![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro Santa Cruz | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Disabled by Law

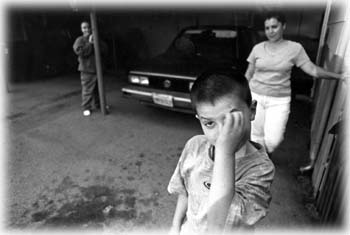

Speak No Evil: Ryan Jones couldn't find a place in the Santa Cruz school system, despite a law guaranteeing his right to a public education.

More than 20 years ago, Congress passed sweeping legislation to protect the civil rights of disabled children by guaranteeing them an education. California still hasn't gotten around to enforcing it.

By Kelly Luker

IT IS THE MIDDLE OF A SCHOOL DAY, but 9-year-old Ryan Jones is at home, showing his visitor a collection of Star Wars memorabilia. Unable to speak because of a stroke suffered at birth, the bright-eyed youngster points excitedly to miniatures of Darth Vader and R2D2 as his mother Karen smiles and looks on.

The tender scene belies the controversy around this mother and her disabled son. Ryan is not playing hooky--Karen Jones pulled her child out of school, disgusted with school officials' failure to give him what he needs to get an education. After two years, numerous meetings involving several attorneys and, finally, a formal civil rights complaint, it doesn't look like Ryan Jones will be back in school anytime soon.

The story behind Ryan's and Karen's fight can be traced back more than a decade before Ryan was born. A federal law known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was passed in 1975, requiring that children with special needs be taught alongside other school children "whenever possible" in the "least restrictive environment." It is these two phrases that have become a sticking point between Santa Cruz County educators and parents of disabled kids. These parents, including Karen Jones, have joined together to file a complaint with the Civil Rights Office at the U.S. Department of Education.

School officials say they do not have the money or resources to provide so-called special-needs kids with what they require to be able to learn in a regular classroom. They cite the oft-heard "unfunded mandate" complaint: although federal law demands that disabled and non-disabled children be integrated, the government has not put up the money to provide what children with disabilities need.

Some educators even argue that parents like Karen are in denial about their children's disabilities--that attending regular classrooms does not help these kids and unnecessarily burdens teachers and other students.

But Karen and the other parents simply state that Santa Cruz County educators do not comply with the law--and perhaps do not even understand it. They charge that the school district cares little about the rights of special-needs students, and makes little effort to inform parents of their rights.

A Mother's Hopes

AS RYAN PLAYS with various alphabet blocks while Nickelodeon's Blue's Clues blares in the background, Karen Jones recalls that her son started showing developmental problems when he was about 2 years old. Since then, he has been variously diagnosed as having borderline autism, moderate retardation and a language disorder. After his first year in a regular kindergarten class, Ryan was placed in a severely handicapped class at Westlake Elementary School. And that, says the mother, is when things went south.

Ryan had been toilet-trained and taught table manners, but lost all those skills in special ed. And he picked up a few new ones--such as screaming and acting out--within weeks of his new placement. He would come home soiled and bruised, then revert to eating with his hands.

"Handicapped classes feed ineptness," Karen says. She is joined by other parents who insist that kids learn by example. The parents concede that it may be easier for educators to group disabled children together, but they insist that that merely teaches the children how to be handicapped as adults.

"I have dreams for Ryan," Karen says, "and they don't include placing him in a home."

Karen says she wanted to see Ryan in his neighborhood school, which would require a one-to-one aide as well some communication equipment. She says she was met with resistance and excuses. In frustration, she quit her job as a medical assistant, then took Ryan out of school. A tutor now comes to their home for an hour every day, and Ryan visits a speech therapist once a week. A single mother with another child, Selina, 12, Karen has since gone on government assistance that will soon run out.

Not Giving Up

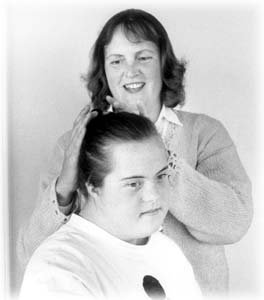

IT MIGHT BE POSSIBLE to write Karen Jones off as a determined but misguided mother if she didn't have so much company. Mary Lee Kinney tells a similar story. Kinney's 16-year-old daughter, Breandan, a child with Down's Syndrome, is now doing well as a freshman at Santa Cruz High School. Yet her educational career wasn't always so smooth.

The Kinneys say they decided when Breandan was very young not to treat her much differently than they treat their other five children. Things were OK through day-care and kindergarten.

"But then we got in the school system," Mary Lee Kinney says.

Kinney says the school system labeled her daughter "not educatable" and virtually ignored academic instruction. She recalls a teacher asking her why she wanted Breandan to read.

It was left to the Kinneys to hire tutors and purchase teaching materials in order to prove that Breandan could learn to read. Like Karen Jones, the Kinneys finally took their child out of school.

Mary Lee Kinney found out about Protection and Advocacy, Inc. (PAI), a statewide organization for the disabled, and ordered their legal handbook Special Education Rights and Responsibilities. And then she got angry.

"I thought, when my daughter wasn't getting anything, that she wasn't entitled," Kinney says. "Until I requested that booklet, I wasn't aware that my kid had any rights."

What Kinney wanted was an adequate academic program with at least partial inclusion in regular classes. Although its definition is simple, inclusion can be a complex problem. And it invariably costs money. The payoff, parents say, is a kid who learns to live in the real world of non-handicapped people.

If not, these children are virtually doomed to follow the path of handicapped kids before IDEA was passed: from "special" schools to group homes--the end of the line.

"I feel like I did when I was fighting for civil rights in the '60s," says Kinney, who now runs an environmental science firm. "Discrimination against people with disabilities is easier to hide. But our kids deserve the best possible."

Photo by Robert Scheer

Californians Don't Care

ALONG THE WAY, Kinney discovered other equally frustrated parents. She developed a complaint questionnaire that 16 families have filled out to date. Protection and Advocacy, Inc. has used this information to file its complaint with the feds on behalf of the families.

The group charges the Santa Cruz County Office of Education, the 10 school districts within the county and SELPA--the agency which oversees the special ed program for north Santa Cruz County--with a host of violations.

Oakland-based PAI attorney Nicole Larkin explains that the complaint "looks at systemic problems in Santa Cruz County."

"The County [Office of Education] places the kids in different school districts," Larkin says. "But districts, when they look at the kids, look at them as County kids--so they don't feel any responsibility to them."

"It seems with Karen, they just didn't understand the guidelines," Larkin says. "Ryan Jones was not diagnosed properly. He was not referred out of county to a professional with appropriate credentials, which was a gross disservice to him."

County and district school officials say they can't comment on the case because it's in litigation. But the county is clearly not the source of the problems. The same complaints are echoed throughout a state that, since the passage of 1978's Proposition 13, ranks well below the national average on what it spends to educate its children.

Ranked in the bottom 20 percent of the nation--41 out of 50 states--California allots $4,977 per student, compared to the national average of $6,098. California's concern for the education of its young is also reflected on how much of each resident's paycheck goes to schools. While Wyoming allots close to $60 out of each $1,000 earned, Californians cut loose with a miserly $34.

Meanwhile, the number of kids diagnosed as learning-disabled has tripled since 1976. Advocates say this is due to better diagnostic services. Children once labeled as troublemakers or "slow" may now be diagnosed with dyslexia, attention deficit disorder or, like Ryan, a range of subtly different learning disabilities.

Everyone involved agrees on one clear fact--there's not enough to go around. Not enough properly trained special-education teachers, not enough resources and not enough money.

Too bad, say parents and their attorneys: The law must still be followed.

"You can't discriminate against people with disabilities," Larkin says bluntly.

Spell Check

WITH FEDERAL, STATE, city and county jurisdictions all competing for--or avoiding--responsibility, these parents confront a confusing mishmash. It is supported by a latticework of acronyms--administrators talk about SELPA and IEPs and SHs and CHs, drowning the uninitiated in alphabet soup.

Joyce Bellinger, director of the Special Education Local Plan Area (SELPA), concedes that there is a communication problem.

"Jargon sets up a barrier," Bellinger says. New to SELPA, she has worked in the field of education for 22 years. Parents and advocates that have worked with her say they believe Bellinger is committed to making a dent in the unwieldy politics, and that she tries to work with the scarce resources that define the special ed system.

Bellinger also concedes that responsibility shifts like a "hot potato" between county and school district.

"Just like any agency, it doesn't run as smoothly as you want it to," she says.

But the problem is bigger than the bureaucracy, she says. When IDEA was passed, it was projected that about 10 percent of the school population would need it.

"But approximately 12 1/2 percent of our students are requiring special education," Bellinger says. "And they are more expensive. Parents may want a one-to-one aide. The school district will have to pay--and there's not enough money."

But Bellinger says the parents may need to adjust their thinking.

"I think there are parents in denial about what their kid can do," she says. "It's hard as an educator to walk a fine line, to not hurt parents' feelings, but be honest."

Karen Jones has made some headway. She has convinced school officials to change Ryan's designation from "severely handicapped" to "communication handicapped." That one word makes a difference in how--and if--her child will be educated.

"It's called advocating for your child, but we're not advocating," Jones says. "We're fighting."

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Robert Scheer

Special Education: Mary Lee Kinney pins up her daughter Breandan's hair before her dance class, which Breandan has been attending for eight years.

From the May 1-7, 1997 issue of Metro Santa Cruz

Copyright © 1997 Metro Publishing, Inc.