![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Santa Cruz Week | SantaCruz Home | Archives ]

10 Years of Troublemaking

Looking back at some of Metro Santa Cruz's best and ballsiest moments over the last decade

Editor's Note: Our original idea for this 10th anniversary issue of Metro Santa Cruz was to focus solely on the upstanding (and sometimes careening wildly) tradition of independent Santa Cruz journalism that led to the founding of this paper in the first place. That we did, but when we were done tracing our roots, we started thinking it might be fun to look back at how Metro Santa Cruz has continued down the path that early alternative papers blazed in this town, by reprinting a handful of the most lauded, most shocking and most entertaining pieces we've run over the years. Keep in mind that these are only short excerpts from each of the ten stories we chose. And even though you didn't ask, no, it wasn't easy to pick 'em. There's been a lot of great reporting, writing, philosophizing, goat-getting and general troublemaking in these pages in the last 10 years. But we did try to cover a fair amount of ground, not just chronologically, but also in terms of subject matter and technique--from exposé to arts writing to analysis, from in-depth and offbeat investigations to personal stories to political rallying cries to movie and music coverage. And to think we haven't even hit puberty yet.

Blood Sport

Participants in the illegal pastime of cockfighting are willing to risk property and freedom in pursuit of their passion

By Michael Mechanic

At 11:30am on Feb. 26, state humane investigators and city police officers swooped in on a small house at the end of Second Street in Watsonville, driven by a tip that a Sunday morning cockfight was in progress. It was a high-profile bust, with color photos splashed across the front page of local dailies. Seized were 75 roosters, illegal fighting implements--in this case, the "short knives" popular with Mexican cockfighters--and hypodermics, which are used for the birds' health care or to inject birds with stimulants before a fight. Also seized was the owner of the house, a man named Olegario Perez Hurtado.

In many ways, Hurtado, 45, was a typical low-level cockfighter. Other than his passion for roosters, he stayed out of trouble. He has a wife, five kids and a decent job as a laborer at Wrigley's gum factory in Santa Cruz. But his illegal hobby ultimately turned his life upside-down and resulted in a felony conviction for animal cruelty.

Slapped with 30 days in jail, three years' probation and a $1,447.50 in fines and restitution, Hurtado now keeps away from roosters, unlike the estimated thousands of other Californians living in semirural and rural areas who raise anywhere from a handful to hundreds of gamecocks. Those who raise and fight the birds illegally here, or even take them to states where cockfighting is legal, are willing to risk fines, incarceration and--perhaps worse in their view--the loss of their prized birds.

Authorities say they've seen grown men weep when their roosters were confiscated. "The average cockfighter is probably not a bad person," says Mike Frazer, an ex-San Jose cop and investigator with the Santa Clara Valley Humane Society. "They don't do it to cause pain and suffering. It's amusement. The birds are competing for them. People who breed birds are very proud--it's like mechanics at a drag race. They don't want to see their birds hurt; they want to see them win. But, in fact, it's illegal, and we have to enforce the law."

And happen frequently it does--practically every weekend between November and August (when the birds begin molting). A drive along Watsonville's back roads reveals scores of "teepees," upside-down wooden V-shaped shelters, each housing a single gamecock. Each rooster s tethered near its teepee because the birds would battle if left to their own affairs. "It's so prevalent in Watsonville, I couldn't put a number on it," says Skip Prigee, until recently a state humane investigator with the Santa Cruz County SPCA.

Cockfighting is a very bloody pastime. The handlers attach razor-sharp knives to the roosters' ankles or spurs. The rules of engagement often depend on the weapon, and the weapon used depends on who's fighting. Mexicans favor "short knives," an inch or two long. Filipinos prefer 3- to 5-inch "long knives," while Anglo cockfighters mainly use "gaffs" or "bayonets," sharp curved spikes 1 to 3 inches in length.

Handlers crouch in a small ring, or "pit," holding their birds a short distance apart on either side of the "scratch line." The referee calls, "Pit 'em!" and these birds fly at each other, striking out violently with their legs--knives gouging and slashing. If the birds hang up on each others' knives, the referee yells, "Handle!" and the handlers separate the combatants. The fight continues until one bird is dead or quits, while greenbacks clenched in the hands of onlookers multiply or diminish according to the outcome.

To many sensibilities, the bloody use of these birds for amusement and betting is abhorrent. "It's a very violent manipulation and exploitation of the animals," says Kat Brown, director of operations at the Santa Cruz County SPCA, reflecting a view held by many animal lovers.

Cockers, who also consider themselves animal lovers, see their pastime in quite a different light. Breeders point to how well they care for their chickens outside the pit.

Indeed, compared with the commercial poultry industry, which mass produces plump chickens for the table, game fowl are treated like royal soldiers. The birds get fancy feed, far more space than commercially grown chickens and superior health care. Hens don't fight and males that survive several pits are often retired as brood cocks--breeders, that is.

In other words, cockers say, eatin' chickens don't have a prayer, whereas gamecocks live better, fight according to their instincts and get a shot at survival. "These guys, every one of them would fight to the death," says Manuel Costa, indicating his birds.

Costa is both an avid breeder and president of the APG (Association for the Preservation of Gamefowl), a statewide organization of breeders that lobbies for changes in the laws, stages fowl shows and claims, at least officially, not to condone cockfighting. "That bird does not know any better," Costa says. "He's been bred [to fight]. Now isn't it better to give him the chance to wine five or six fights and then be a brood cock or is it better if Animal Control takes that bird and he ain't got a chance? They call it euthanasia; it sounds so nice. But death is death. I don't care how you accomplish it."

Big Problems

Ron Nance spent his inheritance to become a member of the elite club of men with humongous penises. But complications from the so-called 'perfectly safe' penile enlargement surgery have left him--and many others--shriveled, shamed and unable to perform sexually.

By Ami Chen Mills

"I live in a place where God comes for vacation," says Ron Nance, gesturing toward the cliff edge just feet from his plastic dock chair. Out past the broken promontory, the cool, sapphire-blue waters of Monterey Bay stretch toward Moss Landing, and the hushed rhythm of breaking waves rises like a lullaby from New Brighton Beach below.

From Ron's front yard--studded with Monterey pine and eucalyptus trees--you can see forever. But not if you're Ron Nance. "I've almost stepped off this cliff so many times," he says, tears falling rapidly from behind his impenetrable shades. "Look at this. It's so romantic--and my intimacy has been robbed from me."

A year and a half ago, Ron was 46, a carpenter with a simple life. He'd just inherited 30 grand, had few debts and a new girlfriend.

"We were consumed," he says. "Mary" took him to his first opera. He took her on her first motorcycle ride. They made love in his former Felton home.

Ron says, "It was wonderful. But I thought if I was just a little bit bigger, the sex would keep getting better."

After nearly a year, the passion cooled. "She seemed to outgrow me. We started to drift ..."

That's when Ron saw the ad in the San Jose Mercury News. In bold letters the ad proclaimed: "For Men Only: Be All the Man You Want to Be!" It was one in a $200,000-a-month campaign waged at the time by urologist Melvyn Rosenstein, a man who traded his upright urological practices for a lucrative stake in the booming penile-enlargement industry. Today Rosenstein, one of the first and most famous penile enlargement surgeons, faces the end of his career. As of Jan. 25, Rosenstein's medical license was restricted to protect "public health and safety" pending a medical board hearing. The celebrated surgeon of schlongs faces permanent suspension from the California Medical Board based on complaints from patients--including Ron Nance--whose enlargements have gone wrong.

Rosenstein's method involves severing the suspensory ligament which holds some of the penile shaft inside the abdomen. The shaft ostensibly drops, adding length, and body fat retrieved elsewhere is injected into the penis to increase girth.

It all sounded good to Ron Nance. With a few grand in the bank and a girlfriend who seemed to be slipping away, Ron decided, "I'm going to do something for Ron."

The procedure took one hour. There was a recovery period of one hour. Then Ron was shipped home. Still dazed, Ron assumed he had a bigger, better penis. The Rosenstein Medical Group was $5,900 richer--a drop in the bucket for a business that grosses upward of an estimated $13 million annually.

Back in Felton, as medication wore off, the nightmare began. Nance is no stranger to pain. A carpenter and an active, middle-aged man, Ron has suffered a ruptured disc, fractured jaw, broken collarbone, ankle and nose, cracked skull and split sternum. "I had a long love affair with pain," he says. The pain he suffered after his enlargement surgery, however, was worse than anything he'd experienced. "That wasn't even the first step in this ladder."

According to Ron, incision areas became infected. His foreskin clamped shut because of swelling. He couldn't urinate. Following Rosenstein's "helpful post-operative hints," which advise against calling another doctor or hospital, Ron called the Rosenstein clinic and spoke with Dr. Rosenstein, who told him to squeeze his penis to force discharge out and put a bandage on it. "Your member is dying and screaming, 'Don't touch me!' and you're supposed to squeeze it with all your strength," Ron moans.

Although Dr. Rosenstein wrote on Nov. 28 that Ron was "markedly improved," Ron Nance would fly back to L.A. for repair work four more times. His penis was now shorter than before he had the procedure. By Jan. 30, two months after the first operation, he was unable to have an erection. He was told to buy weights to hang from his penis to correct bending. He was sold a bag of needles to shoot hormones into his penis to achieve an erection.

With a smaller, impotent penis, now disfigured and still sometimes in pain, Ron Nance was a wreck. Ashamed to admit he'd squandered his inheritance on a vanity operation, he avoided friends. His family kept an awkward distance. Ron became a recluse. Still unable to perform sexually, Ron told Rosenstein in February 1995 that he was out of money.

Sitting on the cliff edge near the stone cabin where he moved last year, Ron weeps. But a white-hot anger rises through his sobs. "I try to be real selective about the piles of shit I step in. But sometimes you don't know what you're getting into. He always said he was going to stand by me. I feel like a woman must feel when somebody's raped her. I feel real dirty." Sobs overcome him. There is only the sound of Ron crying and surf pounding the beach below. It's the background music of his recent life.

(To read the full article, click here.)

Dec. 24, 1997

Grier Window

'Jackie Brown' is a talky Tarantino love letter to famed blaxploitation icon of the 1970s Pam Grier

By Richard von Busack

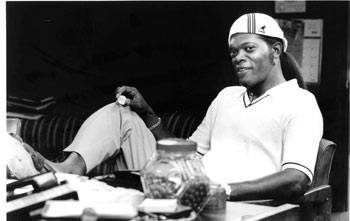

I watched a reporter from Black Diaspora magazine get right into Samuel L. Jackson's famous face over his use of the word "nigger" in the new Quentin Tarantino movie, Jackie Brown. Jackson--as fiery a rageball as the screen offers today--lost his temper. "Why are you so offended?" he asked, almost shouting. "In the script, that word is used as a term of endearment as often as it is derogatory. Where did you grow up?"

Trinidad, she told him. And where she came from, they don't use that word. It's an insult. How was she to recommend a movie if it insulted her people?

"I grew up in Tennessee, where I heard that word yelled at me from off of buses," Jackson shot back. "Believe me, if I'm not offended by it, why should you be?"

"Because people in the audience snickered whenever they heard it!" the reporter answered.

There were a few other critics at the press table. Jackson looked around for support--as if white liberals like me were going to say they thought the word "nigger" was good fun! And Jackson does use the word quite a bit in Jackie Brown. He admitted, "I use it four times in one sentence."

A little later, after he calmed down, I changed the subject and asked Jackson what his methods are for projecting menace. He demonstrated.

"I just get a look on my face like my mother used to give me when she wanted me to shut up, but she didn't want to say so out loud," Jackson explained. "Sometimes I look at a person and think, I'm going to kill you."

Jackson demonstrated the correct posture. He leaned forward, raising his shoulders up and crossing his arms tightly, high up in front of the breastbone, fists tucked inside elbows, as if his hands were cold. He glared at me frostily. I was impressed; he was just as scary in person as he is on the big screen.

"Anyone here laugh when they heard that word?" Jackson asked.

"No, I don't use that word, and I don't snicker when I hear it," I replied, which was a half-truth. Later on, I remembered someone who could make me laugh when I heard it.

(To read the full article, click here.)

April 1, 1998

High on Life

Is Akima the miracle drug of the 21st century? New research reveals that a Brazilian herb has the power to elevate users to new heights--without side effects

By Barry Friedman

The article you are now reading is a special one, indeed the most unusual ever to appear in any publication. A section of this story has been coated with an odorless, tasteless drug. Its name is Akima (Yobumji for "Life") and when consumed makes the user feel like he or she is 10,000 feet tall.

Akima is found but one place in the world: a remote and sparsely inhabited area of the vast Brazilian rain forest known as Marapampa district. There are no roads here; no ramshackle towns slashed out of the jungle; no laws--some might even say no God.

For the few native people, it is still the Stone Age, and they invoke the names of ancient spirits to protect themselves from the fearsome demons they are convinced lurk unseen on Earth. Their sacrament is Akima (pronounced "ah-key-mah"), which literally translates to "Cloudseeker."

Produced from the leaves of a very rare plant that grows only in tiny clusters in this savage land, the natives believe that the illusion of tremendous height created by the drug allows them to tower above the trees out of the reach of their enemies.

The drug was first mentioned in a Newsweek article that appeared almost 20 years ago. An international team of archaeologists had penetrated the previously unexplored area to search for what aerial photographs suggested might possibly be a highly unusual and complex network of man-made canals.

Eighteen years passed, and despite many inquiries and voracious reading, I encountered no further reference to the drug. The break came two years ago. A friend of a friend of a friend was joining a Brazilian surveying team in a supervisory capacity. Calls were made, a dialogue established. Yes, he would be going to the Marapampa district.

I told him the little I knew about Akima. He was equally intrigued and vowed to obtain a quantity if at all possible. Somehow he did just that and, by means I have pledged not to reveal, delivered it into my hands.

I am now delivering it into yours. Each and every copy of this publication has a small area of newsprint that has been coated with the recommended liquid dosage of Akima, thanks to the untiring efforts of my colleagues: Ryan Matthews, Joel Burstein, Aaron Jacob and Rudy Adler. There is no doubt in any of our minds that Akima is a miracle drug that makes such hallucinogens as LSD-25 seem like nothing more than mad scientific quackery.

Akima is most certainly a drug--and I do not advocate the assimilation of any narcotic without a thorough understanding of the possible consequences. It is with this in mind that Metro Santa Cruz commissioned a full-scale analysis of Akima by the world's most prestigious pharmaceutical research laboratory, Greenchem of Scotts Valley.

I urge you to examine scrupulously the companion lab report published in conjunction with this article and carefully weigh its conclusions. We are completely satisfied. Our personal experience is that Akima produces an overwhelming feeling of serene bliss triggered by a profound sense of unparalleled height.

There are no addictive properties, no negative aftereffects. The drug is simply too new to legislate, and at this time, it is highly unlikely that the FDA is even aware of its existence.

Which brings us inexorably to you. Is Akima for you? It is a decision that you and you alone must make now. The drug rapidly loses its potency when exposed to air and will totally dissipate within one, possibly two days following publication.

If your decision is positive, carefully cut out the blank circular area on the previous page, crumple it into a compact ball, and let it dissolve into your mouth for a period of time not fewer than three minutes. It is not at all necessary to actually chew the paper; the Akima will be quickly absorbed into the bloodstream by osmosis through the soft tissue walls of the palate.

The choice is yours.

(To read the full article, click here.)

C and Be Seen

There could be worse things than having a chronic, life-threatening, stigmatizing virus. No, really.

By Kelly Luker

Let's just get this out of the way right now. Maybe Bill Clinton didn't inhale back in the '60s, but I did. And snorted and drank to excess. And injected. A lot. That fun little decade gave me enough material to pen overwrought confessionals for a lifetime, entertain my friends in rehab and remind me that I can visit hell on earth anytime I want.

This is not the beginning of a tell-all memoir, but merely a bit of history that is relevant to a here-and-now situation that found its roots in that decade.

It appears that along with vintage Fillmore posters and bad memories, I and about 4 million other people in America have another token from that groovy era: hepatitis C.

"The Silent Killer," journalists and health professionals call this virus that can slowly destroy the liver. "The Shadow Epidemic," it's been labeled, because of the 4 million folks in the United States who have hepatitis C, according to the Centers for Disease Control, 3 million don't know it. Maybe our collective ignorance can be chalked up to a disease that has garnered minuscule media coverage, at least compared to AIDS, cancer or even Legionnaires' disease. The lack of attention could also be because what is known about the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is dwarfed by the unknown: amid a maze of contradictory theories and studies, there's the plain old terrifying fact that not everything is known about its transmission. Scientists theorize that it can be sexually transmitted, but they think this happens fairly infrequently. Sometimes the virus moves fast, but usually it is glacially slow. Maybe it will kill; maybe its host will die of old age first.

I'm willing to bet my love beads that most of the public ignorance about this disease is spawned by fear and denial. And that duo feeds on what researchers know for sure: hepatitis C is a blood-borne disease, most often spread (in this country, at least) by intravenous drug use. I have what medical sociologists term a "sin" disease. Like AIDS in this century or leprosy in previous ones, just the phrase "hepatitis C" can telegraph a catalog of stigmas about its host. Junkie. Sinner.

Before the nonjunkies and righteous start feeling too relieved about their distance from this disease, there are a couple of things worth knowing. First off, it is not only needle users who contract hepatitis C. My priest friend Father Bill Rainford never darkened the doors of drug rehab, but he did have a heart transplant 14 years ago that also gave him hepatitis C through the blood transfusion. Before scientists had perfected the test that would screen blood donors for HCV in 1992, the chances of contracting hepatitis C through blood transfusions were as high as one in 10. However, Uncle Sam did not exactly rush out to let those folks know who they might be.

Although the government knew by 1990 that more than 300,000 people received HCV-tainted blood, the Food and Drug Administration was still debating until last year whether to tell those 300,000 that they had a potentially deadly disease. In 1998, blood banks began the laborious process of tracing back through their records. Then there are others diagnosed with hepatitis C who have a kind of Immaculate Infection: they swear they never picked up a needle, never had a blood transfusion, never worked in the health field (where they might have been subjected to accidental needle sticks) and never had promiscuous sex. Those folks fit in another Bermuda Triangle of this disease that epidemiologists have identified--the approximately 10 percent to 40 percent with no known vectors of transmission.

This has left a lot of people with understandable anxiety, and has left the CDC theorizing that the virus could have traveled through a rolled-up dollar bill used when snorting cocaine, from homemade tattoos and piercings, even through the use of shared razors or toothbrushes.

(To read the full article, click here.)

Hotlining

An intrepid reporter does hard time in the telepsychic trenches

By Andrea Perkins

For weeks the newspaper ads had been catching my eye: "Psychic Readers Network--Work at Home--No experience necessary." If no experience was necessary, then anyone could be a telephone psychic, I figured--even me. I was determined to try. I had seen the late-night television commercials that portrayed psychics gleaning the innermost secrets of amazed callers. But before I took the plunge, I decided to do a little homework.

The "Psychic consulting and healing services" section in the Santa Cruz County phone book boasts about 40 psychic hotline numbers. Skimming over the selection, I was tempted by Brigitte Nielsen's Witches of Salem, but finally settled on LaToya Jackson's hotline, since it was one of the more affordable, at only $3.99 a minute.

LaToya herself answered. "Find out what world leaders and celebrities have known for years!" her recorded voice said. "Now with just a phone call, you can have your own personal psychic, like I do." After wading through two minutes of menus, my own personal psychic came on the line. She said her name was Patrish. I thought Patrish was a good name for a psychic.

"What's your birthday?" Patrish asked gruffly.

Though I had decided to reveal nothing about myself in order to test her abilities, I answered Patrish's question.

"Oh! A fiery little Aries," she cackled. This cackle of hers was the only thing that seemed somewhat mystical about Patrish. Ten minutes and $40 later, Patrish had told me that she saw only wonderful things in my future, like money and love.

The job seemed like a snap. "I can do this," I thought.

I dialed the number in the Psychic Readers Network ad, deciding I wouldn't even pretend to be psychic. A woman (whom we will call Muriel) answered. After confirming that I could read and speak English fluently, she hired me.

"The goal is to reach an average of 20 minutes per call," she explained. "I have a 23-minute average. You really have to get that 20-minute average by your second night, because they don't keep readers who can't make the average."

It was easy to see how she got her 23-minute average. Muriel made an art out of slowly repeating things in slightly slurred variations.

"You have to be good enough to keep them on the line for a long time," said Muriel over the escalating TV noise in the background. "You're half psychic, half salesperson, selling minutes, selling yourself."

I asked her what exactly she meant by "psychic."

"You don't have to be clairvoyant or anything," she answered. All I needed to do was get a deck of Tarot cards, label them and follow the script she'd be faxing to me. "And ask them questions. You're like a counselor."

Counselor, salesperson, psychic? I was confused.

"Listen," she said, impatient with my questions. "There isn't really any training. Be aggressive. As long as they hear confidence in your voice, you're OK. Mostly they're calling because they're depressed and need a friend."

(To read the full article, click here.)

They Dream of Genes

When a biotech mogul wanted to lock up the secrets of the human genome, UCSC researchers Jim Kent and David Haussler made sure the code of life ended up in the public domain

By Sarah Phelan

With his green felt hat tugged down over wispy black hair, and his thick black beard, Jim Kent looks like a woodcutter who has just hacked a path through a forest a whisker ahead of a band of treasure-seeking dwarves. In a way he has. Only Kent's forest consisted of 400,000 pieces of data, and those "dwarves" were employees of biotech giant Celera Genomics. As for the treasure that both Kent and Celera sought, it was a document of unparalleled worth--the first rough draft of the complete human genome.

The human genome is best compared to a very long yet very compressed book--a biological Zip drive, if you wil--tucked inside the nucleus of each of the 100 trillion cells of our bodies. Organized into 23 chapters, one for each chromosome, each genome contains encoded instructions that help shape appearance, intelligence, health and behavior. No single human genome is the definitive edition of our book of life. Yet each version contains a how-to-manual for putting together a human being.

Little wonder, then, that the public and private sectors ended up competing to be the first to put together this priceless document. It was a high-stakes race with access to--and control of--the knowledge contained in our genetic blueprint at stake. More surprising was that Kent, a graduate student at UCSC, became the unlikely hero of this sprint.

The human genome project had first been envisioned 10 years earlier in Santa Cruz by former UCSC chancellor Robert S. Sinsheimer. At first, biologists had resisted the idea. Mapping the human genome was the biological equivalent of putting a man on the moon, and some feared that its cost--an estimated $3 billion--would suck dry the well of microbiological research funds. But the vision prevailed, and by 1990, the Human Genome Project was up and plodding, financed by the U.S. National Institute of Health and England's philanthropic Wellcome Trust.

More than a thousand scientists in the United States and England, as well as in France, Germany, China and Japan, toiled away using slow but methodical research techniques, and by 1998 they had mapped 90 percent of our genetic blueprint for life.

And that's when a privately launched bombshell hit.

In May 1998, Dr. Craig Venter, a brilliant and controversial scientist, announced he was forming a company (which would later become Celera) with the objective of sequencing the human genome first--and patenting the results.

While working at the National Institute of Health, Venter had been part of the first mass patenting of genes (which had, scandalously enough, been undertaken by the U.S. government itself). And now here he was, heading a commercial operation with massive sequencing capabilities, and threatening to snatch the treasure and lock it up in patents. If he succeeded, the fruits of years of research could be inaccessible for years, except to those willing and able to pay a hefty price.

In response to this threat, more money was pumped into the Human Genome Project, and a new deadline was set. Then in the winter of 1999, Eric Lander, director of the Genome Center at MIT's Whitehead Institute, asked Dr. David Haussler, a professor of computer science at UCSC and a leader in the field of bioinformatics, for help analyzing the project's data. Haussler took a look and said he'd need to assemble the data first, though he wasn't sure how. By spring 2000, he was still looking for the solution. Enter Kent.

A former computer animation programmer, Kent, 41, had returned to UCSC--where he had earned two degrees in mathematics more than a decade earlier--this time to study biology. As part of his graduate research, he analyzed the DNA of the lab worm C. elegans. And now it was May 2000, and he had just passed his Ph.D. qualifying exam.

Seeing that Haussler, a senior colleague with whom Kent had already collaborated, was still working on sequencing the Human Genome Project data, Kent made Haussler an offer neither of them would ever forget: Maybe he could modify his worm-analysis program for human DNA?

The offer pitched Kent into the forefront of the race with Celera. Nine months later, sitting in Haussler's office in front of a white board scrawled full of probability algorithms, Kent confesses that he was surprised at the significance his role in that race assumed.

"I thought I'd be one of thousands of researchers figuring out how you go from a genome to a human," Kent recalls, "but it turned out we needed this basic assembly first. I was at the right place at the right time with the right abilities and a little bit of luck."

What Kent calls luck, the rest of us would call genius. Working 80-hour weeks in a converted garage behind his Santa Cruz bungalow, Kent (aided and abetted by 100 Pentium 111 processors) designed and wrote in one month flat a computer program called GigAssembler. which organized the project's data into a coherent sequence using what Kent terms "a greedy algorithm." GigAssembler enabled Haussler, Kent and a team of UCSC researchers to analyze the Human Genome Project's data and put together a working draft of the genome's sequence.

On June 22, 2000, they made history as they witnessed the human genome's first assembly--an event Kent likens to the Wright brothers' first flight.

"People were working on that project, too, all over the world, and it was never 100 percent clear who actually flew first," he says, referring to the fact that their version of the genome, while less complete, was assembled a few days earlier than Celera's.

Recalling that moment, the ever-youthful-looking Haussler (who is in his late 40s) leans his lanky frame back in his chair and smiles. "Watching all those A's, T's, G's and C's came flying across the screen at the first assembly was the personal thrill of my career," he says. "To see it all come together here in Santa Cruz was amazing. That's the day we flew."

(To read the full article, click here.)

Rocking's Shocking

Nashville Pussy and a slew of morally suspect bands lead the newest wave of shock rock

By Mike Connor & Steve Palopoli

When it comes to the sleaziest, trashiest, most extreme end of the rock & roll spectrum, sometimes the truth hurts. And Nashville Pussy frontman Blaine Cartwright is more than willing to spread the pain around, judging from what he has to say about his band's new album Say Something Nasty: "It's our best one yet, and we're gonna shove it up America's ass!"

Jaded rock fans, however, are not so easily convinced. "It's all been done before," they'll say, sphincters still smarting from the last band that shoved its new album up their ass. And it's hard to disagree with them, just running through the catalog of shock-rock acts that have been sticking it to the American obsession with "family values" over the years: the pioneering freak shows of Alice Cooper, the masochistic onslaughts of Iggy Pop and the Germs' Darby Crash, the brutality of the Mentors, the horny sleaze of the Cramps.

And then there are the legends that, regardless of their validity, still teased and taunted our imaginations. Who cares if Ozzy never really refused to start a show until the puppies he'd passed out into the crowd were returned lifeless to the stage? Good for the puppies. And never mind that Gene Simmons never sliced his frenum, thus enabling him to seal an envelope at arm's length. Even if he didn't do it, surely there are one or two hundred diehard KISS fans out there that did.

Point is, we've been entertained, challenged, left speechless and probably hopelessly scarred by these rock antics, and bands like Nashville Pussy, who bring their an all-out psychobilly raunchfest to the Catalyst Friday, are carrying on the trash-rock tradition.

"The name comes from an intro to a Ted Nugent song," says Cartwright. "Ted said, 'I dedicate this song to all the Nashville pussy out there.' We were playing that song at the time, we had two women in the band and we lived in Nashville, so it just seemed to fit."

Husband and wife Cartwright (lead vocals, guitar) and Ruyter Suys (lead guitar) front the four-piece band, with Jeremy Thompson (drums) and Katie Lynn Campbell (bass) backing them up. Their debut album Let Them Eat Pussy was nominated for a Grammy for Best Metal Performance in 1998, which they lost to Metallica.

Cartwright still hopes to win a Grammy, but you wouldn't guess from his songwriting. Titles like "Keep on Fuckin'," "Down at the Jack Shack," and "I'm Going to Hitchhike Down to Cincinnati and Kick the Shit Out of Your Drunk Daddy" would make for an interesting award presentation, though.

The band's live show is an aggressive, turbo-charged, sexed-up free-for-all. It's stripped down to the bare essentials of shock rock: skin, sweat, nasty words and hard f'n' rock. But what would NP be doing if they had an unlimited budget to spend on stage gimmicks? Off the cuff, Cartwright says, "I don't know, maybe have thousand-foot dildo cannons shooting out vanilla ice cream into the crowd, I'm not really sure. I don't think it's gonna happen any time soon though."

What's amazing is that the brave new world of shock-rock has already gone far beyond Cartwright's dildo dreams.

(To read the full article, click here.)

Watching Baghdad Burn

Keeping up with the war via MSNBC

By James D. Houston

It is the first day of spring, 2003, and Baghdad is burning. The Defense Department calls it "Shock and Awe." You deliver so many bombs, stir up so much flame and mayhem, the leaders of the other side realize there's nothing else to do but quit. That is the operational theory. So here they come, 320 cruise missiles dropped through the night sky into a stretch of six kilometers along the Tigris River. And right there next to the spectacle on the screen, just underneath the billowing explosions, the smoke and the fire, the Dow Jones Industrial Averages are ticking away, steadily climbing as the devastation spreads.

This is the pre-emptive strike Kofi Annan and numerous other leaders around the world say is a violation of international law. This is the military invasion of a country that has yet to do anything to us. Though the polls say nearly half the people in the U.S. believe Saddam Hussein was behind the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center, no one has produced any evidence to support that belief. Our own CIA refutes it. There is no question that Saddam has been a brutal dictator (a fact that didn't bother us until he crossed the wrong border; until 1991 he was "our" dictator). No question that he is a deceptive scoundrel who has ruled by fear and ruthless intimidation. But what kind of solution is this? The most expensive and sophisticated military machine ever assembled on the planet Earth is being aimed a country slightly larger than California, and where half the population is under 15 years of age. Whose brutality is being revealed here today? Whose weapons of mass destruction are on display?

And why--as the companion track to these hellish scenes--do the Dow Jones averages continue to click along, down there in the lower right-hand corner of the screen?

While it's near midnight in Baghdad, it's midday on Friday here in the U.S., so the market is still open. But on a day like this, given what we're watching, given the many frightful implications of these flames rising from an Arab city of some 5 million people, I can think of several other types of data that the network news might offer to viewers as a running sidebar of relevant information. Weather forecasts from the neighboring regions of the Middle East could be very handy, or the ongoing numbers of casualties, as they occur--civilian as well as military, Iraqi as well as British and American. Or the sites of protests being mounted around the world, in Rome and Cairo and Beirut and London and Jakarta and San Francisco, with a running scroll that estimates the numbers of protestors globally at any given moment, the numbers of arrests, the numbers of police in riot gear who have been called away from other duties to deal with the surging multitudes; or some names and numbers for agencies one might contact if you wanted to do something on behalf of the people whose city is being bombed.

But numbers like these will appear infrequently and be less specific. We're not supposed to dwell on them too long. The screen tells us that, of all the numbers hovering around this wreckage, the ones we want to watch first are found in the moment-to-moment tracking of the Dow. And there is no great mystery about why.

Take those 320 cruise missiles. They will have to be replaced. At $1 million each, that's a $320 million contract for Raytheon right there in the first night's bombing. Consider the destruction done by those missiles, and the buildings, roads and sewer lines that will have to be restored. In the first big Wall Street rally after President Bush announced that Saddam had 48 hours to abdicate, one of the fastest-gaining stocks was Caterpillar, whose bulldozers and backhoes are sure to be in great demand.

Halliburton is already on the ground in Kuwait, in Turkey and in Afghanistan, via its engineering subsidiary Brown and Root. In November 2001, they secured a 10-year megadeal with the Pentagon to provide logistic support to military operations, for a profit, anywhere in the world.

Our bombs blacken the sky over Baghdad, while in the corner of the screen the numbers keep rolling, like lemons and cherries turning on their rollers in a slot machine. These two tracks play together, charting the progress of an infamous day: the relentless rain of weaponry, the billowing smoke, the fires reflected in the waters of the Tigris, the Shock and the Awe, side by side with the NASDAQ, the S&P 500. Somewhere offscreen the casualty rate is already beginning its climb, but we don't see that yet. The screen reminds us to keep our eyes on the fortunes of the Dow, up 235 points when the market closes, to cap the biggest one-week gain in 20 years.

(To read the full article, click here.)

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

For more information about Santa Cruz, visit santacruz.com.

![]()

Leap Year: 10-year-old Alex Benko is the poster boy for our 10th anniversary celebration. Like us, the boy just cannot stay still.

Sept. 14, 1995

March 7, 1996

Stun of Sam: For Richard von Busack's 1997 story on Quentin Tarantino's 'Jackie Brown,' he got in the thick of a debate on race politics and weathered Samuel L. Jackson's famous withering stare.

We Kid!: Our 1998 April Fool's Day story about the imaginary drug 'Akima' (illustrated with this photo of it supposedly being brewed up) reportedly had some readers chewing the pages of Metro Santa Cruz.

Dec. 2, 1999

Dec. 6, 2000

April 18, 2001

July 10, 2002

April 2, 2003

From the May 5-12, 2004 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.