![[MetroActive Travel]](/gifs/travel468.gif)

![[MetroActive Travel]](/gifs/travel468.gif)

[ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Mood Indigo

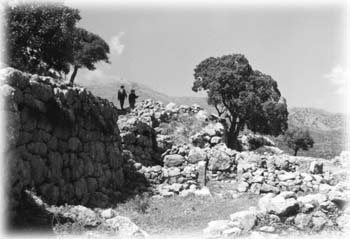

Rock Stars: The seventh-century B.C. walls of the ancient hill town of Lato still overlook the bay of Agios Nikolaus.

Minotaurs, moonshine and the Mediterranean blend together in a traveler's tale scented with the wild mountain herbs of Crete

By Christina Waters

ON A HIGH HILLSIDE overlooking the ancient bay of Agios Nikolaos, red poppies push their way through rock walls crisscrossing the slopes. These rocks--still arranged into houses, public squares, sacred chambers--are what remain of the once-mighty Cretan city of Lato. Snow-covered peaks loom to the south. In the distance the Mediterranean shimmers electric blue. Lato was already 400 years old by the time Socrates was born.

Let that sink in for a minute.

Great layers of time hang gently on the shoulders of this Mediterranean island, whose harsh limestone landscape is everywhere softened by lush agriculture and passionate attitudes. Straddling the intersection of Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Crete has been a magnet for travelers since the Neolithic era and a conquering field for waves of Mycenean, Roman, Venetian and Turk invaders.

Minoan rulers, ensconced in gorgeously decorated palaces, played out sensuous soap operas that spawned the lusty gods of the Greeks. Their priestesses were wielding snakes and taking names 3500 years ago, a period when northern Europeans were still wondering what lay just beyond the cave door.

If not exactly Theseus, I nonetheless succumbed to the spell of this island elixir--a cocktail that combines the wild scent of oregano, the suppleness of olive oil and a hint of goddesses who still haunt the ancient groves. Drunk deeply enough, Crete could probably bestow eternal life. Sampled briefly, it leaves a permanent emotional tattoo.

Road Show

ALL CRETAN MEN SMOKE. All Cretan men are handsome (deeply, darkly handsome). All Cretan women really run the show. And this is as true in rambunctiously tacky Heraklion--with a population of 140,000, the largest center of arts and commerce on the island--as it is in the foothill villages where matriarchs gossip over pine-scented stoves.

In early April, with the real tourist season still three weeks away, Crete obliges with a sudden rush of spring color. Hyacinths, anemones and lupines outline roadsides and farmlands with glimmers of pink, while swaths of mustard and oxalis carpet the olive groves with chartreuse. Almond trees blossom shamelessly, and even the vineyards hugging the chalky cliffs fling fresh greenery out into the afternoon warmth. Poised at the brink of summer, the island is as green as it gets--and the effect is enchanting.

Personal magnetism aside, Crete is only 150 miles long and anywhere from eight to 40 miles wide. Its major ports once faced Africa, where the action was two millennia ago. Today they line the northern, Eurotropic coast. To the west, the island is a warren of fabulous gorges and grottos, crowned by the lovely harbor town of Chania.

The eastern edge is a series of more of less organized tourist boomtowns--Crete is Germany's Mexico and, from May until November, is filled with as much bratwurst as Lufthansa can supply to the steady stream of Munich professionals determined to get spectacularly sunburned. In the east are also remnants of pre-Christian Greek cities, like Lato, as well as beautiful Byzantine chapels, among them Kera, whose glowing 13th-century frescoes still convey the passion of their artists' vision.

Since our time is short, we do what all visitors invariably do here and plan a pilgrimage to Crete's ancient glories. Starting from our well-appointed base at the Apollonia Beach Hotel just east of Heraklion, we'll follow the road that literally bisects the island to the Minoan temple excavations at nearby Knossos and further south at Phaestos.

Crete is as much about eating, drinking and dancing, we quickly discover, as it is about ancient civilization and naughty mythology. The night before we set off for the 4,000-year-old remains of Phaestos, our dinner at the hotel is followed by a sudden outbreak of costumed dancers. Jaded travelers are tempted to wink at such folkloric displays. But in this case, we are targets of a precise seduction.

Graceful, swirling and blatantly sexual, the men dominate the dancing--hands held high, moving with edgy grace, a gleam in each eye. But the real force of Cretan dance begins when the audience begins to join in. Sure, it's like Zorba. That's why we all responded to Zorba, whose creator's home lies a few kilometers from this hotel. With or without a few glasses of ouzo, it is impossible to listen to the hypnotic rhythms of Greek music and stay seated.

From a tight central core of four, maybe six dancers, arms around each other, moving around and around, more of us join in, opening up the spiral into more layers. A large stack of dishes--outtakes from the kitchen--lies near the stage. These are for the dancers to break when the spirit moves them. I pick one up and smash it on the floor, my brain chemically altered and unrepentant. My fellow dancers approve, and do likewise. In this moment we are psychically linked in a ritual whose origins we will detect in the sacred baths and stone cisterns of Phaestos.

Secret Weapon

THE CENTRAL VALLEY of Mesará, whose velvety green terraces and curvaceous hillsides are punctuated by snowy white cruciform chapels and great scraggly bouquets of goats, is watched over by a snowy mountain range dominated by 8,000-foot Mount Psiloreitis, Crete's highest peak. Miniature white shrines pepper the roadsides, erected, we discover, by grateful drivers at the spot where they've narrowly escaped death by car crash. Makeshift oil lamps and the odd religious icon translated into pop plastic populate these tiny chapels du jour.

Devotion is genuine in this country, where each tiny village church--usually so packed with icons and candelabra that only three human worshippers can squeeze inside--are always open, the key left in the door. Why would anyone steal anything? In Crete, you not only know everyone in your village, you're probably related to everyone in your village.

And that's Crete's true secret weapon--a tangible sense of community, of living in fully functional extended families, young and old together--that takes away the breath of European and American visitors.

Mind you, it's not all warm and fuzzy. Like all emerging resorts, Crete has a love/hate relationship with its steady stream of fair-skinned visitors. The closer you get to the coast--and the plethora of tacky tourist shops that line voluptuous beach towns like Malia--the more that sweet-faced old man in the street is probably mocking you while appearing to offer you oranges fresh from his orchard. But as you travel away from the resort strips, into the more remote hill towns, where shops still line the steep, narrow streets--bursting with rich red textiles, intricate pottery and endless gold necklaces--things change. The old woman in black, sitting in the sun as if straight from central casting, is likely to be just what you want her to be--somebody's grandmother, warming herself, keeping an eye on the kids playing around the corner, happy to shake your hand. We take the twinkle in her eye for pleasure. But who knows what she's really thinking.

Maybe it's the crystal clarity of the light--and it would be so easy to romanticize a place with this much potency--but Crete is a land of magic realism. Every color is intensified, shadows turn to black velvet, sound is magnified, flavors devour the palate. Forty centuries ago, explains our expert guide, Lina Kogakis, olive oil was pressed into these stone basins.

We are gathered on the wind-swept site of Phaestos, home of Bronze Age fertility cults. We alternate our gaze between the very old plazas carved out of the hillside and the very fresh snow on the peak of Mt. Ida just beyond. Minoans knew a thing or two about location, we agree, stunned by the sheer antiquity of the paths we walk.

Next day at Knossos, where Kogakis again leads our minds through the labyrinth of King Minos, legendary son of Zeus and Europa, we get a better idea of what the Minoan golden age must have looked like to those bare-breasted bull dancers. The excavation of Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans includes reconstructions--complete with painted frescoes, columns, recreated rooms--all as imagined by the controversial archaeologist.

The astonishing treasures of Knossos, including the famous snake priestess figurines, are kept at the Archaeological Museum in Heraklion, where Kogakis is available for official tours. Her passion for Crete's heritage, her command of English and her inability to suffer fools make her commentary one of the high points of our week.

Food of the Gods: The village of Vori lays out a spread of traditional dishes--and 100-proof hospitality--at a town hall social.

When in Crete

FOR ALL ITS SPRING blossoms, punctuated by choruses of citrus, the land is defined by vineyards and dominated by olive trees. The vines here produce what will become golden raisins, dried in their sunny fields. We eat those raisins each morning at the hotel's gargantuan buffet, adding them, along with local almonds, to mounds of gooey, tangy yogurt and top it off with unctuous, thyme-scented honey.

The olive, whose oil permeates Cretan cuisine, is also the prevailing decor of the landscape. The soft, gray-green groves terrace every possible niche of this wild, rugged terrain. The trees support an edible underbrush foraged by goats and humans alike. Those gathered greens find their way into zesty salads of thyme, sage, arugula, mint, mustard, dandelion and nettles, as well as into the cooked greens called horta that are endlessly amplified--by village tradition and chef's whim--with grains, legumes, lemon and, of course, more olive oil.

If the olive dominates the texture of the countryside, oregano is the ubiquitous perfume of the cuisine. And while you can read any number of guidebooks about the priceless antiquities of Crete, few will tell you how to sample the real foods of the island.

Forget about restaurants with menus in English--forget about gyros.

One memorable taverna experience will illustrate.

Embolo--on Evans Street just inside the thick Venetian-built walls of Heraklion--is among the best of the typically Cretan hearths. A raised fireplace gives a smoky perfume to the room with a smoky perfume, where a dozen of us gather around a long corner table. In a ludicrous blend of tourist Greek, English and hand gestures, we ask that the house bring us whatever it feels we should have.

The ubiquitous rosé wine--so delicious with its burnt sherry flavor and so right with the rustic countryside flavors--fills small tumblers. Noisy toasts are raised across the table, and the dishes begin pouring from the kitchen. Food as bold and straightforward as the wine proceeds to charm us silly. Plates of barley rusks--like round bruschetta topped with juicy tomatoes, oregano and olive oil--join plates of tiny olives so intensely flavored as to border on the psychedelic.

We spoon skordalia, the Cretan aioli, onto braised bitter greens. Brought the minute they are ready, puffy omelets arrive filled with goat cheese, tomatoes and sage, and teamed with slices of roast potato. Eggplant, squash and black-eyed peas have been tossed with bits of egg and anchovy. Baby favas with lemon. Fat favas with tomatoes. Dolmas, tiny and exquisitely pungent. All are superbly and simply cooked. Salty lamb chops with medallions the size of a 10-drachma coin finish us off.

The renowned honey of Crete, filling big bowls, comes ready to crown puffy cheese pastries and wedges of soft fresh goat cheese. A dozen shot glasses are placed at the table, along with a glass pitcher of clear liquid. It is time for the throat-searing grappa called raki. Actually, on Crete, true hospitality dictates that it is always time for raki. Knowing better, we all still downshots of the national white lightning and, after paying a ridiculously small amount of money (roughly $20 per person) and shaking the proprietors' hands, we slip out into the night to watch the crescent moon and comet sail into the Mediterranean.

Life may not be long enough to recover from Crete.

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Christina Waters

Donna Paul

From the May 1-7, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.