![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Ride of Passage

Andrew Pham left Vietnam as a child in a leaking boat and returned 20 years later as a grown man on a bicycle. His new book reveals the secrets of his family's past, the heart of humanity and the deepest wounds of war.

By Jesse Douglas Allen-Taylor

I CAN REMEMBER the first time someone tried to convince me that Vietnamese were real, human people and not just subjects in a newspaper article or the objects of somebody's Great Cause. It was the fall of 1965, the year of the introduction of U.S. ground troops into Vietnam. The drumbeats of war were fiercely booming across the nation. The message from newspapers and the evening news was incessant: the South Vietnamese were a peace-loving, gentle, farming people being assailed by vicious hordes of Communist cadre known as the Viet Cong. Our help was desperately needed.

"There's no such thing as the Viet Cong," journalist Robert Scheer told us from the steps of the old Merritt College in Oakland. "They are really the National Liberation Front. Calling them a name like 'Cong' is just an attempt to denigrate Asian people, part of the old Hong Kong, ching chong, ricky-ticky stereotype. It's the government's way of dehumanizing people they want us to kill."

Scheer made his speech when the American antiwar movement consisted of little more than a handful of hippies and peaceniks. His remarks weren't well received, even in Oakland. The white frat boys--already primed for buzz cuts and combat boots--hooted in derision. The black students listened attentively but walked off indifferently. We had image problems of our own to deal with.

Thirty-four years later, after the lives of an entire generation of American soldiers were mangled, altered and intertwined with this Southeast Asian nation, and with thousands of Vietnamese descendants now living as our neighbors and fellow citizens, the South Vietnamese story of the war has gone largely untold. Many Americans still view the Vietnamese as a mysterious people. Self-sufficient and largely silent about the torments of the war, the Vietnamese remain to many like rice-paper cutouts within stereotypical beliefs.

Andrew X. Pham has no such problem. The 31-year-old journalist, Vietnam native and U.S. citizen lived through Saigon's fall to Northern armies, escaped Communist Vietnam with his family in a sinking boat and spent his teenage years assimilating into American culture in Northern California. His recently published Catfish and Mandala is an account of Pham's journey into his own psyche and into the land of his birth.

He shows Vietnamese as people like all people, neither all good nor all bad but somewhere in the middle. The sometimes harshly stark and sometimes tearfully beautiful portraits of that humanity make Catfish and Mandala both a memorable read.

"It started out originally as a travelogue of my trip back to Vietnam," Pham says. "But travelogues don't allow the author to put in his own thoughts and say why he went on the trip in the first place. So I decided to make it a larger work."

Larger, indeed. Catfish and Mandala comprises both an account of Pham's 1996 bicycle tour of Vietnam and Japan and a series of flashbacks to his family's journey from Vietnam to Louisiana and, ultimately, to Northern California.

Writing Toward Wisdom

THE LITHELY MUSCULAR Pham--who rode his saddlebag-laden bicycle out of California, packed it onto a plane and landed to ride it around the Pacific Rim--genuinely does not seem to understand the great impact of his story, asserting in our interview with a little smile that he doesn't think anything very exciting happened to him during his return tour of his homeland. That, however, is clearly a matter of perspective.

Among other hazards on his journey, Pham writes that he had to duck the Vietnamese police, just missed being caught in a smuggling bust after helpfully holding someone's package of illicit cigarettes and far too often had to flee from murderous mobs, once being saved by a posse of machete-wielding local citizens. It is the price he pays, he writes, for being a Viet-kieu, a "foreign Vietnamese," and therefore an easy target as an outsider.

But, then, Pham must be forgiven for having a slightly higher threshold than most for what constitutes an interesting life. After the Communist takeover of Vietnam, Pham witnessed his father's prison-camp incarceration and near death in mine-clearing operations, and lived through his family's harrowing ocean escape from the country in a leaking boat. Not to mention his days as a wannabe ethnic gangbanger at San Jose's Andrew Hill High School, doing battle with the "Mexican cholos" and the jocks, part of his teenage struggles both to forge an independent identity and to fit into life in a strange new land. All of these are recounted with an expert storyteller's touch in Catfish and Mandala.

Pham's sense of harrowing adventure as a natural course of life is a gift, allowing him to present the most intensely dangerous situations in such a matter-of-fact way as to make them especially chilling. Of his father's experiences in prison camp, he writes:

[My father] was to clear a straight path [through a minefield] for the log team. He hunched down low and began parting the grass one cluster at a time, searching for the black trigger rods of the canister and ball mines. He probed the ground with his fingers, praying to the gods he didn't believe existed that there were no pan mines in his path. ... He found two canister mines and marked two parallel paths, fifteen yards apart, with ropes. It was the loggers' turn. Everyone else took cover. Six men pulled on two ropes tied to opposite ends of a log. ... Eyes quivering on the edge of hysteria the loggers trembled, looking like overworked nags strung out by the scent of slaughterhouse blood. ... An explosion rent the air. ... The VC replaced [the injured loggers] with two others and a new log. The work went on until sunset.

He writes about his own experiences in those chaotic days of 1975 while the last American Marines were scrambling to helicopter safety from the rooftop of the American Embassy and the North Vietnamese army was triumphantly entering a crumbling Saigon. In the explosive confusion in the streets of the capitol, 8-year-old Pham had to flee from bullies trying to steal an army-discarded pistol he had found:

Then I burst onto the street. Crashed into the flood of refugees swarming in one direction. Refuse covered the ground, stampeded over and over again. The air reeked of smoke, loud with people. Down the road, the fish market was burning unchecked. Gunfire snapped in staccato across the city. Somewhere far away a siren howled. Above, red zipping bullets crossed the night. The sky ruptured with false thunder. Dull flashes of light bruised the city skyline. Growling helicopters skimmed low, their humping air vibrating my ribs, their rope ladders trailing behind like kite tails. I dove into the tide and was swept along with it.

But Catfish and Mandala is by no means merely a dark passage through pain. Pham also has the standup comedian's timing and ability to toss in memorable anecdotes almost like throwaway lines. His account of the Vietnamese cobra drink makes the worm-in-the-tequila thing seem like, well, schoolboy stuff, and after reading his tale of the catfish living in the water at the bottom of the latrine, readers may never sit on an outdoor toilet with quite the same confidence again.

Worlds Apart

MUCH OF Catfish talks of the difficult bridge from being Vietnamese to being American. Relatives engage in a rock fight when the old tradition of respect for elder brothers breaks down. Pham's father disciplines Pham's older sister, Chi, in the way he has been taught, caning her unmercifully. But a schoolteacher observes Chi's bruises and calls authorities, and the father is arrested. The book is partially dedicated to Chi, whose suicide propelled Pham into returning to his native country to determine the source of her discontent and to untangle his family's angst.

Pham says he sees a Vietnamese people in deep transition, both in Vietnam and here in America, twisting back, snakelike, almost in direct contradiction of themselves and their traditions. He points out the contradiction in his own life, saying that he is "always more Vietnamese than I think and less American than I hope."

"The far right wing of Vietnamese in America is very vocal, but it does not represent the majority view of the community," he says. That is often masked, he explains, by the fact that the anti-Communist minority is so forceful that it often sweeps up the rest of the community with it.

Pham's portrait of Vietnam itself, drawn from the observations of his journey, also shows a nation seemingly at odds with itself.

"I expected to find a more totalitarian regime," he says of his return visit. In his book, he describes a country that has almost given up on controlling its people. At one point, he writes, travel between the provinces was carefully monitored. Now the border booths go unmanned, and the drop-down gates only serve as teeter-totters for children. These days, police in Vietnam seem to spend much of their time trying to get themselves bribed. "They'll peel and gut you for everything you have," he is told.

"You've got to understand, Vietnamese have always been capitalists, and that's what they are now in Vietnam," Pham says. "Capitalists in the sense of wanting to make money. Even the government officials. Anyway, there are too many people in the country to try to watch all the time."

But perhaps Pham's most unexpected discovery in Vietnam--unexpected for non-Vietnamese--is that even after running off the French and the Americans, many Vietnamese citizens still harbor the old peasant/colonial feelings of

inferiority.

Pham recounts that when he announces to his Saigon cousins that he is planning to bicycle alone from Saigon to Hanoi, his relatives immediately try to dissuade him, one of them insisting that "Vietnamese just don't have that sort of physical endurance and mental stamina. We are weak. Only Westerners can do it. They are stronger and better than us."

And yet at the same time, one of the more interesting national exhibits in Vietnam, as recounted in Catfish and Mandala, are the elaborate underground tunnels that the Communist armies lived in while preparing for their final assault on Saigon, three-level labyrinths in the living earth, a monument to a national courage and stamina that stretches the human mind to imagine. That Vietnamese people can hold both their victories and the superhuman effort that it took to bring them about in one hand, and their sense of the West being bigger and better in the other, is a dichotomy that is peculiar to observe.

"Fighting the war took a tremendous collective effort," Pham now says in an attempt to explain. "Vietnamese have no trouble seeing themselves accomplishing something when they can rally as a group, but they do not think of themselves as accomplishing much as individuals. As individuals, they look at the world from a position of physical inferiority. I mean, the average Vietnamese man is something around 110 pounds. Beside that, Westerners are so big."

Verse Engineer

OF COURSE, Andrew X. Pham is a study in a bit of peculiarity himself. He graduated from San Jose's Andrew Hill High in 1986, then majored in aerospace engineering at UCLA, achieving his B.S. in 1990. But he views his entire college career a little sheepishly. "I went into engineering because I wanted to fly," he says. "I didn't find out until too late that engineers don't fly. I should have studied to be a pilot. I did get a lot of free passes out of it on United Airlines, though."

He took a job at United out of college and that is how he ended up writing.

"At United, we had the chance to eat in a lot of restaurants around town," he explains. "I used to follow all the local food critics around. I'd eat at the same restaurants and read their reviews, and I finally said, 'Hey, I can do that!' It wasn't that hard, because there weren't a lot of experts on Asian food in the area. So I started freelancing food reviews."

Pham quit United when, as he chronicles in another of the book's ironically funny passages, he realized he would never fit in as the "good Oriental ... good worker ... [g]reat in math, the engineering stuff" his boss expected of him. Instead, he began honing his writing skills as a freelancer. In all, he wrote for nine years, producing one unpublished novel and a whole host of reviews, before the publication of Catfish and Mandala.

But amazingly for a man who plays words like the finest instrument, he seems irrepressibly self-conscious about his writing abilities and laments that he holds no formal training in writing and belongs to no writers' groups. And most remarkably: "I'm not really conversant with English," he says.

He took a year off work to write Catfish and Mandala. By the time he was finished, he was down to his last $40. Though publication has not changed Pham's unpretentious nature, it has given a bit of breathing space to his lifestyle. He expects to make enough money from the book to last a year or two. Presently living in Portland, Ore., he says he will spend the next couple of years in Mexico, working on a second novel. He has some ideas for the next book, but won't reveal them.

War Wounds

PHAM ADMITS that the writing of Catfish and Mandala was a personal catharsis. But although his book is an account of Pham's own reconciliation with his past and his ethnic background, it also opens a doorway of healing of the great wounds in the souls of all those people touched in one way or another by the war in Vietnam. Pham's own father had once commanded 2,000 propagandists for the South Vietnamese army, and Pham's early sympathies were clearly anti-Communist.

But the most moving accounts of the book are his encounters with an aging, one-legged Viet Cong veteran and with an American soldier in the Mexican desert, melancholy with guilt over his role in the war. Of the American veteran Pham writes, "His Viking face mashes up, twisting like a child's just before the first bawl. It doesn't come. Instead words cascade out, disjointed sentences, sputtering incoherence that at the initial rush sound like a drunk's ravings. Nameless faces. Places. Killings. He bleeds it out, airs it into the flames, pours it on me."

"Tell them about me," the soldier says when Pham outlines his pending trip to Vietnam. "Tell them about my life. ... Tell them I'm sorry."

Nearly a year and a half and a world away, Pham's book recounts the Viet Cong veteran's answer: "No, I do not hate the American soldiers. Who are they? They were boys, as I was. ... These hills where I've killed Vietnamese and Americans. I see these hills every day. I can make my peace with them. For Americans, it was an alien place then as it is an alien place to them now. These hills were the land of their nightmares then as they are now. The land took their spirit. Tell [your friend]. ... There is nothing to forgive. [H]e is welcome here. Come and I shall drink tea with him, welcome him like a brother."

Pham appears to have no ax to grind--no political agenda to push--only a deep desire to seek out the truth in his own existence and lay it bare for himself. If in the process he lays the truth bare for the rest of the world, that is so much the better. The larger purpose to his writing appears to be a search for reconciliation through understanding. In this, there should be no surprise. It is almost certainly those who have suffered the most through the ghastliness of war who can best show us the difficult pathway to peace.

Andrew Pham reads from Catfish and Mandala on Thursday (May 18) at 7:30pm at Bookshop Santa Cruz. Free. (423.0900)

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Life Cycle: Andrew Pham toured his homeland on a bicycle with a general itinerary to travel the countryside, often camping out in parks and open space areas such as this one above.

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Photograph by George Sakkestad

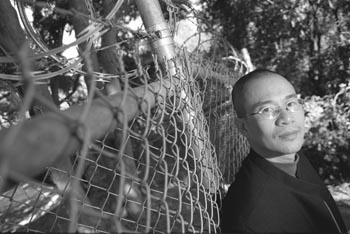

Unbound by Tradition: Pham writes about the struggle to reconcile the ideals taught to him as a child in Vietnam with the values he acquired later in America.

Time Passages: A photo from Pham's travels captures the essence of his return to modern-day Saigon, where he ventured into the alleyways and living spaces of his childhood to solve the mysteries of his family's past.

Time Passages: A photo from Pham's travels captures the essence of his return to modern-day Saigon, where he ventured into the alleyways and living spaces of his childhood to solve the mysteries of his family's past.

Catfish and Mandala

By Andrew X. Pham

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25,

336 pages

From the May 17-24, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.