Mean Scenes And GoodFolks

Martin Scorsese takes viewers on 'A Personal Journey' through film history

By Rob Nelson

MARTIN SCORSESE'S Casino played like the director's ultimate confession of obsessive-compulsiveness. Stacking the odds against his tendency to win critical favor, he remade GoodFellas, but as a darker, more complicated, more resonant film.

So it's no wonder that in his newly released documentary, A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (on three videocassettes from Miramax Home Entertainment or on laser disc from the Criterion Collection), Scorsese issues high praise to veteran directors like John Ford and Raoul Walsh--directors who, throughout their careers, chose to redeploy familiar actors and plots in "endless, increasingly complex, sometimes perverse variations."

The difference between Ford's Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956), for example, mirrors that between a short story and an essay, a declaration and a rebuttal, a gifted artist and a mature one. Scorsese's point is that genre conventions don't confine the great filmmaker so much as help reveal where he stands, just as versions of (film) history inevitably reflect the tastes and politics of the teller.

Made as part of the British Film Institute's Century of Cinema series, this is indeed a personal trip through the U.S. canon, one in which 2001: A Space Odyssey represents the height of special effects, Cat People matters as much as Citizen Kane, and Hitchcock factors not at all. In a brisk 210 minutes, Scorsese (co-writing and -directing with Michael Henry Wilson) admits he can only scratch the surface and vows to avoid most everything post-1968, the year he released his own first feature. (A notable exception is made for Kubrick's Barry Lyndon.)

These parameters don't excuse every conspicuous absence--Dorothy Arzner, George Cukor and Oscar Micheaux are all MIA--but they do set the agenda: to render the personal in a historical light while giving even highly evolved buffs a fresh list of must-sees.

IN MORE WAYS than one, Scorsese's goal is a privilege; for instance, the auteur's industry juice enables Gregory Peck to stop by for a discussion of Duel in the Sun, the film Marty's mom took him to see at age 4. And at its most analytical, the documentary still invokes the director's own mythology. "There's no reprieve in film noir," Scorsese argues. "You just keep paying for your sins."

This isn't to say that Personal Journey is merely self-indulgent. Obviously, the man knows his movies. He links the crime film and the Western by tallying their preoccupations with violence, the law and the individual; and he likens '30s musicals to gangster films for sharing both manic energy and James Cagney.

Other references are more thickly intertextual, with The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)--Vincente Minnelli's film about filmmaking--becoming a hectic hub of allusions. To name a few: The Bad and the Beautiful's story of B-movie ingenuity paid homage to Cat People's no-cat style and was sequelized by Minnelli himself in Two Weeks in Another Town (1962), the latter film inspiring Scorsese to observe, in a distinctly Casino-like voice-over, that by the early '60s "the pioneers and showmen were gone, the moguls replaced by agents and executives."

Like Casino, Personal Journey expresses nostalgia for the precorporate days when rugged iconoclasts and "expatriate smugglers" ruled the roost. If this sounds like a Western motif, it's maybe no coincidence: Scorsese's sharpest writing in the documentary includes his ruminations on the horse operas of Ford, Anthony Mann and Clint Eastwood, suggesting that he may be ready to traverse his last uncharted genre.

The auteur's other chief obsession these days appears to be Kubrick, which is evident in the near-religious respect given to 2001 and Barry Lyndon ("one of the most profoundly emotional films I've ever seen," he says), but also in the fact that Scorsese's last two features have carried a strongly Kubrickian chill.

Of course, this buff's tastes are too catholic to hold just one idol. Scorsese's final clip is from Elia Kazan's immigrant epic America, America--which, like Kubrick's films but more subjectively, describes where we came from and where we're going.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

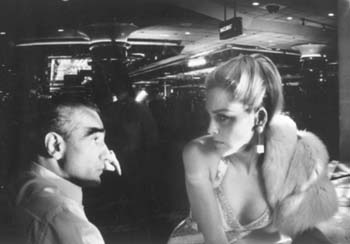

Nice Work If You Can Get It: Martin Scorsese directs Sharon Stone in a scene from 'Casino,' his nostalgic tribute to the moguls--of gambling and moviemaking.

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies can be ordered through Buena Vista Home Video by calling 800/986-5775.

From the April 30-May 6, 1998 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.

![[MetroActive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)