![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Short Sharp Shocks

Local poet Gary Young pulls verse out of chaos

By Stephen Kessler

'I WANTED TO WRITE a book about my mother," says Gary Young of his acclaimed book of prose poems Braver Deeds. "I knew if it was going to be about my mother, it was going to be about violence. My lover Kitty was dying of cancer, and I was taking care of her at the same time that my mother kept attempting suicide with greater and greater frequency, and finally they died within months of each other. And that was such a bizarre thing, and it was right after I'd had surgery for cancer.

"So there were all these people dying, and people were having overdoses and killing themselves ... I think I lost more people in my life from the age of 27 or 28 till 31 or 32 than the rest of my life combined. So I wrote a book about that--about how we're all dying, we're dying all the time, and how waking up and getting out of bed in the morning can be such a cruel thing, it's so hard--such a violence, you know--people have to wake up and be themselves. It's too much sometimes."

Too much indeed. In the barely controlled yet plainly fertile chaos of Young's writing studio, situated above his print shop in the Santa Cruz mountains, the evidence of too-muchness abounds: bookcases overflowing onto the floor, books heaped on tables and chairs, piles of ripped-open envelopes and unanswered correspondence, stacks of his own framed original artwork leaning against furniture, family photographs hanging askew on walls. It is the work space of an artist whose life is so richly interesting and demanding in its everyday essentials and distractions that he scarcely has a chance to appreciate how much he has accomplished.

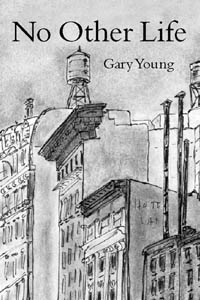

Husband, father of two boys, master letterpress printer, longtime teacher, much-collected visual artist, award-winning poet, Young at 50 is in his prime. His trilogy of recent works--Days, Braver Deeds, and If He Had--has just been published in a collection called No Other Life, which he'll read from on Thursday at Bookshop Santa Cruz.

"I'm basically a lyric poet," says Young. "That's what I want poetry to do: I want poetry to stop time. To make us see something so clearly [that we understand] 'I'm actually seeing this, I'm actually feeling this, I'm actually thinking this.'"

The poems in Young's earlier books, Hands and The Dream of a Moral Life, were lyrical but discursive, skillfully written yet formally conventional verse. But in Days, he turned to a radically brief form of prose poem that in its spare lucidity leaves afterimages burned into the reader's imagination. A typical piece reads in its entirety:

The miracle of the everyday event is a recurrent theme in Days. It is a book full of light, a book Young says he had to write before going into the darker material of Braver Deeds, winner of the 1999 Peregrine Smith Poetry Prize.

Braver Deeds is a work of extraordinary strength, not just for the difficulty of its subject matter and the poet's courage in exploring it, but for the formal grace and mastery with which he engages pain and loss and grief, telling whole stories in a few lines, small paragraphs resonant with immanence and implication. Some 60 of these little narratives of life and death--often violent, often horrifying, yet somehow consoling in the clarity with which they confront reality--give this book a cumulative power rarely encountered in contemporary writing.

Forced by circumstance (with the birth of his first son, "there was no time to write long poems") and impatience with his own accomplishment in verse ("What was bothering me about my work was that I felt like I had gotten really good at something ... and so I started getting suspicious of my own stuff ... it started to feel manipulative"), the poet turned to a condensed prose and attempted to pack as much meaning as simply as possible into a very tight space. The brevity, the compression required of this approach, reflects among other things his sense of our limited time among the living.

The final book of Young's trilogy, If He Had, is organized around the death of a 5 year-old boy, the son of friends. "The book is about dying," he says, "is about what happens to us--and in the meantime, here we are. Here we are, waiting to die, and it's not easy, but it's almost continually amusing and beautiful and terrifying and astonishing." The astonishment is a response to both the mystery of seemingly ordinary events and the even more vexing mystery of the unimaginable. "I always thought that was the definition of imagination, that, 'Well, I can imagine anything.' And what I discovered in trying to write this third book was that there are limits to my imagination, that there are some things that I just can't imagine."

And yet despite the tragedy at the heart of If He Had, there is also a sense of redemption and inspiration, of art capturing life at its most uncontrollable and squeezing out of it a sweetness that might otherwise go unnoticed:

The poet's vision is like the child's innocence in its capacity to transform cacophony into song.

No Other Life, the completed trilogy, could well turn out to be a minor classic, a work that outlasts its time. But Young says that's not what he writes for. "It doesn't matter how long art is, because life is still short ... and that's why the idea of doing something for posterity I find more than ludicrous. You write poems because it's a good thing to do right now. Because if you're not doing something right now, you're wasting your time."

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

The Good Die, Young: The acclaimed local poet reads at Bookshop Santa Cruz Thursday.

Two girls were struck by lightning at the harbor mouth. An orange flame lifted them up and laid them down again. Their thin suits had been melted away. It's a miracle they survived. It's a miracle they were ever born at all.

That winter, when we lived in the city, sirens and car alarms screamed outside our window every night, and each time they did, our son, who had lived his whole, short life in the mountains, would smile, turn his head toward the street, and say, bird.

Gary Young will read from 'No Other Life' Thursday, May 16, at 7:30pm at Bookshop Santa Cruz.

From the May 15-22, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.