![[MetroActive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Santa Cruz Week | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

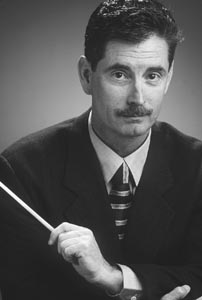

Slope Intercept: Conductor John Larry Granger leads the Santa Cruz County Symphony along a steep journey to the top of Mahler's Symphony

no. 2 Saturday at the Civic.

Granger's Great Mountain

Conductor John Larry Granger for the Santa Cruz County Symphony's season centerpiece takes on the Mount Everest of orchestral music

By Bruce Willey

WRITING ABOUT Mahler's second symphony--a piece I truly love--is harder than I thought. I think I could adequately write about the Pixies or the Minutemen--or even Mahler's Fifth. I really could. But Mahler's Second? Damn. It's been in my life for 15 years, and it continues to haunt and awe me.

So that's why, on a drizzly San Francisco morning exactly two weeks before John Larry Granger takes the podium Saturday at the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium to raise the baton and start the first daunting bars of Mahler's Second Symphony, I think that Granger wears whatever worry he has about delivering the symphonic equivalent of an expedition up Mount Everest with astounding grace. He has spent a year memorizing the piece one page at a time and has found a very close connection to all 209 pages of it--a connection to Mahler himself, too--and he seems very composed.

"If you can gain your own interpretation from your own life, then I think that's where the most truth comes from--and that's why the performance can be the most genuine," Granger says. "This is not a piece you can conduct going through the motions. It can't happen that way. You have to find things in it. Indeed there are plenty of big things to find in this piece. In a letter regarding Symphony no. 2 Mahler asked his friend, Max Marrschalk, 'Why have you lived? Why have you suffered? Is all this merely a great, horrible jest?' We must resolve these questions somehow or other if we are to continue living--nay, if we are only to continue dying. Once this call has resounded in anybody's life, he must give an answer, and that answer I give in the last movement."

These questions that Mahler asks can sometime seem, at least on the surface, a little adolescent--certainly in comparison to life's immediate and vexing problems. But he begs us to look beyond seemingly trivial questions up into a starry night, out at the grand expanse of ocean, to the mountains, and to feel, as a result, incredibly small. At the same time, Mahler with his second symphony asks us to feel consequential large in the grand expanse of things. Such great works of music succeed simply because words and even actions fail to enunciate the very business of being human.

A telling example: Ken Mattingly in 1969, after dropping his fellow astronauts on the surface, began a lonely circling rendezvous with the dark side of the Moon. Perhaps to make the isolated journey bearable, he listened to Berlioz and Mahler. What selections could possibly have been more apt as he stared out at the universe from a porthole shaded from the sun? An Irish jig? Will Smith?

It's a work that demands that listeners search for meaning in their own lives.

"We all have something in our lives, someone we know," Granger says. "This is about anybody's life and about all the question we all have ultimately. Sometimes there are questions we don't like to deal with. From the first time I heard this piece, I knew there was something very special about it." (Granger's father suffered from multiple sclerosis for 30 years and recently passed away.)

EVEN MAHLER SEEMED to know the second symphony was special after the first rehearsals in 1895. "The whole thing sounds as though it came to us from another world," he wrote. "I think there is no one who can resist it." Unfortunately his optimism and timing were wrong. He gave part of the symphony's premiere in Berlin without a completed final last movement to an audience of hostile critics and music students. The critics hated it. But thanks to Mahler's fortitude and stubbornness, he continued to work on it. Given the exceptionally long time that it took to complete (Mahler started it when he was 27 and finished at 34), the lack of encouragement from his mentor and the difficulty of mounting such a large orchestra that his works required, it is a wonder it was ever brought to the public in the first place.

Granger shares the same sentiment about the difficulties of delivering such a colossal work to the public. The orchestra, the choir, the symphony board, the community, all have to make a huge commitment, he says. "I asked myself, what is the piece that would be the Sound of the Century [title of the Santa Cruz County Symphony's current season]. But it was also a way of giving the orchestra a major challenge, of making a statement about how far the orchestra has come. This orchestra has always risen to the challenge, and they've really made a commitment to this piece. However, it is also a matter of physical stamina for them. Doing a piece like this is like training for a marathon. You have to build it one step at a time. The kind of pressure we put on musicians is incredible."

Of course there are also more practical concerns like how to fund such a large orchestra and choir while still staying within the season's budget. "The reason it is not performed more often is the practicality. In terms of music it has gotten so expensive, and you really need a wonderful orchestra, like we have here, to play it. A production like this one is about two and a half times the cost of a normal concert. The question that Mahler had--is there life after death--well, the question for the Santa Cruz Symphony--is there life after Mahler?" Granger says with rambunctious laughter.

One of the biggest scores in symphonic music, Mahler's Symphony no. 2 is scored for soprano and alto soloist, large mixed chorus (about 130 people), four flutes, four piccolos, four oboes, two English horns, four clarinets, three bassoons, 10 horns, eight trumpets, four trombones, a tuba, two harps, percussion consisting of two sets of timpani, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tams, triangle, two snare drums, glockenspiel, three deep bells, Rute (twigs, as in schoolmaster's switch, played against the bass drum) and finally the strings--a full complement of violin, viola, cello and bass. Parts of the stage at the Civic will have to be dismantled to make room for the choir, while parts of the orchestra will have to play on the floor.

Ironically, Granger, 51, is the same age as Mahler was when he died--and, happily, in rosy health that makes him look a decade younger, certainly no comparison to pictures of Mahler's death mask. The inside of the conductor's house has an almost too calm feel for a conductor who can bring to life such a beautiful, noisy, lively piece of music as Mahler Two. But as we talk, I realize he can read the score and hear the music in his head, thus needing the quiet that the Asian paintings and soft earth-tone walls provide.

"For those of us in the orchestra, for those that are artists, there is always a part of us that we want to leave behind, something that will outlive us," he says. As he says it, the spring storm lifts and the view from Granger's house, previously obscured by low clouds and showers, is magnificent. The 280 freeway, Cesar Chavez Boulevard and the bay all soak in the first sunlight of the day. Without getting too harmonic convergence or lost-boy-from-Santa Cruz about it, I think the view is akin to the airy "Wunderhorn" movement in Symphony no. 2, the movement that borrows from Austrian folk dances. Granger's telephone rings, and that's it for the image. His good neighbor has called to say the headlights on my truck are on.

"Very much like Beethoven and Brahms, there's a sense of the land," Granger says, looking back down at his worn Mahler score after I return. "It's not coincidental that the kind of writing Mahler did comes from the fact that he was such a wonderful conductor. Because many of his ideas, not only the concepts, come from other composers. He paints an incredible landscape with this kind of vastness filled with meaning."

MAHLER'S TRUE recognition as a composer came when he conducted the complete Symphony no. 2 in C Minor on Dec. 13, 1895 in Berlin. This time he gained funds from wealthy Hamburg patrons and filled the concert hall by giving away free tickets. On the night of the concert, he had such a fierce headache that he left the podium just after the sustain of the last note, notes that were wholly overshadowed by a deafening applause. Many in the audience wept and fell over themselves. Symphony no. 2 was indeed the beginning of Mahler's career as a composer.

"I know it is going to be a meaningful experience. The only thing I'm worried about is turning people way. Usually we repeat a program, but because of the cost and the facilities we are only going to do this once," Granger says, showing me to the door. He waits to make sure my truck starts, then waves goodbye.

At the bottom of his street I fish around the messy cab and find my familiar ragged unmarked tape, Bruno Walter conducting Mahler Two, and set it aside until I am heading south on Highway 1. I'll wait to put it on until the whole privacy of the ocean opens up out my right window, green hills and Brussels sprouts on the left. Then, in the privacy of a two-lane road, I'll pretend to sing with the choir, air conduct the parts I know well, weep freely with one hand on the wheel in the tender "Urlicht" ("Primal Light") movement. Mahler will be mine own. Until then, the noisy traffic of 280 and the truck's relentless squeaky shocks pound the way home.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Paul Schraub

Paul Schraub

Choral Master: For Saturday's Mahler

Symphony no. 2 concert, Cheryl Anderson leads a 130-member chorus that's even bigger than the orchestra.

Choral Master: For Saturday's Mahler

Symphony no. 2 concert, Cheryl Anderson leads a 130-member chorus that's even bigger than the orchestra.

Perhaps because this piece has so many musicians Mahler wrote offstage parts for some of the horns, giving the third movement the feeling of a crier in the wilderness. Nevertheless, even without the symphonic hyperbole that Mahler is also known for (Symphony of a Thousand a case in point), his incredibly light, delicate movements mirroring life's more tranquil and profoundly moving moments only coalesce completely with moments of grandeur and bombastity, and they're perfect examples of why symphonic music should be heard live to be heard. Modern sound recordists, Granger says, have yet to invent a way to capture the symphonic sound. "They have to make choices in terms of how much to bring out the strings or the chorus and so forth. There is no way they can do that without distorting something."

From the May 3-10, 2000 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.