![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

Rolling Over Beethoven

Long live the New Music Works revolution

By Scott MacClelland

AFTER YEARS of slaving away at presenting classical music that actually matters, New Music Works' artistic director Phil Collins probably had little clue that his vision was on the verge of finally winning the respect it deserved. But a full-house audience last Saturday at Veterans' Memorial made it clear that Collins' time has come.

New Music Works has been getting it done around here for quite a while now. At first glance, the Cabrillo Music Festival and UC-Santa Cruz would seem to have provided fertile local ground for the cause of new music, but somehow they've both fallen short of Collins' sharply defined dedication to innovation and originality among--principally--important West Coast composers.

But something far more significant recently took place that was entirely beyond Collins' control: The classical music recording industry died. Many of today's biggest concert artists have turned over their recording contracts largely to crossover or folk or pop, among them violinist Joshua Bell, cellist Yo-Yo Ma and guitarist John Williams. As classical orchestras (outside of the largest metropolitan areas) are finding it harder and harder to attract younger audiences, new music has suddenly taken off. Specialists in the field, including the big names like Philip Glass and the Kronos Quartet, will attract ticket buyers who never go to classical concerts. It's as if the end of the 20th century closed a door between the older generation that now uses classical radio as background music and a younger breed who are hungry for live, new concert music no matter how ultimately ephemeral it may be.

Out With the Old School

Collins' concert last weekend nailed all this home even harder than intended as it punctuated a new-paradigm program of Lou Harrison, Dan Wyman and Allen Strange with a rapidly fading echo of yesteryear, Hans Werner Henze's guitar concerto "To an Aeolian Harp." An audacious lion of new music during the 1950s and '60s, Henze sounds in this 1986 piece like a tired rehash of Arnold Schoenberg in the second decade of the 20th century. The work is both atonal and structurally obscure, a formula that forces the listener to work hard to get it. This was no fault of the performance by soloist David Tanenbaum or the orchestra under Collins' direction. Henze's technique, like Schoenberg's, was to use a highly colorful orchestra in place of tonal harmonies and classical architecture.

While it has been popular in recent years to inflect (and soften) music like this with "romantic" phrasing, Collins made no such concessions, allowing the music to speak through his musicians. While Tanenbaum pulled off a faithful commitment to his concertante role, the 15-piece orchestra, including low flutes, strings from the violin and viol families, oboe d'amore, harp and percussion, created an often-dense, sometimes self-annihilating texture that craved more air than the composer allowed it to get.

In With the Lou School

Tanenbaum got his real chance to shine in Lou Harrison's Scenes from Nek Chand (2002), a solo in three movements for National steel guitar, a full-bodied slide guitar that gave the artist many opportunities for expressive portamento, that sensual component of Asian music that Western classical rejects almost universally. Harrison calls the movements Leaning Lady, Rock Garden (a 'stampede' dance) and Sensuous Arcade, all inspired by sculptor Nek Chand's astonishing rock garden in Chandigarh. Like much of Harrison's music, the finale fashions improvisations on a mode.

Harrison's Music for Violin and Various Instruments (1967) featured an extensive solo by violinist Cynthia Baehr, with each of the other four musicians alternating on mbira (thumb piano), percussion, keyboard and psaltery. (A drone provided a "rudder" for some of the violin melodies, as Harrison explained during a preconcert talk.) Even when meditating, Harrison's music graciously finds a way to define a beginning and an end, a no-brainer that inexplicably manages to escape the consciousness of many contemporary composers.

Despite its extensive Webern-style aphorisms and lack of repetition, DanWyman's Discourse: Beyond Words (2002) for saxophone and chamber ensemble framed its 20 concentrated minutes with a clear point of departure and, ultimately, a jazzy dance reminiscent of Milhaud's Creation of the World. William Trimble led the dialogue from the soprano sax in this NMW-commissioned world premiere. (More than any other this worthy work seems to have inspired the program's title, "Free-Range Viruosities.")

Allen Strange's King of Handcuffs, a thoroughly witty "Ragtime for Harry," capitalized on the jocular minimalism of John Adams (as opposed to the grimly determined variety by Steve Reich and the mind-numbing noodlings of Philip Glass). With violin, cello, flute, clarinet and percussion under Collins' lead, tenor Brian Staufenbiel--suited up like a New York street cop--recited the legendary tale of Harry Houdini, stripped naked and searched, then handcuffed and shackled, only to free himself within four minutes to the amazement of a cohort of constables.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

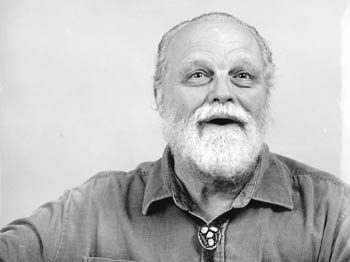

Lou Really Got Me: Harrison's newest composition was the 'pièce de résistance' of New Music Works' last program.

From the May 15-22, 2002 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.