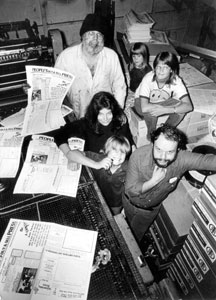

Photograph courtesy of Jenny Heth Inking for Themselves: The People's Buy and Sell Press was a family affair. Shown here, clockwise from top, are founder Jim Heth; Nancy and Jenny, his daughters; Peter, his brother with whom he ran Staircase Theatre; John, his son; and Kathryn, his wife. Standing on the Shoulders of Giants Sooner or later, we all ask, 'Where did we come from?' and 'Why are we here?' In an attempt to provide an answer, Metro Santa Cruz presents an oral history of the Santa Cruz alternative press leading up to our own birth 10 years ago. For those who used to write, we salute you. By Mike Connor Yes, we know you have cats older than us. But unlike your old cat, who smells, Metro Santa Cruz smells nice (go ahead and smell us--that's the sweet, inky smell of success!), and has managed to slug its way through 10 years of slings, arrows and outrageous economic downturns. Your cat just sleeps all day. Ten years may seem like a piddling moment in the grand procession of human history, but in the grand scheme of Santa Cruz alternative newspapering, 10 years is like freaking millennia. Indeed, it's easy to gawk at old issues of the Free Spaghetti Dinner--a paper many consider to be the Grandparent of Santa Cruz alternative journalism--as if it were some sort of primitive buffalo cave scrawl. Except that the art in the FSD is psychedelic and sophisticated and funny, and the editorial content is politically and emotionally charged with radical progressivism. In short, it's '60s Santa Cruz counterculture in print. Its successors are equally compelling and undeserving of Early Man metaphors. From the FSD and Sundaze in the late '60s and early '70s to the Sun and Santa Cruz Magazine in the late '80s and early '90s, Santa Cruz has a rich tradition of some of the most masochistically iconoclastic journalism this side of ... well, there probably ain't nothing else just like it anywhere. What follows is an oral history of some of the greatest alternative newspapers of their time and place, as told by some of the people who put their hearts and souls into the arduous and glorious task of producing a newspaper. For those of you who were there, get ready for a trip down memory lane. For those of you who are newer to town, take heed, for these are the voices that shaped the town you call home.

1968-1970

Rick Gladstone: The Sentinel was painfully conservative, it made my brain ache to think of how conservative the Sentinel was. And the Mercury was the same way back then, extremely provincially conservative and fundamentalist in religious ways. Reactionary. We were self-deprecating, because there were a lot of things to take seriously. The Vietnam War was slaughtering people, and the reactionaries wouldn't give an inch to people who lay claim to a piece of the pie without bleaching their skin, cutting their hair and getting on their knees and singing the song of the Man. Futzie Nutzle: The Balloon was me, henry humble and Spinny Walker. It was about humor. And nonauthority. It wasn't specifically political, we didn't relate to any particular direction or party, but all three of us had axes to grind considering our outlook. henry had just gotten out of the army, and Spinny was kind of a loose cannon. Spinny started it, I think he just walked into the studio one day with his masthead, and we liked it, but we thought Balloon needed two "L's" instead of one. I think he just cut it up and pasted it back together. We had no money, we just had the spirit and the inspiration to do [the Balloon Newspaper]. We had paper, ink, a few pens and a radio. Everything went into the production of art, all of our energy and all of our time. We were living in some turkey coops where Dominican Hospital is now; it was kind of self-sufficient because we had a garden out there and everything. That was the old Santa Cruz. Rick Gladstone: It's like we were using chisels and hammers and shit, that's what it feels like, looking back. It was just so much work to get [Free Spaghetti Dinner] out. In '67, Tom Scribner, John Tuck, John Sanchez and some others, we were in Tom and Mary's kitchen. We were trying to be very subversive, and formed a newspaper called the Ripsaw. Tom had some experience, he was very left wing and had done some labor organizing. We did that for about six or seven issues, this cheesy little four-page offset thing, speaking out against the war in Vietnam and commenting on the domestic student and African American rebellions that were going on. About two years later, some friends and I started the Free Spaghetti Dinner. We tried to put together something that was substantial and had some legs. The first Free Spaghetti Dinner, it was named because the first meeting in our house, we cooked spaghetti. There were about 13 people sitting around stuffing themselves with spaghetti, and we said, 'What are we gonna call this thing?' We decided on Free Spaghetti Dinner because it was so absurd, very dada-esque. Jenny Heth: I was nine when [The People's Buy and Sell Press] started up in Ben Lomond in 1968. It started out as classified ads--my parents [Jim and Katie Heth] went around to all these places and got people's ads off bulletin boards, and they called them and asked them if they'd like to put an ad in this newspaper. The deal was if you sold it you'd pay a commission on the item. So my brother would call them later and say. 'I'm calling about that car you have for sale. Oh, you sold it? OK, well, this is Jeff from the People's Press ...' And Bruce Bratton, he grew up with the newspaper. We met him because he was running an ad for lion manure. My father was like, "Who's this guy who's running a commission ad for lion manure in trade for Barbie dolls?" Three or four years later, they turned it into a paper with news in it. Was that my father's intention from the beginning? To rule the world? Yeah. He was for everything that was against the government, it didn't matter what it was. He picked the underdog's side at all turns. And he liked people that were completely different, he fit in Santa Cruz so well that way. If you came in looking scruffy but had some eloquence in your speech, my father would take you in, tell your story to the world and rent you the back bedroom. Bruce Bratton: The [People's] Buy and Sell Press, Jim Heth and his wife owned it. He bought a web press and kept it in his garage. It was about eight feet high and wide as a car, and he'd be all over that thing and ink everywhere ... it was like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. We had the teletype machine in the bathtub in the house. Rick Gladstone: There was always a constant, ongoing group dialogue about what we were doing--that was part of the zeitgeist. We were very committed to that kind of format, we saw that that was the spirit that prevailed in other alternative press journals around.

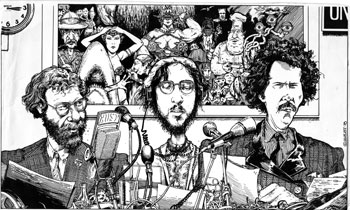

Manufacturing Dissent: After starting up in the late '60s, the People's Buy and Sell Press briefly provided an alternative and far more left-wing daily-newspaper viewpoint for Santa Cruz readers in the early '70s.

1970-1973

Jenny Heth: By the time we hit Soquel, the People's Press was a real newspaper, I was about 12 or 13 years old, the print shop was in the garage, the newspaper offices were in the living room, and at the same time my father and his brother started a live theater group down the street. In the living room was the used clothing store called "Refried Jeans" that my mother and sister started. In the bathroom was the old typesetting equipment in the tub. Our house was basically only two rooms--the rest was some kind of commerce thing. It became more of a formal publication when my father got legally adjudicated. He rented an office right across from the Sentinel, that's when things started off for People's Press. Dig this--my father, he has this big sign painted that said, "Our Ads Work Better." And everything was a little cheaper than the Sentinel. Futzie Nutzle: People on the staff [of Sundaze] then were pretty open, it was more like the second floor office with the windows open and a six pack of beer, typewriters going, and a lot of pushpins and wind blowing papers off bulletin boards--sort of a Raymond Chandler kind of office, that kind of a scene. Michael S. Gant: [Sundãz!] covered local politics; a big part of its interest was environmental and anti-overdevelopment issues--lighthouse field, the North Coast. It was not a hierarchical organization by any means. It was the early '70s, kind of like the early Berkeley Barb sort of thinking, including, you know, some wild graphics, turning loose pages over to cartoonists and so on, but not for panels, more for just psychedelia. We ran poetry--no one runs poetry anymore. Poets are too much trouble. But back then it was poetry, it was art, it was cartoonists. It had a loose-limbed sense of humor, it was a forum for a lot of people to write columns, turn in art, and there weren't many guidelines; it was a lot of fun. There weren't templates, and plus, that was the graphic movement of the time--if you look at the psychedelic art posters coming out of San Francisco, there was a spacey art movement in the '60s that was extremely fluid and experimental. Because people were stoned. Geoffrey Dunn: Sundãz! published my first article right before my 19th birthday. I just submitted a piece, they accepted it, and I went and got it from the stand and there it was on the front page. All my primary stuff has been for alternative press. Just the lively street nature of it was incredibly attractive, once a week these publications would suddenly materialize on the street. There was this vitality to the whole process, this magic and excitement. Tim Eagan: I remember fondly being in the Sundãz! office, you had windows that you could look out and see everything. So if you saw somebody who deserved it, there was the office duck call, it was just sort of idle fun, for people who deserved it. Peggy Townsend got her share of duck calls, walking past from the Sentinel to downtown. There was much more, we were out drinking together at the bars after deadlines on Thursdays or Friday, the so-called newspaper people who had nothing to do, that was their job, making $40 dollars a week working at Sundãz! and then blow it on beer and raucous conversation. Stephen Kessler: I started writing some articles for Sundãz!; they had a poetry page and I started sending in poetry. For a while I was their poetry editor. I remember coming back from Europe in 1976 and discovered that the Sundãz! had disappeared and the Santa Cruz Independent had taken its place.

1973-1979

Buz Bezore: A new publication started up, Jay Shore's Santa Cruz Times, which was a general interest alternative publication. It had news, entertainment and sort of a leftist bent. That lasted just a very short time, until he decided to take his center section called Good Times and have that as a stand-alone. I was there from day one, I was their music editor. Jay Shore was one of the most evil people to walk that planet, except he would always have one or two people that he treated well. He was a wannabe musician, and since I was the music guy, he always treated me fine. He wanted to go drink and be my friend, but he was an unlikable guy. I ended up quitting finally because more than once I would go into work and there would be two different people crying for two different reasons at the same time, literally crying for something that Jay had said or done. So I sort of developed an Auschwitz Syndrome where I had survived, but had seen all this collateral damage around me, and I couldn't take it anymore. So I quit and went over to another paper called People's [Buy and Sell] Press, run right across the street from the Sentinel. The People's Press was run by another madman, Jim Heth, who had a grandiose dream of becoming a supervisor, so he used the paper as his platform, and I ended up being their arts and entertainment guy. The news guy was Kelly Garrett. Jenny Heth: My father is my hero. He's the one that taught me to tell people to fuck off. He's the reason I managed to start my own business at twenty years old as a high school drop-out, because of his world view. I learned how to do ad layout when I was 13. After [People's Press] went daily and that didn't work, my parents were broke. They moved the office back to Church Street and turned the paper back into a classified ad rag. The Morning Star put them out of business essentially. It was too big a bite and they went into great debt to do it. So that's what killed it--they spread everything too thin. Tim Eagan: Sundãz! folded, and shortly thereafter, Richard Cole and I decided to fill the hole. He was the editor and I was the so-called publisher of the Independent. Our office was at Church and Pacific, that was a more businesslike operation, it had a real staff, and it ran into right in the middle of a supervisorial election. It was a time that the Board of Supervisors had a conservative side, and then had a more liberal side, and then the third seat, the balance seat. I genuinely feel like we had an effect on the election that year, the two candidates we endorsed both won, and we congratulated ourselves for having an effect on the system. It sort of felt like we were in the middle of something ... whether we really were or not. Neil Smyth: Come to find out [the Independent] was a collective newspaper and I had a real attraction to that. Decisions were made by votes; that often involved really long meetings. It didn't always work, but we tried to do things by consensus. Michael S. Gant: I remember going to a hell of a lot of meetings about it, people were really into meetings--collective meetings--as a way of running things. You've got to remember that in those days everybody hated the Sentinel, they thought it was just terrible, and there was a concerted effort to form a collective newspaper to keep some kind of left political voice. Tim Eagan: They did some good muckraking, Richard Cole did the story on the secret plans for a nuclear power plant in Davenport. He blew the lid off it, it was a great story, somehow he had gotten somebody to give him this information in confidence, and PG&E was really embarrassed. After that news got out they put the kibosh on it. Buz Bezore: Richard was very sharp--I don't like him, but he was good. Tim Eagan: I ran for district attorney when I came here, and the Independent endorsed me, much to the chagrin of Richard Cole. He took his endorsements seriously, as he should, but they endorsed me for DA, so that was my little victory. Neil Smyth: AWEST and Tim Eagan, I thought that was a real strength of the Independent. The graphics and the comedy. "The Duck Brothers," "Subconscious Comics." You talk to people who have lived in Santa Cruz for a long time, they'll go, "Oh yeah!" Buz Bezore: We were also known for our April Fool's issue. We had one called Goon Times, and we had completely parodied the look and feel and the tone of Good Times. The next year we did a variation on the Weekly World News, and the headline was, "Welfare Mother Eats Child," and one on how the Good Times porno ring was broken up. One of the stories was that kidnapped babies were on little treadmills keeping the rides going at the Boardwalk. We were notorious for doing this issue, in fact all of our lefty friends came in and screamed at us and yelled at us and said all this horrible stuff, that we had betrayed the leftist cause by making fun of all this stuff we defended. So I got to see the left in the least humorous light. I always said I was a "Maverick Libertarian" after that, because I didn't want to be associated with these humorless dolts. Dan Pulcrano: The Independent is where I met Buz Bezore and Michael Gant, and Neil Smyth was there--the usual cast of characters. That kind of thread has been running through numerous papers through the years. Santa Cruz was a fun place in the '70s--there was music and people were dancing in the streets in front of the Cooper House. It really was a special place. Here I was 18, and I just couldn't believe life was like that. I'd go to work at the Independent, and guys like Cornelius Bumpus--who just died, he was in Steely Dan and the Doobie Brothers--were playing right there in public for free. And then there were all these artists and writers: Ken Kesey, Albert Hoffman, Allen Ginsberg, Tim Leary--they all came to UCSC the month I got to campus. I was like, "Wow, this is quite a place." Michael S. Gant: It was as much a cause as a job. We were pretty tight knit; it's not like we were living on a commune together, but we all spent a lot of time arguing and working together, and socializing together, drinking down at the Catalyst and over at the Cooper House bar, which was a great bar, all the politicians would roll in on a Friday night and all the people from the papers. I think the Good Times was up and rolling certainly at that point. Then there was this People's Press, and City on a Hill used to be a very active paper with a downtown presence. Pretty much everybody knew everybody. I knew people who worked at the Good Times, we all played softball together--we had a media softball league, everybody did that, that included Sentinel people too, because they started getting some younger people. Bruce Bratton: I got involved with the Independent just because I knew everybody. We all knew each other, we all hung out together, from all the papers, at the old Catalyst on Friday. Even the Sentinel people. Besides that, you'd work for one paper and then you'd quit and go work for another paper. In those days--and this is really serious--if a newspaper was late in being delivered, you'd say 'Ahhh, I bet the Phoenix folded.' Or 'Good Times, they must've folded.' It was that iffy, all of the papers. Neil Smyth: A lot of times the Independent would have a lot of stories against rapid growth, and that inherently was against what most businesspeople wanted. I remember one of the biggest dilemmas for the paper was you'd have these stories that business owners didn't like, and then you'd have people going out to sell them ads. It was really difficult to get businesses to run ads, because they didn't want to support something that was against their interest. John Keith: I think it's true that everybody who worked on that paper bought into a more or less lefty political stance. That was a real difference and I think we kind of all prided ourselves on that, we've got a real paper and we address real issues. The Good Times in those days did nothing controversial at all, so that was a natural vehicle for advertising, because you're not going to alienate anybody. Buz Bezore: We were all working for $50 a week; we were a collective. We had some impact on the town, both the arts and the news, and then somebody wanted to buy us. There was this guy named Jerry Fuchs who had a group of papers he owned back East. So we had these big knockdown, drag-out meetings about "Should we sell?" because if we did, we'd all be making a livable wage. And so it broke down between the communists and the capitalists, that's what we called ourselves. It was finally decided that we were gonna sell, but Richard Cole pulled out some contract to show that he was the real boss and we were all slaves and called the deal off. A bunch of people were consequently fired by him, and I was one of those people. We were unfriendly I think for a variety of reasons, but I think one reason was that he was power-mad by that time. So they called the deal off, but what happened was this Jerry Fuchs got back in touch with me, he still wanted to buy the paper, and would I help him if he bought it? They used this guy Charlie Leddon as a front guy to buy the paper and not let Cole know it was Fuchs. So here's this guy Leddon--who was also [carrying on with] Fuchs' wife at the time, which led to big problems later on--and Richard Cole finally sold the paper to this guy Charlie Leddon, and was supposed to take the money and divide it among all the people who were still working there. I'm across the street drinking, and Charlie Leddon signed the papers and they come across the street to say that the paper's been sold. So I get to walk across the street--one of my happiest moments ever-- and I walk into Cole's office and Cole says, "What are you doing in here?" I said, "You're sitting in my seat." And he said, "What do you mean?" And I said, "You're fired." It was wonderful--the only person who I ever fired in my entire life. Tim Eagan: Cole sold the Independent and went to Brazil with most of the money. Fuchs was the guy from Gilroy who wrote a column called, "Nobody Asked Me, But ..." which just about sums it up. He didn't mess with the paper politically, but his opinions came through in his column. Dan Pulcrano: Jerry Fuchs didn't really understand alternative journalism. Jerry tried, but he didn't know what to do with it. Through the "greater sucker theory," he sold it to these real estate people from the San Lorenzo Valley, Polly and Mike Doyle, who destroyed what was left of it.

1979-1981

Geoffrey Dunn: The Phoenix was definitely more left-wing focused, and it was definitely more serious with a high emphasis on politics; that one was run just entirely as a collective. Neil Smyth: For the Phoenix, selling ads was almost impossible. I remember [my wife] Maria [Castro] being one of the main people that sold ads, and it was really difficult. Sometimes a business would do a tiny ad just to not have them bug them anymore. They didn't do it because they thought it was going to help their business; they were just supporting something. We did political feature articles and it was a completely partisan press, and was therefore kind of boring, frankly. So that's probably part of the reason we drifted away. Buz Bezore: Joseph Grassadonia and Grady Morleand had this publication called Center Stage about theater, and they wanted to start another publication called Santa Cruz Weekly. They brought me in to start it, using basically the same formula I had been doing my entire life, which was essentially, news, humor, entertainment, food and stories about people in our town. But these guys were so crazy, and they were ruining the paper. Dan Pulcrano: Joseph didn't know what to do with that cast of characters, these were basically terrorists with typewriters; he couldn't really keep them in control either, so it spun out of control. Buz Bezore: So about five of us went to see their bookkeeper, because we were trying to figure out how this thing was going to last, so the accountant goes, "Why don't you just take over the paper?" And we go, "Can we do that?" And they go, "Yeah!" It was so underhanded! So we said all right, so we concoct this giant conspiracy to offer to buy the paper, and their accountants are telling them, "Yeah, it's a good price, take it!" And the accountants are advising us, too. We finally got them weaseled down to some acceptable price, and the accountant was going to put up the money for it! So he drew up all these papers, and I had never read a contract in my life, and I said. "I trust you guys." So the paper is bought from these guys, we take it over, we had just got Bruce Bratton to quit Good Times to write for us, and we were going to be the king of the village. On the first day of work, I walked in and I go, "Where is everybody?" And the account said, "We fired them all." And I said, "What?" And he said, "We own the paper. You didn't read the contract, did you? We're losing money and we're going to turn it into a Real Estate paper." It was so surreal! Dan Pulcrano: [Grassadonia] sold to an accountant, Bob Davidson, who hired me a few days later to run it and then fired me three weeks later. There was a rebellion from the former staff, and I was basically editing under fire--I had to put together a staff overnight and fend off death threats. I think the main reason I was fired was I was too independent and [Bob] wanted an editor he thought he could control. I was kind of a mixed breed too, people didn't understand me because I was a journalist and also a businessman. Buz Bezore: We, in the meantime, had walked across the street and decided, "Oh what the hey, let's start another paper!" We had Bratton, we had the arts crew, we had the sales team, all of us were there, so we just decided to go ahead and do it. We called ourselves the "ex-press," because we had all been fired.

1981-1986

Geoffrey Dunn: Buz Bezore and company put together the Santa Cruz Express, and I was a little pissed off about it coming into being, quite frankly. It was a blend of the cultural stuff of Good Times and the politics in the Phoenix. I think it was one of the great moments in Santa Cruz alternative journalism--it had an incredible crew of writers, photographers and artists. When it was really cooking, it was one of the great moments in the history of alternative journalism in the country. Buz Bezore: The Phoenix and the Express were sort of antagonistic toward each other because we thought they were humorless, and they thought that we were too moderate. When the Phoenix folded, Roz [Spafford] worked with us after that--we had so many columnists, there would be a news story, a cover story, and maybe five or six columnists writing about issues germane to the town or the nation at the time. Our joke was, we're a local paper, and we cover everything from Davenport to Rio Del Mar and Nicaragua. Tim Eagan: At the Express, Buz Bezore's sensibility was kind of a post-Hustler take on things, with similar elements as the Independent seen through a different lens. Geoffrey Dunn: Buz Bezore, I think he was an incredible editor, he refused to be politically correct in a politically correct town, and he was willing to take chances and willing to take chances with young writers. He trusted the artistic instincts of his writers and artists; rather than trying to confine them, he nourished them. I think a lot of editors think their job is to reign their writers in, but he just let us go. Rob Breszny came out of that, Christina Waters was at her peak then, Michael Gant was writing regularly then; it was a great publication. Bruce Bratton: That's when I could start getting involved with issues. We had a drought, and I took on the Boardwalk back then when they opened up their log ride in the middle of this drought. We got nice and fat then, lots of pages. A whole lot of good people came together at the right time, and we had more of a business sense than we ever had before, but not enough. Not enough attention was paid to ad sales and editorial expense. We should have had an accountant, because there weren't any of us who were that good at it, or could command that much power to say no, you can't do that. And we used to have enormous parties--all from trade accounts--big, wonderful catered parties. Buz Bezore: Then at some point we got in big trouble with the tax people, it sort of cleaved the organization in two again. Stephen Kessler: In the spring of 1986, just as Express was celebrating its fifth anniversary, there was some kind of crisis; I worked from home, so I didn't understand what was going on. I have a very specific memory for what happened, but it is memory and memories are often in dispute. The IRS in about '85 started sending notices to the Express, presumably to Buz Bezore--and this was another perverse part of his genius, was that although he was running the paper, he was not assuming responsibility for running the paper. They had been in arrears of their payroll taxes, not been paying any payroll taxes on their employees from the time they started. So I was recruited basically to overthrow the management of the Express, and it was like having to murder your father, because Buz was the person who got me into all this stuff in the first place, and I really loved him as an editor. But there was a level of irresponsibility going on in taking the paper into a terminal crisis, and something had to be done. So with the board of directors, we basically fired Buz and Christina quit. And immediately they started their own paper, called Taste. I, much to my chagrin, was forced to step in with no experience in this particular kind of editing to the position of editor of the Express. This was in '86. Michael Gant was basically my training wheels, I had never edited anything as complicated as a newspaper. I stepped in there and tried to keep the paper alive. But in the meantime I had people step in and look at the books and evaluate our business situation, and it was grim. It became clear that without a massive infusion of capital, there was no way we were going to keep the Express alive, especially with Buz Bezore and Christina Waters out in the community starting their own paper and telling advertisers in town that the Express was on its way down. That's when the bad blood started to flow, we would see each other on the street and our adrenaline would just shoot through the roof. Downtown, you inevitably walked into people you knew. And when you were involved in almost a battle to the death over the future of alternative journalism in Santa Cruz, and your closest enemies were also your former colleges and comrades, it got very Dostoevskyan, it was very emotionally volatile. Eventually I came to my senses and realized that this was a losing proposition. So we folded up the paper. It was a real tearjerker.

1986-1989

Stephen Kessler: A lot of us who worked at the Express, we were homeless, grief-stricken and without a newspaper. We had spent, most of us, at least 10 years working for these oddball weeklies in Santa Cruz. People like Gant and Eagan, later me, Bob Johnson, Bruce Bratton--who at that time was also without a newspaper, everybody wanted to have an alternative newspaper. And, fool that I am, I thought OK, well, the Express stayed alive for five years in spite of the fact that it had no management. What if a newspaper actually did have a management with some kind of money in it, with some kind of rational business strategy? So we raised $100,000, and we started the Sun, partly in homage to the Sundãz!, which was our progenitor back in the '70s. Bruce Bratton: What happened after the Express folded? Loneliness. Stephen Kessler started the Sun, and almost everybody but me got in, they wouldn't hire me. It was Kessler, Gant and Geoff Dunn, he was more active with the Sun. So I just didn't have anything. And then later Geoff started Santa Cruz Magazine, and then I did the same kind of column. My column lots of times has been down, one year, two years, and then something would change and someone would say "Hey, let's get Bratton." Tai Moses: The Sun was I think only a couple of months old, and I responded to an ad for an intern on the back page. So he hired me and I think that was my first experience in journalism. Stephen and I have a joke that he ruined me for any other job, because he let me write about whatever I wanted to write about. Literally. I wrote "A Tale of Two Dumps," a story about trash. I got to express myself in a creative way, which is very different than when you start out as a reporter for a mainstream publication. You learn to be a reporter and not a storyteller. Alternative papers are all about storytelling. I still look at my clips and just get so nostalgic--it's been so long that I've been able to do that kind of writing. There's really not much of a place for it anymore. Stephen Kessler: We had a hell of a time, we reminisce about this period when the Sun existed because we had so much fun. We actually wrote editorials, we actually took positions on things--six of us would get together first thing Monday morning, we'd brainstorm as to what we should editorialize about, and based on that, I would write the editorial. I thought I had the best job in town. Tai Moses: Editorials are something that, sadly, very few alternative weeklies have any more. It had a definite voice, it had opinions and it took positions--it played a really important role in the community that way. Stephen Kessler: The Good Times at that time, their motto was "Lighter Than Air," that was literally on their masthead. It was literally the airhead entertainment weekly, no substance at all. The Sun was truly an alternative newspaper; we joined AAN, we went to the conventions. And I tried to call forth all my entrepreneurial instincts in order to keep this newspaper alive. I worked six days a week, gave it all I had, but it just wasn't enough. Tim Eagan: I mark the earthquake as the end of that era, it wiped out the Sun. Stephen Kessler: They set up tents [for the businesses downtown], and that was it, like the hand of God coming down and swatting me, saying, "Wise up, fucker, this is not the way to spend your life. You're about to just be sucked into complete financial disaster if you try to continue this."

1990-1994

Geoffrey Dunn: The Sun wasn't quite as irreverent as the Express nor as dynamic I would say, but a really good paper. And then after the earthquake hit and wiped it out, I kind of felt obliged to pick up the gauntlet. It was like the whole of alternative journalism was going to die. Santa Cruz Magazine lasted from May of '90, the last issue was April of 1994, so it lasted four years. I was the original publisher and editor along with Rick Hildreth. Contentwise, it fell between the Express and the Sun, but after the earthquake, the economy just wouldn't support a weekly publication for a while. I honestly always saw the magazine as just a bridge, I just didn't want to lose any money on it, the two predecessors the Express and Sun had really lost a lot of money and left investors holding the bag. We basically ran at a break-even point for four years. That was kinda the commitment. When Metro came along--I had always been writing for Metro Silicon Valley, and Dan and I just came to the agreement that we would close Santa Cruz Magazine down. Dan Pulcrano: I started Los Gatos Weekly when I was 23 and then Metro three years later. When we started Metro Santa Cruz in '94, it was kind of like coming full circle. It wasn't as if a San Jose publisher had started a Santa Cruz paper--for me, it was as if Santa Cruz journalism had come over to the valley and then returned. The Metro staff for years was all Santa Cruz grads: myself, Michael Gant, Richard von Busack, Sharan Street and Richard Curtis, who was Metro's first art director. So I'd say Metro is more influenced by the Santa Cruz journalism tradition than Santa Cruz has ever been contaminated by any valley ethics.

Cast of Characters In Santa Cruz alternative journalism, the players get around. Here's a list of the voices in this article and the rags with which they were associated.

Buz Bezore: Santa Cruz Sentinel, People's Buy and Sell Press, Santa Cruz Times, Good Times, Santa Cruz Weekly, Santa Cruz Independent, Santa Cruz Express, Taste, Metro Santa Cruz

|

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

From the May 5-12, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)