for last year's vote of no confidence, Pérez is nonplused. "That's their opinion," he shrugs. The bottom line, as far as he's concerned, is the vote of confidence that kids and their parents give him.

"I am student-centered," asserts Pérez. "And we're now the school of choice with parents."

Wrong Numbers

IF SOME TEACHERS GIVE their principal a failing grade, he gets high marks with moms and dads. "I think Mr. Pérez has done an outstanding job," says Joe Reyes, father of two SCHS students. "He's doing his job, and I know some of the teachers don't like that--they think they should run the school.

"It was horrible there," he continues, "and it changed after Mr. Pérez came."

Parent Kevin Dempsey agrees: "Things were out of control [at Santa Cruz High]. When [Pérez] came along, he instilled an attitude that that wouldn't be tolerated anymore."

Dempsey, who is also president of the high school's Band Boosters, adds, "The campus has become cleaner and friendlier, and the kids have become more polite."

Administrators at many high schools are little more than ciphers to the students streaming through the hallways. However, Pérez is acknowledged by both supporters and detractors as involved with the kids. Football games, drama shows, band concerts--George Pérez will generally be found in the audience.

But discipline is a double-edged blade, and it is not unusual for folks in power to wield it more like an ax than a scalpel. With that approach, there are bound to be some victims of friendly fire. Shonick is convinced that it is not just individuals, or the campus newspaper, but the system itself at Santa Cruz High that has suffered.

"The teachers are tense," he says. "When there are repercussions in terms of scheduling and room assignments, you don't have a healthy workplace.

"If there's a message to be learned here, it is that you have to have a democratic process," Shonick says. "And I feel that's what has been lost at Santa Cruz High. And if you don't have that, you don't have a healthy school."

Santa Cruz High math teacher and recently elected Santa Cruz City Schools teacher's union president George Martinez has kept a tally of teachers that have left his campus in the past eight years. A numbers guy, he can give exact percentages: 33 percent of the teachers left in the four years before Pérez, 52 percent left during his tenure.

Like Pérez, Martinez notes that the increase may be due to other factors: the aging of the faculty or the institution of a more work-intensive schedule known as Excel. But, as the no-confidence vote signals, dissatisfaction with Pérez rates right up there. However, the migration of teachers does help Pérez's assertion that the number of unhappy teachers under this principal is small--"and getting smaller," says Martinez with a rueful laugh.

Although Pérez may be popular with parents and students, Martinez notes that it is not the principal who teaches the students. He is referring to the teachers who have decided to stick it out under George Pérez.

"Do the kids benefit from the teachers or from the principal?" Martinez asks. "And, will the kids of tomorrow benefit?"

Pérez emphasizes that his faculty is now "actively recruiting" students to work on next year's Trident. The more important question in other minds is, just what kind of newspaper will it be?

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

George Sakkestad

From the June 4-10, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)